Who Cares What Happened to a Middle-Class Hijacker?

They took his store away from him, he took their plane away from them

June 1 1972 Jerry BledsoeThey took his store away from him, he took their plane away from them

June 1 1972 Jerry BledsoeThere was foreboding in the parting, although at the time Barbara von George didn’t know the reason for her uneasiness. She cried. She didn’t want him to go. But she was not the kind of wife to say don’t go. She would never do that. She placed total faith in her husband. He had always protected her and the children. She relied on him completely. She knew that he would do what he had to do.

Yet there was something about this trip, something different from the times he had had to leave before. She sensed it, but she didn’t mention it.

He had been rather vague about it, for one thing. But she had not pressed him on it. She never pressed. He had told her about it the week before when he brought home the latest bad news. She was sitting in the front room and he came in and stood by the radiator and looked out the window and said, “Now don’t get excited . . . I’m going to be arraigned for fraud.” She was surprised, of course. She couldn’t help but be. The whole thing was so much against his nature.

Heinrick von George had been out of work for nearly five months and hadn’t been able to find a job. He’d put his family on welfare, but he’d tried to keep them from finding out about it. He was a proud man who had always been a hard worker. He looked down on people who took government handouts. It had been nearly three months before his wife found out about the welfare payments. Their seven children still didn’t know. Now Barbara von George was learning even more. For her husband was telling her that all those months they had been getting the welfare money he had also been drawing unemployment checks. That is against the rules. And he had been found out. The welfare people had called him in for a hearing, from which he had just come. The payments had been cut off, and he was told that he would be indicted.

“But don’t worry,” he assured his wife. “It’s nothing. I’ll work. I’ll pay it back. Don’t worry.”

And she didn’t worry. She believed him. She always believed him. There had been hard times before and they had come through them together.

It was then that he told her about the trip.

“I made a call on the way home,” he said. “I’ve decided to take the job in New York.”

It was typical of him to try to counter the bad news with good that way. He had mentioned something about a job in New York before. But he hadn’t been specific about it. It was supposed to be with some drugstore chain, setting up and opening new stores, the same kind of job he had had before. But he didn’t tell her much about it, and she didn’t press him on it. She seldom questioned.

In the days following his confession, Ozzie—as his wife had always called him—seemed to relax somewhat. He became more like his old self, laughing and making wisecracks and playing with the kids. He had been worried, his wife knew, and that had worried her. It had been especially bad the past couple of months. She would come home at times to find him sitting on the radiator by the window, his glasses on a table, his head buried in his hand. He was a lively man who never sat around that way. She knew he was troubled, of course, but when she asked him about it, he would say, “No, no, it’s nothing. I was just thinking.”

He always tried to protect her from unpleasantness. But she knew, as a wife would, and she would caution the children (seven can create quite a ruckus at times) not to bother their father.

“Daddy’s upset because he can’t find a job,” she’d say. “Don’t disturb him.”

To be sure, Heinrick von George had reason to worry. Things had not been going well for him for some time. Trouble had begun after he had decided to go into business for himself in 1963. He left his job as a supermarket manager and opened a small wholesale cigarette and candy company in Peekskill, New York, his wife’s hometown. He tried to expand, adding route salesmen and absorbing a couple of cigar stores. But after only a couple of years the business went under, closed on court orders brought by creditors. Von George was deeply in debt, but more than that he was deeply frustrated and hurt by his failure. He was a man with big plans who liked to talk about them, and success was important to him.

After he lost the business, he got a job once again as a supermarket manager, hoping to pay off some of the bills and clear his name, he told his wife. But it didn’t work out. Instead of whittling down the bills, he seemed to keep accumulating them. Eventually, the family car was repossessed, and the bank foreclosed on the house. In the Summer of 1968 von George admitted defeat and declared bankruptcy.

In the meantime, he had taken a new job with a Rhode Island drugstore chain. He set up and opened new stores, mostly in Massachusetts. His family remained in Peekskill with his wife’s mother, and he came to be with them on weekends. The new job paid well and it looked as if things were going to be better.

In 1970, after the birth of his seventh child, von George moved his family to Massachusetts. They lived for a while in a rented house in Canton, a community south of Boston. Then von George bought a modest, two-story shingled house in a working-class neighborhood in nearby Brockton.

At the end of 1970, von George changed jobs again, going with a new drug company that offered him $50 a week more. He had changed jobs often in the past, whenever the opportunity came to make a few more bucks. This time it was a bad move.

The new company foundered three months later, and von George was out of work. Jobs were scarce then and he couldn’t find another right away. That was when he went on unemployment the first time. He was embarrassed about it, his wife knew, but there seemed to be no other choice. He was out of work for about three months when he decided he would try something new. He took a job with an insurance company and was sent to Nebraska to take a short course in insurance selling. He returned in July and went to work selling health and accident insurance, usually making his calls at night when people were more likely to be at home. He did very well the first month and seemed to like it.

But in August there was a crisis in the family. Eight-year-old Gary had to undergo open-heart surgery to correct a birth defect. The operation didn’t go well. The doctors couldn’t stop the bleeding. For five days the child lay near death. Once his heart stopped. Electrical shocks were used to get it started again, leaving burns on his chest and bald spots on his head. Von George and his wife spent every day at the hospital. Gary improved slowly. But after that von George seemed to lose interest in his new job. It wasn’t going well, and in September he lost it, and he didn’t tell his wife about it.

That was when he made the mistake of applying for welfare and unemployment payments simultaneously. Despite the fact that he was getting assistance from two sources, things grew worse. Bills piled up. The mortgage payments fell behind, three months, four months. The telephone company took out the phone. Each day von George dressed himself in suit and tie and went in search of work without success. And for the first time since his wife had known him, he began showing signs of depression. There was more troubling him than his wife knew. Things he had kept from her. A creditor from the days when he was in business, a man who claimed von George owed him $87,000, who for some reason von George had not included among his creditors when he filed bankruptcy, had hired a collection agency to trace him, and the agency had recently located him in Brockton. There were other things still, darker things in his past that he had successfully kept hidden for more than twenty years, things that might come out if he were indicted, things that would surely hurt his family. Heinrick von George had been living a deception for a long time, and it was about to catch up with him. He must have known that.

Three days after he told his wife about the coming indictment and the job in New York, von George went into Boston, to an employment agency, he told his wife. It was Friday. When he returned, he had twelve dollars. Traveling money, he said. And the man at the agency had told him to get a haircut. He was to leave for New York on Monday to see about the new job.

He gave the money to his wife, and she tried to get him to take some of it and get his hair cut. But he wouldn’t. His hair was getting a little long in the back, but he didn’t want to spend the money because he wouldn’t have any to leave with her when he left. All weekend, though, she kept after him.

“Ozzie, get your hair cut. You’re going for a new job. You gotta.”

But he wouldn’t. And he wouldn’t let her pack a bag either. He said he wouldn’t need anything, he’d only be gone a few days. This was strange to his wife, because he was a meticulous man who bathed and changed clothes every day and was much concerned about his appearance. He’d never left before without taking a bag, no matter how short the trip. This bothered his wife.

“Ozzie, pack a bag,” she kept saying. But he said no.

Von George didn’t leave on Monday, as he had planned. Instead, he went downtown to pick up the surplus food his family had been receiving. He seemed to want to linger at home with his family, his wife thought, and because of the uneasy feelings she had been having, this secretly pleased her.

But the next morning he got ready to leave. It was January 25. He left a little after nine. He said he’d be back by the weekend, and once again he told his wife not to worry, that everything would be all right. He’d get the job. They’d put the house up for sale, and when school was out, they’d move back home, someplace around Peekskill.

He wanted to know if it would be all right to call one of the neighbors while he was gone to let her know how things were going. She told him to call her mother in Peekskill instead, and then she would call her mother to get or leave messages.

She tried again to get him to take a bag, but he said he wouldn’t need it. He took only one of the twelve dollars, just enough for bus fare into Boston. He would get a ticket there, he said, and more expense money.

She began to cry. “Don’t go,” she wanted to say, but of course she didn’t. Her husband kissed her, and it was different from all the good-bye kisses before. He kissed her hard and held her face. He never did that.

It had been raining earlier, and she tried to get him to take an umbrella. He wouldn’t.

He left the little front porch and walked across the narrow yard to the street, and as he did his tie fell off. It was one of those clip-on kinds, a blue-and-pink one. She had picked it out to go with the pink shirt and grey suit he wore. He didn’t notice it fall and she called to him from the doorway.

He stopped, but the wind was blowing hard and he couldn’t hear what she said (he was hard of hearing anyway; that was why he talked so loud), and he started back toward the porch. She pointed to the tie lying on the ground and he laughed and picked it up and put it back on and started off down the street. She went back into the front room to the bay windows and watched him go. She was thinking how good-looking he was. She’d always thought he was good-looking. Even though he’d gained a lot of weight (he was five foot seven and weighed 235), he looked the same to her as he had when they’d met nineteen years ago.

A couple of houses down the street, he turned and saw her watching from the window, and dramatically he threw her a kiss. It made her smile and she gave him the peace sign. They fooled around that way all the time. Then he turned and was gone. She was never to see him alive again. Her life was about to be jolted by a series of shocks that were so unreal as to be unbelievable. But they were real and she and the children would have to learn to live with that reality.

Later, she would not be able to find any evidence that her husband had ever been offered a job in New York. And she would go over all the details of that parting, as she had done in her mind so many times before, and she would see then the reasons for her foreboding on that day, all the signs and the little things she should have realized before, and she would break down, sobbing quietly, saying, “I should’ve known . . . I should’ve known. But who would know that?”

In the late afternoon of January 26, a Wednesday, a short, stout man boarded Mohawk Airlines flight 452 at the Albany County Airport in New York. He was not a man to attract particular notice. He was dressed in suit and topcoat and he carried a small bundle. He looked not unlike any other middle-aged businessman. He wore dark, wide-rimmed glasses and his hair, which was combed straight back, was a little long. He had a one-way ticket for LaGuardia Airport in New York, for which he had paid $22. The ticket bore the name Grate. He took a seat in the last row. The plane, a Fairchild 227 twin-engine propjet, left Albany at five past six. There were forty-three passengers on board.

Forty minutes later, as the plane neared White Plains in Westchester County, the man left his seat and approached the stewardess, who was standing in the rear of the cabin. He quietly thrust a pistol against her side and told her that she was a hostage. He was hijacking the plane. He wanted it to land at the Westchester County Airport near White Plains.

The stewardess, Eileen McAllister, a thin thirty-five-year-old New York City resident with short blonde hair, pushed the button on the plane’s intercom system and quietly told the pilot what was happening.

The pilot was Karl Rieth, a tall, thirty-seven-year-old father of two, who lives on Long Island. A former Navy pilot, he had been with the airline for ten years. He had never imagined that a Mohawk plane would be hijacked, especially his, but then these are crazy times. He accepted the news with outward calm, and the first thing he did was to flash a hijack code to the ground alerting a network of law-enforcement agencies.

A few minutes later, the pilot made an announcement to the passengers. He said the plane would make an unscheduled landing at White Plains because of air turbulence, a curious thing to some of the passengers because the flight had been smooth up to that point. There was some grumbling; it would mean a long bus ride into the city, a big delay in arrival time.

The plane landed and stopped out on the runway, far from the terminal. The pilot told the passengers to get off, to walk straight away from the plane, and to keep clear of the propellers. Some of the passengers, as they departed, noticed the man standing behind the stewardess at the back of the cabin, but none apparently suspected anything was amiss. It was not until the somewhat bewildered passengers were standing on the runway that ground crewmen came running up and told them what was happening.

Inside the plane, the hijacker had made known his wishes. He wanted $200,000 in small bills and two parachutes. For this he would agree not to blow up the plane or kill the three crew members. He produced his bomb, something wrapped in a red blanket, and placed it on the floor near where he held the stewardess. All of this was relayed to the pilot over the intercom.

The pilot and copilot, William O’Hara, had locked themselves inside the cockpit. All communication with the hijacker and the stewardess, who remained in the rear of the plane, was over the intercom. This allowed the pilot to talk freely with the control tower without the hijacker knowing what was said.

On the hijacker’s orders the plane’s lights were doused. And in the darkness the four people inside waited to see what would happen.

Early communication between the plane and the tower was not made public. The hijacker was assured that his demands would be met. He was also told that it would take some time; the money had to come from a bank in Manhattan, and the vault had a time-set lock.

In the meantime, law-enforcement agencies had begun to mobilize. State and local police and F.B.I. agents converged on the airport, along with top Mohawk officials. The airport was sealed off. Two Air Force jet fighters were scrambled from their base in Rome, New York. John Malone, assistant director of the New York F.B.I. office, was alerted to the hijacking while he was attending a dinner party and he headed for the Westchester airport in his tuxedo to oversee the operation. Emergency equipment, a bomb-disposal unit, ambulances, light trucks were brought in. An identical Mohawk plane was made ready to serve as a chase plane for F.B.I. agents.

Forty minutes after the plane landed, it was refueled with enough fuel to take it eight hundred miles. Every airport and law-enforcement agency within that radius was put on alert. The small terminal at the airport began filling with reporters and photographers. And as word of the hijacking spread, sensation seekers began flocking to the airport. Despite the fact that approach roads were blocked by police, many of the curious abandoned their cars and climbed fences or sought other back ways into the airport. Police had to be strung out along the runways lest some of the curiosity seekers might attempt to get near the plane in the high weeds along the runways and frighten the hijacker into drastic action.

A little before nine, the parachutes were flown in from McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey. Homing devices had been concealed inside them so that authorities could track them. The parachutes were loaded into a van to await word to deliver them to the plane. But because of the time locks, officials were having trouble getting the money. As time passed, the hijacker grew increasingly impatient and anxious, and officials were growing more concerned for the safety of the crew members.

The safety of the crew was the foremost consideration of the F.B.I., John Malone would later reveal, but the hope was to get an agent close enough to get a shot at the hijacker. Twice agents had crawled under the belly of the plane, but there was nothing they could do.

In the small terminal, the wide picture window in the bar was the perfect place to watch all the action, and not surprisingly the bar was having its biggest night ever. You could sit there by the window and have your drink and watch the policemen scurrying about outside with their shotguns and rifles. And far out in the darkness on the runway you could see the little red flashing light that marked the plane. You could watch that light and wonder what it was like inside, wonder about the people in there and what their lives were like and what they were feeling now. But it seemed that few did. Mostly people laughed and told their theories about what was going on and repeated the next guy’s rumors and made jokes. It was exciting to be there. Rather like being at a big football game. It would be something to tell your friends about.

At eleven, a hush fell over the bar as everybody watched the reports of the hijacking on the TV news. But not a lot was known about what was going on now, and it was not easy to find out. Reporters wandered in and out of the terminal, interviewing people on the fringes of the action and sometimes one another. TV camera lights flicked on now and then as somebody was cornered who might have a tidbit of information. A few seemed to have contacts that were providing a little inside information, but mostly it was a matter of waiting (the waiting seemed endless) and not knowing.

Around midnight a private pilot came into the terminal carrying a little transistor radio that had been equipped with a device for receiving police calls. On it he had picked up the conversation between the tower and the plane. He was quickly surrounded by a crowd of reporters, who for the first time could hear for themselves what was happening out there in the darkness.

Shortly after midnight, the hijacker ordered the pilot to make three circles in place with the plane so that he could see if police were making an effort to get aboard. He had already set two deadlines for the money to be delivered. The second one had just passed and he was growing increasingly agitated.

“He’s some kind of religious fanatic,” the captain reported to the tower at twelve-ten. “He’s grumbling about making peace with his Maker and all that kind of crap.”

Fifteen minutes later, the F.B.I. agent in the tower told the pilot there would be another thirty-minute delay in getting the money.

“I told him about the delay,” the pilot said a few moments later. “He said one o’clock is the deadline.”

The hijacker wanted the parachutes now. He wanted somebody to drive a car by the left side of the plane and drop them under the wing where he could see them. The pilot said the hijacker had told him: “If they’re going to call my bluff, tell them I’m going to call their bluff. They’re going to see this thing go sky high. . . .”

“On and on he goes,” the pilot said. “He said the girl’s getting really upset in there. A few minutes later he said she’s okay.”

At twelve-forty, the F.B.I. agent instructed the pilot: “Tell him on the intercom the people in control who are running the show are concerned about the stewardess going out of the plane. If he forces her to jump, we’re fearful for her life. . . . He’s going to have to release the girl.”

Only one parachute would be delivered, the F.B.I. had decided.

“I told him,” the pilot reported back five minutes later. “He got pretty upset about it. He said, ‘Who said I’m going to force the girl to jump?’ He’s really getting riled up. He says she’s not going out, but he wants the two chutes out here anyway. He wants them right now. He wants the money right now. He’s screaming. He sounds like a real madman.”

The F.B.I. did not want to take two parachutes to the airplane.

“If we lose the girl, it’s not going to be from a jump,” the agent told the pilot. “The price of the second chute is the release of the stewardess.”

“He’s assured me the girl isn’t going to go,” the pilot reported back. “It’s no dice. . . . He says after we get airborne he’s going to search the aircraft and give us instructions. He just goes on and on. You can’t talk to the guy. He’s ranting and raving. He said otherwise he’d put a bullet through, I don’t know, this door or that door.”

A few minutes later, the tower tried twice without success to make contact with the plane. “Four-fifty-two, if you read the tower, will you flash your lights please.”

“We read you. Look, this guy is very, very, very upset. He needs positive action to reassure him quickly.” The tower reported that a car was on its way to the plane with the two parachutes.

“He repeated again if we don’t do anything, he’s going to put a slug through this door. . . . No one hear from the money, huh?”

It was almost one o’clock.

The money was on its way to the airport then. It had been borrowed from the First National City Bank in New York on the signature of an airline officer, but because of the time lock, it had taken hours to get into the vault to get it. The money was being brought in a convoy of cars carrying policemen, bank and airline officers. But the convoy had missed an escort, gone north of the airport and gotten lost. Now it was doubling back. The tower told the pilot the money wouldn’t make the deadline. It would be at least ten minutes more.

“He’s reassured Eileen she’s not going to jump,” the pilot reported. “I told him I wasn’t going to take off in this airplane with any explosives aboard.”

The parachutes were deposited under the wing as the hijacker had directed.

“He can see the chutes under the left wing,” the captain said. “He’s getting nervous. He says not to brighten the lights at all. He says he’s not only an expert parachutist, he’s an expert pilot. He’ll put a bullet through us and take this crate up himself. He’s chewing ice to keep himself calm. . . .”

At one-ten the money arrived and the tower told the pilot it was on the way to the plane.

“Shall I tell him that or just wait till he asks me again?”

He was told to tell him.

“Okay, we told him the money’s here and being loaded. He really didn’t say how he wanted it brought on board. He wasn’t very definite about it. He really doesn’t know what to do right now. . . .”

Moments later: “He wants the car on the left side of the airplane. He wants to make sure there’s not any state trooper that’s going to start shooting. He wants the guy to walk around to the copilot’s window and pass the money through the copilot’s window.”

“It’s obvious the money’s going to fit,” said the F.B.I. agent. “It’s just as obvious the chutes are not going to fit.”

“I hope the guys in the car aren’t visibly armed, are they? The guy says there’s somebody parked behind us. He wants him out of there. . . .”

The car with the money pulled alongside the plane.

“He wants the guy to get out and step in front of the lights before he proceeds around to the copilot’s window,” the pilot instructed. “He just said hurry up, men.”

The tower, however, had lost communication with the agent delivering the money. “You’ll have to open the window and yell to him,” the pilot was told.

As the suitcase full of money was passed through the window, pistols were slipped to the pilot and copilot. At one-thirty, the captain reported: “We got the dough. We don’t have the chutes.”

“He’ll have to go out and get the chutes or let an agent on board.” This from the tower.

“He wants the guy to leave the chutes by the door on the ground. He wants me to go out and get them. He wants the agent to take off. . . . Is he going to bring the chutes over to the door and leave?”

The F.B.I. wanted to try to get an agent on board and asked for suggestions as to how this might be done. The pilot could offer none.

“At the time the plan is to put someone on board,” the tower said.

“He just said he wants to see the money,” the captain said. “He seems to just be worrying about the money now. He doesn’t want to die. . . .”

The copilot went out through the forward cargo door and got the parachutes.

“Maybe we can talk to him about getting the bomb off,” the captain said. “What do you think?”

“He’s going to have to negotiate with us.”

“He wants us to put the money and the chutes in the back where he can see them. Can we get somebody through the copilot’s window?”

“The decision has been made not to put a man on board.”

“He’s got a gun on Eileen’s head. He just said he wants it [the money]. The copilot is opening the door back there. He’s going to take the stuff in back. You want this done?”

The tower suggested that the copilot might get close enough to the hijacker to “let fly on him.”

“He’s got a gun on Eileen.”

The tower suggested trying to trade the money for the bomb.

“He’s already got the money and the chutes now. . . . He’s going to give us two minutes to get off.”

The tower asked the pilot’s plans.

“What are you going to do at a time like this? I guess we’ll just go. . . . Is everyone clear of the airplane?”

The tower wanted to know if the hijacker had mentioned a destination. The pilot replied that he’d said something about a place three or four hours away.

“Make a very, very slow turn,” the tower advised, “because you have an automobile directly behind you. Stay out of sight of the car.”

“Don’t make any final attempt to get on or something like that,” the pilot said.

“The only car is the one right on your tail. . . . He wants to stay right behind you in case this guy comes out.”

At one-fifty-nine, the plane roared down the runway and lifted into the night. Reporters and cops lined the chain link fence beside the terminal and watched as the blinking red light that had been the focus of their attention all night disappeared in the darkness. Less than a minute behind, a second plane, without running lights, had taken off. This one carried F.B.I. agents.

The crowd inside the bar had dwindled somewhat by the time the plane took off. “There he goes,” yelled a drunk, who had been yelling the same thing all night and laughing uproariously each time. But this time he was right.

“Damn,” said a young man who had driven over from Connecticut with a group of friends and sneaked into the cordoned airport to watch the thing play out. “I thought we might see some action.”

The plane first headed northwest, then circled back over the airport, causing police to fan out over nearby roads in case the hijacker decided to jump near the airport. Then the plane headed north again.

Four Air Force jets were in the air to keep an eye on the plane, and the darkened sister ship carrying the F.B.I. men stayed close on its tail.

The hijacker ordered the pilot to take him to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, near the New York state line, keeping under 5000 feet. The plane arrived over the Pittsfield airport at two-forty-five and circled for fifteen minutes. The hijacker had changed his mind. He now wanted to go back to New York to the Dutchess County Airport near Poughkeepsie, about ninety miles north of White Plains. He wanted a four-door car standing by with the motor running, the lights on, and all the doors open so that he could make sure that no one was hiding inside. His plan was to take the stewardess with him as he left the plane. He warned that his bombs would go off if he were shot.

The Dutchess County Airport is in New Hackensack, about five miles south of Poughkeepsie. It is so small that it had been abandoned as a regular stop by Mohawk three years earlier. But the pilot was familiar with it.

Wesley Monroe was the controller on duty at the airport that Thursday morning. He had come to work at midnight after watching the reports of the hijacking on TV. When the hijacked plane had taken off from Westchester, he’d kept up with it from the beeps emitted by the tracking devices secreted in the parachutes. Now the pilot of the plane was calling him. The pilot gave Monroe the latest instructions, and Monroe immediately put out the alert.

Dutchess County Sheriff Lawrence Quinlan was called at home, and he ordered all of his men to the airport and all roads to the airport blocked. He instructed Chief Detective Albert Traver to make ready a car for the hijacker. Traver would turn over his own unmarked patrol car. Then Quinlan headed for the airport.

The plane landed at three-twenty-one. The chase plane came in a few minutes behind it. Rieth taxied the plane to a side runway. Detective Traver was in his car, ready to deliver it. When the plane stopped, Traver drove the car, a green Chevrolet, slowly out onto the runway and alongside the plane, stopping it so that the passenger door was parallel to the rear exit of the plane. He got out, opened all the doors and walked away several hundred yards to where the other law-enforcement officers were congregated.

The chase plane had stopped out of sight of the hijacker. The F.B.I. agents had bolted from the plane carrying rifles and shotguns and taken up positions around the hijacked plane. Four of them lay on the runway about forty yards behind the plane. It was a cold night, with the temperature in the low teens and a stiff wind blowing.

At a little before four, the copilot emerged from the plane carrying the suitcase of money. He put the suitcase in the back seat of the car, closed the rear doors and stepped away.

Then the stewardess appeared in the doorway of the plane. She was wearing her coat and carrying her suitcase. She looked pale and haggard. The hijacker was behind her, holding onto her shoulder. He had his bombs under one arm and the pistol in his hand. He led the stewardess hurriedly to the passenger side of the car. He got in first and slid across the seat, pulling the stewardess in after him. He put the bombs on the seat between them. Then he reached over and shut the door.

At that moment the F.B.I. agents made their move. Three charged the hijacker so that he could see them. The fourth came up from behind the car, yanked open the passenger door and thrust his shotgun inside across the stewardess’ chest.

“F.B.I.,” he shouted. “Surrender!”

The hijacker, caught by surprise, whirled, screamed. The pistol fired. And the F.B.I. agent pulled the trigger of his shotgun. The barrel of the gun was only inches away from the hijacker. The blast caught him in the chest at the base of the neck. His body jerked backward, then slumped forward, the pistol falling onto the floorboard. The medical examiner would later rule that the man died of a totally severed windpipe.

The F.B.I. agent yanked the stewardess from the car, and they ran, heeding the hijacker’s warning that his bombs would go off if he were shot.

When the bombs did not go off after a few minutes, the agents returned to the car, opened the driver’s door, and the body tumbled onto the asphalt runway. A bomb-disposal unit was brought up to dismantle the bombs, which they found to be two Boy Scout canteens filled with water. The pistol found in the car was a starter’s pistol, the kind used at track meets, and it had been loaded with a blank cartridge.

The hijacker’s body lay on the runway for two hours. The blood spilled out of his wound in a long, irregular puddle and congealed in the cold. All during this time photographers came and snapped their pictures. It was the kind of picture the F.B.I. and the airlines wanted everybody to see: the body of a dead hijacker lying crumpled in his own blood beside the plane he had hijacked. And later that day, and the next, the gruesome pictures would appear on front pages and TV screens all across the country.

The crew members were taken into the airport terminal and questioned. Their ordeal had lasted ten hours and they were tired and tense. After the questioning, they were whisked away in limousines with airline officers without talking to reporters. They later declined to tell their stories to the press on instructions of the airline and the Airline Pilots Association, both of which believe that not talking about hijackings will make them go away.

Papers on the body identified the hijacker as Heinrick von George. Sheriff Quinlan remembered him as a man who’d once had a couple of cigar stores in Poughkeepsie. He remembered because his men had to close the last store and sell off the equipment at auction. But even though others were sure of the hijacker’s identity, the F.B.I. would not officially give his name. They are careful about such things. They like to check fingerprints and all that.

At six-thirty that morning, shortly after the hijacker’s body had been removed from the runway and taken to a hospital in Poughkeepsie, John Malone of the F.B.I. held a news conference at the Dutchess County Airport to give details of the killing.

When a reporter asked him if he knew why the hijacker had chosen this airport as his destination, Malone said, “I don’t think he really knew himself what he wanted to do.”

Malone couldn’t have known, of course, but years earlier, when Heinrick von George was a young man and he and Barbara had only three children, they had lived in a trailer in Poughkeepsie. He worked during the day in a department store and at night he worked in a pizza joint near the trailer park to bring in extra money. One of the things that von George liked most to do then was to drive out to the Dutchess County Airport on Sunday afternoons with the kids to watch the airplanes come and go.

On the Thursday morning that Heinrick von George was shot, his eleven-year-old son Heinrick Jr. got up early as usual to deliver his paper route. Like the other members of his family, he had heard nothing about the hijacking the night before, and he didn’t notice the story on the front page of the paper that morning. He returned home a little before seven to find his mother trying to get the other kids up and ready for school. He had been home only a few minutes when there was a knock at the front door. His mother answered it still wearing her nightgown and robe.

The visitors were an F.B.I. agent and two local detectives. They wanted to ask some questions. Barbara von George couldn’t imagine what they wanted, but she invited them in. They were polite and very nice. They wanted to know about her husband. They asked quite a few questions. They wanted a detailed description, for one thing. Twice Barbara von George asked why they wanted all this information. She got no answer. When she asked a third time, she was told that there had been a hijacking in New York. At first, she thought her husband might have been a passenger on the plane. She wasn’t really worried. But then, after the questioning had gone on for nearly forty-five minutes, the F.B.I. agent told her that the plane had been hijacked by a man fitting her husband’s description and carrying his identification and that he had been shot and killed. She began to scream.

The older children had to be told, of course, and kept out of school. But Barbara von George didn’t want the three younger ones to know, especially Gary, who’d had the heart operation, because she didn’t know what the shock might do to him. After the officers left, she remembered that she’d told her husband to call her mother if anything went wrong, and she sent Mike, the eldest son, across the street to Mrs. Sullivan’s house to call her mother. Mike returned with the news that his father had called her mother the afternoon before, just a couple of hours before the hijacking. He’d said that he was in Pennsylvania to see about a job, and that everything was all right. Barbara von George went across the street to talk to her mother herself and to call other relatives. While she was there, the reporters began showing up outside.

Eventually, there was a big group of reporters and photographers, maybe a dozen, with cameras and TV equipment, all hovering outside the house. They frightened Barbara von George. They had her cut off from her children, and she didn’t want to talk to them, didn’t want them taking her picture. She wanted to scream at them.

As soon as the F.B.I. knew with some certainty that the hijacker was indeed von George, an agent telephoned the Red Cross in Brockton and asked if someone could be sent to assist the family. Harry Steele Jr., the executive director, and Albert Doyle, the chapter chairman, arrived at the von George house a little after nine. They were met on the porch by Mike, who at first thought they were reporters. He was hostile, but they were able to convince him that they were from the Red Cross and had come to help. So Mike told them his mother was across the street. They found her in near hysterics. The first thing they did was to ask her religion and call the family priest.

But there was still the problem of getting her through the reporters back to her house. At first, the Red Cross men planned to escort her and keep the newsmen away. She wanted to cover her head with her coat, the way the gangsters do. But the priest convinced her that she had known her husband to be a good man and that she should conduct herself with dignity now and not be ashamed. And she did. She pulled herself together, walked out of the house unassisted, her tears dried, her head held high. The newsmen stepped back. The photographers snapped their pictures, the TV cameras whirred, but nobody said a word. She maintained her composure until she stepped through her front door. And then she collapsed in hysterics again.

Should Gary be told? Could he be kept from finding out? The surgeon was consulted in Boston. It was decided to go ahead and tell the child.

He seemed to take it well.

The reporters were still out there, clamoring for some information to meet afternoon deadlines. So Harry Steele agreed to be family spokesman. He faced the newsmen and told them what he could. Some went away after that. But they came back. They stayed around all day, sometimes talking to neighbors, who couldn’t tell them much, except to say they didn’t know the von Georges very well and that the children seemed nice and well-mannered.

That afternoon, the newspapers arrived at the von George house, and it was all there in bold type on the front page: SHOTGUN BLAST KILLS BROCKTON SKYJACKER. And there was that awful picture. All the children looked at the picture of their father lying crumpled in his blood, as did their mother, but they couldn’t relate to it. It was too unreal. The words said it was their father, but it was not the man they knew.

“Looks like they shot his head off,” was Mrs. von George’s only comment.

The older children read the stories, too, getting the details for the first time, and it was all so fantastic, so alien, so unlike their father. They couldn’t picture him holding a gun, even a blank gun, at anybody’s head. He wouldn’t even allow a gun in the house. And the things he was quoted as saying. “That’s not daddy talking,” said Mike.

Later that afternoon, the relatives started arriving. Something had to be decided about a funeral. Von George had no life insurance. There was no money except the $11 he had left with his wife. Harry Steele started trying to find out if there might not be some veteran’s benefits, but he was having difficulty. Heinrick von George would have to be buried as he had lived—on credit.

The priest thought the body ought to be brought back to Brockton for burial, but Barbara von George decided she wanted to bury her husband in Peekskill, where her father was buried. It was the first real decision she had had to make since she’d been married. Her husband had always made all the decisions, or they had made them together. Making this decision caused her to realize how much new responsibility she had, and how vulnerable she was. She hoped it was what Ozzie would have wanted.

The family left for Peekskill the following day. That morning Harry Steele got a call from the F.B.I. A fingerprint check had shown that Heinrick von George was really Merlyn La Verne St. George, who had once served two years in San Quentin for stealing U.S. Government property. His family knew nothing of this. Could Steele please tell them? But by the time he got to their house, they had already departed for Peekskill.

On arriving in Peekskill that evening, Barbara von George would be jolted by that news in the local paper. San Quentin! She read those words and couldn’t believe it. Why hadn’t he told her? Her first thought was how this would affect the kids. She knew that if she had learned something like this about her own father when she was young that it would have troubled her deeply. And her husband had always been so strict with the kids. There was right and there was wrong and no middle ground. He lectured them frequently about obeying the rules. Transgressions were dealt with firmly and swiftly. She called the children in one at a time to tell them, and she was amazed at how they took it. It seemed to affect them hardly at all. They simply couldn’t see their father in those terms.

The local and New York papers were filled with stories about the hijacking that day, and as she read them, Barbara von George grew furious. The reporters had spread out through their old neighborhood on Dykeman Street, and some of the neighbors with whom they had disputes over the years (over fights between the kids, property lines, the kinds of things that are apt to develop in any neighborhood) had seized on this opportunity to get revenge. They called him a Hitler, a misfit, a very sick man. One woman said the world was better off without him, and a man wanted to give a reward to the F.B.I. man who had shot him. All the papers played these stories heavily. It would embitter Barbara von George forever against the press. And later, after her husband’s funeral, she would call some of the people who had said these things and let them know just what she thought about it.

The funeral was on Saturday morning, a private service at a funeral home with only the closest family members present, in accordance with Barbara von George’s wishes. The coffin was open. Barbara von George kissed the cold body, recalling the last time he had kissed her on the day that he left and how he held her face.

There was no long caravan to the cemetery, and no great mounds of flowers. Heinrick von George was buried in a back corner of the Assumption Cemetery without the little identification tag that usually marks new graves. On top of the grave was placed an arrangement of yellow gladiolas and gold chrysanthemums with two yellow ribbons bearing the words, “Husband,” and “Dad.”

Within hours of the funeral, just as Barbara von George was beginning to believe that it was all over now and that there would be no more surprises, another came. There was a mysterious call to her aunt’s house, where she had been staying, from a woman claiming to be related to her husband. She couldn’t imagine who it might be. She has an uncle who’s a joker, and he said, “Maybe it’s another wife.” And at that point, after all she had been through, she would have believed anything. She took the telephone and very coolly said, “What is your relationship to this man?”

The voice on the other end said, “I’m his mother.” And, as she would later remark, Barbara von George could have fallen through the floor.

Her husband had always told her that he had been born in Cincinnati, and that his parents, both middle-aged when he was born, had died when he was very young, leaving him to be reared by an older brother and sister, whom he apparently didn’t get along with very well and didn’t care to see again; he didn’t bother them, he told his wife, and they didn’t bother him. Beyond that, Barbara von George had never been able to find out anything about her husband’s past. He didn’t seem to want to tell, and, as was her nature, she didn’t question.

Now his mother was calling. Not from the grave, but from St. Paul, Minnesota.

Mrs. Thelma St. George had just learned from the newspapers that her son, who had disappeared from home twenty years earlier, had been identified as the hijacker who’d been shot and killed by the F.B.I. She also learned from the papers that he had a wife and seven children. It had taken her a while to find them, but she had. And now she was telling all of this to her newly discovered daughter-in-law.

Mrs. St. George had wanted to come to her son’s funeral, but since she had missed it, she decided to come to Peekskill anyway to meet his wife and the seven grandchildren she hadn’t known existed. She arrived two days later, bringing pictures of her son and other things of his, and Barbara von George began to learn a little more about the man she thought she had known all those years.

Mrs. St. George would not be interviewed about her son, so little is known about his early years. He was born in St. Paul on July 13, 1926, the first of seven children. His father was a career Army man (now deceased). His mother was a strong-natured woman, and he was very close to her. He grew up in Cincinnati and attended high school there. On the day after his seventeenth birthday, in 1943, he enlisted in the Navy. His mother told his wife and children that he saw combat and displayed to them the citations he received. He was honorably discharged in April, 1945. Nearly nine months later, he went back into the service, enlisting in the Army this time. It was while he was in the Army that he got in trouble. He was charged with stealing government property in 1947 and sentenced to serve one to ten years at San Quentin. He was paroled in 1949 and apparently returned to Minnesota, where his family was living. In 1951 he is believed to have received psychiatric treatment in the veterans hospital in St. Paul. Then in March, 1952, a warrant was issued for him, charging theft of $4,279 from a theatre in Duluth. The warrant was never served. Merlyn La Verne St. George had disappeared. Before he left, he called his brothers and sisters and told them that he was going. But he couldn’t face his mother.

When Barbara Gordineer met him in Peekskill early in 1953, he had become Heinrick von George and he had switched his ancestry from French to German. She was seventeen then, a high-school student, and he was twenty-six, although he lied to her about that in the beginning. They met because of a school dance. She had a date to go to the dance with a friend of her brother’s. But she got a call from this man who introduced himself as Ozzie von George, who told her he was a friend of her date’s and that he had learned she was about to be stood up, and he didn’t like that. He asked her to go with him, and she did.

At that time, von George was living and doing odd jobs at a convent in Peekskill. He told his future wife that he had come to the convent to recuperate from a heart attack. They courted for six months, and they married two days after his twenty-seventh birthday. They found a little apartment in a house on Main Street, and he took a job in a grocery store for $75 a week, which was not bad money at the time. It was the first of a long series of places they would live and jobs he would hold during their marriage. But they were happy, and the marriage apparently had a settling effect on von George, for even though he would have troubles, he would not run afoul of the law again until the night of January 26, 1972, when he thrust a blank pistol into Eileen McAllister’s side.

Two weeks after her husband’s funeral, Barbara von George sat at her dining-room table surrounded by her children, going through the family photograph album. She had been holding up very well, everything considered. But in the past couple of days the enormity of all that had happened seemed to have settled on her all at once and it was crushing. She had this jumpy feeling of being about to explode inside and not being able to do anything about it. She tried to walk it off, stepping nervously around the block, but it wouldn’t leave. So she talked. The words seemed to bubble out, punctuated by nervous laughter. Then suddenly in mid-sentence she would begin to cry. But the children were there and they could stop that. They had been her strength through it all, and when she started crying, they would tease gently and laugh until she would scold, “Don’t laugh at me!” And then she would laugh and it would be all right.

She had come to the wedding pictures. It had been a church wedding. Ozzie had wanted a less flamboyant civil ceremony, but she had held out, and now she was glad of it, because she had these pictures.

She picked up one of them and laughed. “Nobody would know it’s me now,” she said. “That’s what nineteen years and seven kids can do.”

Barbara von George was never a pretty woman in the conventional sense. But she has a vivacity about her, and a matronly attractiveness. She is only thirty-six, but already there is white in her hair. Like her husband, she put on weight over the years. She is plump, but her legs seem almost too small to support her weight. With her children around her, her appearance and bubbling nervousness give the impression of a mother quail with her brood. As she talks, she nervously kneads the tablecloth, bunching it before her, until Mike puts his hand on hers and smooths the cloth.

The children are all neatly dressed, alert, and well-mannered. Mike, seventeen, and Tommy, sixteen, have long hair. Mike is a fine baseball player, Tommy an honor student and chess player. Heinrick, eleven, is a Cub Scout (his mother is den mother, his father was a committeeman). The other children are Cynthia, fifteen, Gary, eight, Timothy, four and Barbara, two.

The older children are remembering things about their father.

“He always told us to be proud you’re German,” said Mike. That is why they had been so surprised to learn that they weren’t German, after all.

“He was proud of the race,” said Barbara von George, “but he wasn’t . . . you know, what do you call ’em?”

“He wasn’t a Nazi,” said Mike.

The time was recalled when a kid at school had drawn a swastika on Tommy’s notebook, and how angry his father was when he saw it, telling him to get it off. Tommy remembered the time he’d asked his father if he’d ever killed anybody when he was in the Army. “I remember him hollering, saying it was nothing to be proud of.”

Mike spoke of the baseball games in which he’d played and how his father always attended and how they would watch football games on TV on Sunday afternoons. Tommy talked about the chess games. His father always beat him at chess. He beat all his friends, too. “Nobody could beat him,” he said. Tommy had given his father a new chess set for Christmas.

They recalled, too, how their father, while selling insurance, had earned points for which he could claim a premium. The premium card had been around the house for a long time, but just before he left for New York, von George filled it out and sent it in, requesting a tent for the children. The tent was waiting for them when they returned home from his funeral.

“For nineteen years we lived a very happy life,” said Barbara von George. “We had never been in any trouble, other than financial, which other people have had, but we always figured we could pick ourselves up again, you know. . . .

“He loved his kids. He was very proud of his kids. When the little girl was born after having five boys and one girl, you can imagine, you know. I came home to find my dining room painted shocking pink.” She laughed. “It was such a shock. It really was. Oh, he was so thrilled to have another daughter. That’s why, you know, it’s hard to believe that he left all this. Really. But, as I said, who knows how your mind works?

“You know, to me he could’ve been . . . anybody who went out of his mind and did this. It happens all the time.”

Get instant access to 85+ years of Esquire. Subscribe Now! Exclusive & Unlimited access to Esquire Classic - The Official Esquire Archive

- Every issue Esquire has ever published, since 1933

- Every timeless feature, profile, interview, novella - even the ads!

- 85+ Years of outstanding fiction from world-renowned authors

- More than 150,000 Images — beautiful High-Resolution photography, zoom into every page

- Unlimited Search and Browse

- Bookmark all your favorites into custom Collections

- Enjoy on Desktop, Tablet, and Mobile

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

FICTION

FICTIONDunyazadiad

June 1972 By John Barth -

FICTION

FICTIONShorelines

June 1972 By Joy Williams -

ARTICLES

ARTICLESWhy Is This Woman Funny?

June 1972 By Harold Brodkey -

FEATURES

FEATURESHitting the Boiling Point, Freakwise, at East Hampton

June 1972 By Robert Alan Aurthur -

ARTICLES

ARTICLESThe Real-Life Death of Jim Morrison

June 1972 By Bernard Wolfe -

ARTICLES

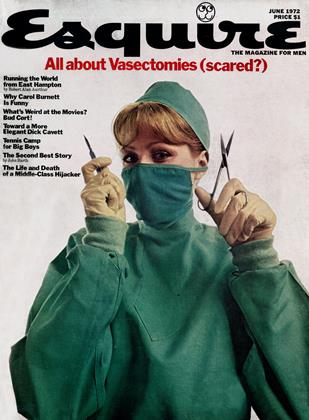

ARTICLESThe Incision Decision

June 1972 By John J. Fried