Hitting the Boiling Point, Freakwise, at East Hampton

Thirty years of hanging out on the beach—with Pollock, de Kooning, Ernst, Dali, Motherwell, Rivers, Rosenberg, Albee, Roth, Kopit, Javits, and the one-way crew of The Free Life balloon

June 1 1972 Robert Alan Aurthur BLAKE HAMPTONThirty years of hanging out on the beach—with Pollock, de Kooning, Ernst, Dali, Motherwell, Rivers, Rosenberg, Albee, Roth, Kopit, Javits, and the one-way crew of The Free Life balloon

June 1 1972 Robert Alan Aurthur BLAKE HAMPTONIt seems to me a person has to have mixed feelings about an enormous, candy-striped balloon taking off from a field near his house, especially when under the balloon is a gondola with three people in it whose intention is an unprecedented flight from Fireplace Road, The Springs, East Hampton, New York, to the first available landfall in France. On the one hand, you have to be in awe of anyone determined to set a world record, no one ever having flown a balloon across the Atlantic before. Also, that balloon, The Free Life, inflated, hanging high over neighbor George Sid Miller’s meadow, was some beautiful sight. And, though the attempt failed, the three adventurers lost forever somewhere off Newfoundland, the balloon did take off! I was there; I saw it happen. And take it from me: that balloon flight, a year ago last September, was the most bizarre event I’ve ever witnessed in this town—or maybe any town—and in the twenty-four years I’ve lived in the East Hampton area I’ve seen a few nutty things.

Yet, mixed feelings, because on the other hand, if suicide-by-balloon is merely the opening act of the Seventies, then the moment has arrived to look around in nervous wonder, suddenly faced with the realization that, like so many other sanctuaries, our little country carnival has become a five-ring Barnum & Bailey show. Until now, as a longtime seeker of refuge and premature fugitive from urban catastrophe, I have observed, with no real sense of impending doom, all the changes in East Hampton Town resulting from such phenomena as the late-Forties, early-Fifties Artists Incursion, the Great Homosexual Crisis of the mid-Fifties, and the Massive Grouper Invasion of the Sixties. While each succeeding wave left its mark, our town, which in over three centuries of its history has survived a lot of changes, appeared to remain basically unaffected. At least, so one hoped.

Forced to look around, one must conclude that over the years the quantitative changes have brought the inevitable qualitative change, and none of it for the better. Perhaps, then, it’s time to report on some of the key events, not that a chronicle of strange and sometimes wondrous doings is of more than passing interest, but because something has happened to this treasured retreat that is by no means unique to East Hampton Town. The blight has become universal, and if what is happening here is also happening everywhere, then what will the world be like without havens, without its quiet places?

To speak of the Town of East Hampton is to mean a conglomerate of smaller communities: from Montauk on the east, to Wainscott some twenty-five miles west; a narrow strip of farmland and shore, bounded north and south by Gardiners Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. The Springs forms the northern apex of a triangle: five miles to the southwest is East Hampton Village, and equidistant to the southeast is Amagansett. One hardly distinguishes between the two latter villages, both anchored on the ocean, but The Springs . . . is different.

Natives of this hamlet are called Bonackers and they are mostly named Miller, Bennett, King, Lester and Parsons. Though I’ve owned my house on Fireplace Road for seventeen years, and for the last six it’s been the only home I’ve had, the house, my house, is still known as the Old Parsons Place. And why not? The Parsons after all lived here and worked the land that runs down to Accabonac Harbor, or “The Crick,” for nearly two hundred years before me.

Real Bonackers speak with an accent that echoes early seventeenth-century English, and they’ve lived in this backwater on Gardiners Bay since the 1640’s. They are people sparing of words and movement, and one is certain they are not overjoyed at the influx of outsiders—artists, writers, and even balloonists.

But overall there is a residual resentment and some bewilderment as The Springs has been transformed, just in my time here, from a place with unique identity to a lot of subdivisions with names to attract buyers scanning the Sunday Times real-estate ads. Eighteen hundred virgin acres of the Hog Creek area have become Lions Head, Clearwater, and Deer Woods of Springs, dotted with houses that range from tacky to sumptuous butterfly modern. What used to be Barnes Hole has become Barnes Landing with its own Association and fenced-off beach. One sees Private signs on new roads and lanes, and special stickers are needed for beaches that were formerly free to all.

On the day of the balloon launching, local painter Herman Cherry arrived on the scene, checked it all out, measuring with the eye of a man whose roots here are deep, and said, “I think we’ve hit the boiling point, freakwise.”

And what a scene it was! A sparkling September Sunday, two weeks after Labor Day, the best time of year, when all transients are gone from our town. All the night before helpers from The Springs Volunteer Fire Department, clad in special red jumpers, had filled the balloon with gas drawn from tanks stacked on heavily laden trucks. By early morning, when hundreds of locals and regular weekenders began arriving, the balloon was already limned against the cloudless sky, large letters spelling The Free Life stitched vertically on the side facing the rising sun. Soon the field was jammed with celebrants; picnic baskets and kids; barking, running dogs; amateur photographers by the score, professionals from Life and the wire services; film crews from the networks. In the crowd one saw Jean Stafford Liebling, whose house is diagonally across Fireplace Road from the launch site. In fearful anticipation of this invasion, Miss Stafford had posted Keep Out signs all along her property, but now it was said she had befriended the balloonists and would probably write about the whole complex affair.

How easy it might be to plumb the psyches of two of the balloonists to strike writers’ gold. Rod Anderson and Pamela Brown were husband and wife, he described as a commodities broker, she an occasional TV actress. A handsome couple, young, ever-smiling, brave and confident. They lived in New York but were obviously not ready to settle for the routine paths to recognition, and, according to The Springs’ most celebrated philosopher, Harold Rosenberg of Neck Path, recognition is much of what it’s all about. As for the Andersons, though neither was a musician, three years before this September day they had decided to give a concert at Carnegie Hall, on piano and harp, had given themselves two years to prepare. A beautiful idea, and one wishes the balloon fantasy hadn’t intervened; had they limited their concert audience to friends, there was no chance of getting killed at Carnegie Hall. But once the balloon idea took over the Andersons spent at least $100,000, selling the piano, borrowing most to prepare for the flight. This was no cheap balloon, friends, not the kind you buy in Central Park. This balloon and gondola, with radios and camera equipment, was meant to sail to Europe.

Rod Anderson had been up in a balloon once before; Pamela, who had never been up, made her decision to accompany her husband on the very morning of takeoff. Ignorance might explain their belief in the incredible venture, but the third member of the crew was something else. Malcolm Brighton, an Englishman, an aeronautical engineer and a veteran balloonist, had left a wife and children at home when he flew to America to join the party. He must have known two things: one, The Free Life had to fly more than a thousand miles further than any balloon had ever flown; and, two, it would never happen.

If there were any pessimists that morning of the launch, they contained themselves, overcome perhaps by the audacity of the idea, the sheer beauty of the whole scene. Two helicopters wheeled overhead; a small plane circled, waiting to follow the balloon on its first leg across Gardiners Bay and Long Island Sound. The balloon itself, a huge inverted teardrop, strained against its lines, urged by a stiff morning breeze.

It was that breeze, gusting to fifteen knots, we were told, that delayed the flight. But no one complained; it was enough just to be there. Most of the morning Malcolm Brighton, blond and muscular, bare-chested in the hot forenoon sun, hung in the rigging, tightening things, testing burners, measuring the wind, pushing and pulling myriad mysterious objects. It was the consensus opinion of the crowd that he seemed to know what he was doing. And there was Rod Anderson, dressed in his Free Life red jumper, modestly longhaired and moustached, taking inventory in the gondola (alleged to be unsinkable), accepting gifts, posing for pictures, keeping out of Brighton’s way. Pamela, pretty and vivacious, her hair dark and shoulder length, stayed out of sight until flight time. She was, we were informed, “making up her mind.” But her father was ever-present, a tight-jawed man in a black alpaca suit and narrow-striped tie, maybe the only man so dressed within a hundred miles. That black suit said “the money,” and, rumor had it, Mr. Brown was a Kentucky lawyer who’d financed most of this venture.

Runners continually brought weather reports to Brighton, and at noon it was announced that if, as was predicted, the wind dropped under seven knots by two p.m., the balloon would be off. People settled down to their picnic lunches, dogs ran and barked, kids ran and shouted, and The Free Life, its gondola temporarily deserted, was held to earth by Springs firemen, exhausted by their efforts, sustained by free brandy.

As the wind velocity diminished, the tempo around the gondola increased. Suddenly there were two flags, American and British, snapping in the rigging; now the three balloonists were aboard, waving and laughing. The crowd collapsed into a solid mass, and as Brighton called for volunteers to move the gondola closer to Accabonac Harbor at the foot of the meadow, everyone responded. A great rush swept the balloon a hundred yards from its original mooring; lines were dropped, and sandbags spilled over the side of the gondola.

I was filming the takeoff from atop a rock, and next to me my friend, film producer Alfred Crown, said, “They’re sure in a hurry to die, aren’t they?”, marking the only time I’ve ever known a film producer to be right; there was an uncontrolled frenzy about that moment, fueled by the realization that if The Free Life wasn’t airborne now then it would never be, and that would be an intolerable tragedy.

Suddenly Malcolm Brighton signaled the helpers off, and as the gondola was freed the crowd continued to surge with it, cheering and shouting, and for just a moment this was no lunatic dream, but a noble voyage, a beautiful happening. The gondola bumped once, twice, then rose into the air just yards short of the tiny, boat-filled harbor. A shout of triumph seemed to help lift the balloon higher and higher and The Free Life set a steady, rising, northeast course toward Gardiners Island. People jumped, screamed, laughed; elderly men and women waved straw hats, and some cried.

Had the balloon fallen into Gardiners Bay (as some predicted it would), no one would have minded; in fact, most would have been relieved to see the adventure end quickly, even if vaingloriously. Because it was the simple act of taking off that counted, you see. All the effort, the money, yes, the courage, had only to do with that single moment of leaving the meadow. That was controllable. From then on it was just a balloon ride, its length determined purely by the vagaries of the wind.

But The Free Life did not fall down, not then anyway, and not until some thirty hours later when it and its three passengers were lost without a trace. Still, I will always remember and have photographic evidence of that glorious, foolish moment when it left George Sid’s meadow and sailed off over Gardiners Bay. Through my camera, a last view of the balloonists was Malcolm Brighton hanging above the gondola in the rigging, flanked by the two flags, grinning and waving, then toasting us all with a bottle of Moët et Chandon.

All right. There is certainly nothing wrong with seeking a moment of unique recognition, even dying for it; surely, over the years in East Hampton most of the people I’ve known have sought recognition as a specific goal. But if some of them have been a little crazy, or more than a little self-destructive, they’ve also been some kind of artists, not balloonists. More important, East Hampton was a haven, not an end or a taking-off place; and if there were bizarre happenings, those were the exception, not the rule.

Twenty-four years ago, I drifted here on the rise of the post-World War II artist influx led by Jackson Pollock, and, even earlier, by the Lebanese-born woman painter (and gourmet cook to her friends), Lucia. Lucia had arrived in the Summer of 1939, lured from Paris, along with Fernand Léger, by her close friends Sara and Gerald Murphy who’d heard the approaching thunder of war and offered refuge. That summer Lucia stayed with the Murphys on what was then the Wiborg estate, Sara Murphy being born a Wiborg. The property, including a beach, extended west from the Maidstone Club and is no more, having been carved into smaller and very expensive holdings, and Wiborg Beach is now mostly known as Pink Beach. What has not been carved up is the Maidstone Club, a gothic fortress nestled in the dunes, at all times your super Wasp’s nest, a sub-haven against those of the Jewish persuasion and itinerant Gypsies. It may be apocryphal, but I choose to believe the story that once New York Senator Jacob Javits was invited to the Maidstone to play tennis, and wherever he stepped the grass turned brown.

(That was the year when I was a proud guest at the Senator’s birthday party, and over the singing of Happy Birthday, he was heard to proclaim: “And here’s the cake my wife Marion caused to have made.”)

Individually, Maidstoners appear gentle, jocular, and even broad-minded, but banded together they seem to have a way of taking over.

In 1942 and ’43, drawn by Paris-based friendships and Lucia’s cooking, exiled painters and writers, mostly Surrealists, made Amagansett’s Atlantic Avenue Beach their summer base. That beach, broad and gleaming off-white, is part of a hundred-mile stretch of sand and dunes that was, and is, one of the most beautiful beaches in the world. During World War II it became known as Amagansett Coast Guard (as distinguished from East Hampton Coast Guard, and, in a newer generation, Artists’ Beach, six miles to the west), still later as Off-Broadway Beach (as distinguished from East Hampton Main, or Sardi’s Beach), and currently as Martell’s, or Asparagus Beach (as distinguished from any other beach in the world).

Relationships among the Surrealists get a bit complicated here, so please pay attention. Max Ernst was here with his then-wife Peggy Guggenheim, who had been instrumental in his escape from Europe. The painter Dorothea Tanning was here, whom Max would later marry. Salvador Dali was here, with whose wife Max had run off in 1922 from another beach in the South of France, abandoning his first wife and infant son Jimmy. Jimmy Ernst was here, quite independent of his father Max, who’d been of no help when Jimmy fled Europe, alone, in 1938. Lawrence Vail, once married to Peggy Guggenheim, was also here, as was their daughter Pegeen, who married painter Jean Hélion, a recent escapee from a P.O.W. camp. Léger and Anai's Nin stayed with Lucia, Anaïs writing a book in which Lucia is a leading character. The Chilean Surrealist Matta was here, as were Arshile Gorky, the sculptor Noguchi, and architect Pierre Chareau. Marcel Duchamp came to play chess with Max Ernst, and André Breton, the spiritual leader kibitzed. Breton was here with his wife Jacqueline, and the American sculptor David Hare came with his wife, who was the daughter of Roosevelt’s Labor Secretary, Frances Perkins. Because the Department of Immigration at one time was under Mrs. Perkins’ authority, it was partly through the efforts of Hare and his wife that all these peculiar types got so easily to our shores in the first place. That accomplished, Hare departed with and later married Jacqueline Breton.

If all that isn’t incestuous enough, we must record that Jimmy Ernst was then living with a lusty lady for whom his father had recently had a powerful, unfulfilled yen. That lady later opened a gallery in New York, giving Jimmy his first one-man show of paintings, at the same time rejecting Jackson Pollock. Max Ernst had no problems about showing, because his New York dealer, Julien Levy, was generally at his side on the Amagansett Beach. Max did have a problem with the F.B.I. who kept interrogating him as an enemy alien.

The F.B.I. was also intrigued by another group of foreigners seeking refuge here who, unlike the artists, would never be able to return home: for several summers the entire Spanish Republican government-in-exile used East Hampton as its seasonal headquarters, some of them living in the Sea Spray Inn at Main Beach. One wonders if the inn’s owner, the late Arnold Bayley, knew whom he was harboring; some years later Bayley emerged as local leader of the Liberty Lobby, a right-wing clan which on the credit side espouses repeal of the income-tax laws, at the same time urging preventive nuclear attacks on every country in the world, possibly excepting Paraguay, reputed refuge of Martin Bormann. In the Fifties, Bayley ran ads in the local newspaper, The East Hampton Star, which mixed bucolic appeals to attract guests to “Sea Spray By-the-Sea” with heavy warnings that Commie-rats were to be found behind every giant elm on Main Street. Until recently, in addition to the Gideon Bible, Sea Spray residents would find piles of flaming hate literature, and, typical of East Hampton, no one thought that in the least incongruous.

The Surrealists and Spanish Republicans were mostly gone when I first came here in the Summer of 1947, my arrival the result of knowing both Lucia and Jimmy Ernst. As a writer I sometimes sold short stories, but my assured income, $30 a week, came from my efforts as a very junior partner in a record company, Circle, which documented primitive New Orleans jazz and blues, and for which Jimmy designed the album jackets. The founders of Circle were Rudi Blesh and the late Harriet (Hansi) Janis. Hansi, a close friend of Lucia’s, was separated from her husband Sidney Janis in every way but an interest in their stunning collection of modern paintings; Sidney Janis, not yet a gallery owner (that was a year later), nonetheless represented a few select painters, of whom Lucia was one.

And so my first weekend here was spent with Rudi and Hansi at Lucia’s, in a house she’d bought in Amagansett with her wartime-acquired husband, inventor Roger Wilcox. A sprawling ex-boardinghouse, it, along with twenty acres, had been bought for a pittance, mainly because of its decrepit condition: Over the years, however, Roger has created his own work of art, a hand-built conversion of special beauty. But then everyone was penniless. Except for Jimmy Ernst, who made $75 a week in the Warner Brothers art department (and lived in his father’s East Fifty-eighth Street apartment—Max having departed for Arizona—surrounded by about two million dollars’ worth of art), my thirty-per made me one of the heavy-cash men. But if Lucia and Roger’s house lacked a heating system, it never suffered from insufficient warmth, and I remember evenings in the big kitchen, that summer and the next Christmas, as the most pleasurable of my life. While I’ve never recommended poverty to my children, I’ve always pushed struggle, and in those days at that time struggle for recognition was the common catalyst stimulating all. Robert Motherwell, for instance, was firm in his stated conviction that within five years he would be hailed as America’s foremost painter. On hearing this, Jackson Pollock would smile a little and shake his head; or there might be a bellowing hassle. Jackson knew better, and, in fact, just about when the five years were up, and it was clear that Pollock would make it, Motherwell having to settle for a little less, Motherwell abandoned his Pierre Chareau-designed quonset-hut home in East Hampton and departed forever.

With his wife, the gifted painter Lee Krasner, Pollock had moved here in 1947, buying a roomy, old frame house on Fireplace Road in The Springs, which Lee still occupies. There are the familiar stories of his digging for clams off the end of his property that bordered on ’Bonac Crick, and the paintings he traded to Springs General Store owner Dan Miller for staples. There were also forays to Georgica Pond to catch huge blue claws that often disappeared into one of Lucia’s bubbling pots. I recall one such trip when we were joined by a familiar-looking whitehaired man who emerged from Juan Trippe’s huge dune house and introduced himself as Edward Stettinius. When we’d caught enough crabs, Stettinius indicated he’d like to keep his share. Jackson grumbled that anyone living in the Trippe house could afford to buy his dinner, but before he could enforce his point, the former Secretary of State disappeared into the mansion, proudly carrying his blue claws.

Once, Roger Wilcox and Pollock walked the twelve miles to Montauk, their old Fords both out of commission and no money for repairs, hoping to get jobs at a small, newly opened fabric factory. The jobs were available—at a dollar an hour—but no money in advance to fix one of the cars. They walked back, still unemployed.

I didn’t really know Pollock well, though I saw him often over the ten years before his death. I was intimidated by Jackson. Most of the time he was a quiet, shy, gentle man, but when he worked a fierce concentration propelled him into orbit. Sometimes he would dance around one of his canvases totally possessed, revealing a furious, volcanic power. I remember being reminded of an enraged, brilliantly performing heavyweight; Jackson tore into a canvas the way Joe Louis destroyed Max Schmeling.

When Pollock was drinking, the rage took a totally destructive form, a subject not to be exploited. One story, though, may tell as much about the way this place was as it does about Pollock:

It began as an ordinary evening at the Wilcoxes’ with one of Lucia’s dinners. When Pollock was a guest, hostesses might hide the booze to remove temptation, but this night Lucia had bought one quart of beer as a special treat. Nothing went amiss; then at ten o’clock Jackson quietly excused himself, saying he wanted to take a five-minute walk. When by two a.m. he hadn’t returned, Roger went to find him.

Getting into their ancient Ford (no top), Roger knew there could only be one place to look, and he headed directly for Frank Eck’s Elm Tree, the only game in town. A gloomy roadhouse, it would later, under new management, become the Elm Tree Inn of Homosexual Crisis fame, and still later it would be, as it is now, Martell’s, headquarters for the Great Grouper Invasion. But then it was a sleazy bar with even sleazier cabins in back, and Eck’s was shunned by respectable folks always, its clientele hard-drinking fishermen, mostly unshaven, some out from the city with stringy-haired women, often not their wives. Whatever their real origins, the fishermen were all lumped together by locals as “Portugees,” to be avoided and ignored.

Eck, himself, was a big man, a deputy sheriff (self-appointed), who often rode around Amagansett on a white horse and wearing a cowboy hat. He apparently harbored deep resentment against Pollock for many reasons, not the least of which was that Jackson could claim to be a real cowboy from Wyoming, who knew an ersatz when he saw one.

When Roger entered the bar he found Jackson in loud argument with Eck and two “Portugees,” the subject long forgotten, but Wilcox recalls the tone as not yet threatening. Jackson promised to leave after Roger joined him in “just one drink.” Not a drinking man, Roger remembers a minimum of five and then, aroused by thumps and cries, becoming aware that as Pollock seemed to be demolishing the bar, Eck was beating him with a baseball bat. A mild, noncombative type, Wilcox nonetheless went to his friend’s rescue, at which point, he was beaten with the bat. Between Eck and the “Portugees,” both intruders were heaved out onto the Montauk Highway. It was five o’clock in the morning.

Lee Pollock had long since gone, but Lucia was awake and waiting when the Ford and its bleating and bleeding occupants returned. Prepared to be tolerant of Jackson’s problem, she reacted violently at the sight of her drunken, wounded husband, on top of which Pollock had smashed his boots through the windshield of the Ford. Thereupon, Lucia began flailing at Pollock with a broomstick, chasing him into the house where he escaped up the stairs and locked himself into a bedroom. An hour later, reacting to crashes in the hallway, Lucia emerged from her room, where Roger had passed out, to find Pollock hammering on doors as he looked for a bathroom. In hot pursuit with the broomstick, Lucia drove America’s soon-to-be most celebrated artist from the house. But her trial was not yet over. At nine that morning, in full regalia and on his white horse, Frank Eck rode into the Wilcox yard to effect an arrest of the men who had not only wrecked his bar, but, he claimed, had revealed themselves as dedicated Communists plotting to overthrow Amagansett.

With non-diminishing fury, and once more wielding her broomstick, Lucia propelled Eck from the yard at full gallop, and except for an echoing voice proclaiming all artists as dirty Reds who should be driven from the community, he was not heard from again. At which point Lucia packed a suitcase and left for New York.

Later that week a contrite Pollock phoned to add to Roger’s pleas; not only did Jackson assume all responsibility for the debacle, but he also said he had somehow raised ten dollars to replace the windshield. Lucia returned, but she will tell you even now with a trace of regret it was never the same again.

This past summer our Kultur Haus, Guild Hall, presented its twenty-third annual Artists of the Region show, and it is difficult to remember a time when the Hall’s galleries didn’t display the most advanced contemporary painting. But in 1949, a summer I spent in Amagansett sharing a $400 house with Hansi Janis and Rudi Blesh, the galleries functioned as gloomy clubrooms, dominated by murky, brown portraits. In that year a local woman of unquestioned respectability, Roseanne Larkin, deciding it was time the community took notice of the artists who’d settled here since the war, prevailed on Guild Hall to clear its walls for a catchall show. Impressed by Lucia’s recent exhibit at the new Sidney Janis Gallery, Mrs. Larkin turned full responsibility of inviting the painters over to Lucia and another resident woman artist, Gina Gnee. The storm aroused by that first show, 17 Artists of Eastern Long Island, was even then laughable and today an interesting curiosity.

The furor centered around Pollock, whose giant canvases had just emerged in all their threatening glory. It wasn’t the public that created the problem; most locals just gazed blankly at the incomprehensible drippings with some bemusement, then turned to the soothing Soyer brothers of Montauk or the accomplished seascape watercolors of Amagansett’s Ray Prohaska. Not the public, no, but some of the artists themselves who angrily proclaimed Jackson a fraud, saying his work demeaned the show and reduced it to a joke. The summer was marked by a lot of screaming and several fistfights.

Undeterred by the commotion—to some extent thrilled by the attention— Guild Hall board members took the plunge, and in 1950 (my first summer in The Springs, in which I shared a $600 house with Jimmy Ernst and his wife, Dallas) none of the representational artists was invited in an exhibition of 10 East Hampton Abstractionists. Robert Motherwell and James Brooks made their first appearances, along with Pollock, Lee Krasner, John Little, and the late Wilfrid Zogbaum. Again fists flew, but mostly I recall Jimmy Ernst’s generally sunny nature turning to anguished hurt when he was not invited to show. Till then what had been basically amusing to observe became painful as I identified with the rejection of my closest friend.

But wheels have a way of turning. Jimmy’s work has earned him his own house and studio in the Lily Pond section of East Hampton Village, as well as a Johansen-designed home in New Canaan, Connecticut. Now himself on the Guild Hall board, he helps initiate plans for the shows, one of them last summer a retrospective of the late John Ferren, and the recent works of Hedda Sterne and the sculptor Ibram Lassaw, three longtime artist-residents of The Springs. The Outs become the Ins become The Establishment—and so it always goes.

The growth of the artist invasion can easily be measured from the list of Guild Hall invitationals: many arrive, few leave. To make up for Motherwell’s disappearance in 1953, Bill de Kooning pops in, along with Alfonso Ossorio, the latter remaining a full-time resident. The next year, 1954, Franz Kline, sharing a rented house in Bridgehampton with de Kooning, makes a one-time appearance as does Jacques Lipchitz. Conrad Marca-Relli shows up and settles in; so does Larry Rivers.

Rivers, though little noted as an artist in that high-tide year of 1954, was to make his temporary mark in another field. To help support himself, Larry played baritone saxophone in a band at the Elm Tree, by this time under new management, and I will testify that for some three summers Rivers played the worst baritone saxophone in the entire history of that bastard instrument. What he lacked in technique—which was everything—he made up with fervor and volume. It was always my theory that the straight couples who then crowded the Elm Tree, mostly to dance, were driven away by Rivers’ honking horn, thus creating the vacuum that brought in the gays, who weren’t interested in dancing. More of that later. . . .

In 1955—a good year, because it was that spring I bought my house—Guild Hall introduced 11 New Artists of the Region, and by 1956 the tempest of the early years was gone, if not forgotten. Moses Soyer was back, exhibiting alongside Jackson Pollock, whose notoriety and success surely made him a celebrity, if not a universally accepted master; and if the majority of the artists from then on were Abstract, or Pop, or Minimal, well, that’s how the world was going, and one worried more about natural hurricanes—the mid-Fifties being big years for Carol and Diane—than man-made ones. In ’54 Hurricane Carol swept the Montauk studio of painter Jim Brooks out to sea, and three years later, after his place had barely survived Diane, Jim and wife Charlotte moved themselves and house to Neck Path in The Springs.

Pollock’s death in August of 1956 came as a shock, if not a surprise. Forbidden to drive by the town officials, he drove anyway. His obvious anguish, his inability to break through into new forms—and why was he expected to?—led to a work-paralysis and obsessive drinking. The total of his behavior was the dropping of one shoe, and after a couple of years of what appeared to be unspeakable pain, he let the other fall. I have passed the place on Fireplace Road where he crashed his car thousands of times since. For more than ten years two small, bent trees marked the spot, and I always hoped once those trees finally died I’d no longer be reminded. They disappeared a couple of years ago, and with them the instant memory of the crash. Now, passing the house where Lee still lives, and the studio where Pollock worked, one tends to remember the functioning, dedicated painter, the man who turned it all around for a whole generation of lesser artists and made their way easier.

Pollock is buried in The Springs’ Green River Cemetery (mostly brown and nowhere near any river), his grave atop a small rise at the very rear marked by a large nature-shaped rock. From the gravesite you can look out over the small cemetery, past the graves of A. J. Liebling, poet Frank O’Hara, painters Ad Reinhardt and Stuart Davis, and directly across the two-lane tar road, Accabonac highway, there is Willem de Kooning’s house. When he sees Jackson’s memorial stone, as he must every day, de Kooning, now the titleholder, is surely reminded of what can happen to America’s most celebrated painter who drinks and drives. Himself known to enjoy an occasional taste, de Kooning is chauffeured whenever a car is necessary; but mostly he can be seen solemnly pedaling his bicycle between house and studio about a mile and a half apart, the studio built just off Fireplace Road no more than a couple of hundred yards from the spot where Pollock was killed. Local authorities, regretting their reluctance to take a firmer hand with Jackson, now cherish Bill de Kooning as an essential asset to be preserved. One hears that on at least two occasions de Kooning has been briefly and gently incarcerated for—how else can one put it?—drunken bicycling.

This latter-day concern for one of its artists is, I hasten to add, not necessarily the norm, nor is the tolerance town-wide. Though artists and their camp followers have brought money and prestige, a tradition of hostility goes back to the early Fifties when a local scion and sportsman publicly announced that suspicious Guild Hall doings would bring a flood of “Jews, Communists, and other queers.” Wrong about Communists (we’ve always had an insignificant number), the speech nonetheless was the opening shot in the anti-homosexual drive which soon became a crusade. Whether or not there is any real connective between the artists and a subsequent influx of gays, by the mid-Fifties we had a full-fledged Crisis. Lured by the surface benevolence of the community (and the fact that Fire Island had become saturated), gays arrived in ever-increasing numbers, gathering in great conspicuous crowds, by day at the Two-Mile Hollow Beach, by night at the Elm Tree. The resultant outcry from the straights was underscored by our then chief of police who once observed: “On any given weekend afternoon you can go down to Two-Mule and see three-four hundred head of queer.” Local voices called for “nightstick justice,” and our police responded, towing away or tagging cars parked at the beach and Elm Tree. The inn eventually lost its liquor license, not as a more legitimate result of Larry Rivers’ honking, but because an undercover cop managed to entice an enticer at its bar.

A reasonable voice throughout the crisis was that of the young editor of The East Hampton Star, Everett Rattray. Along with magnificent beaches, Gardiners Island, and the Long Island Rail Road, Ev is one of our natural wonders; his mother, Jeannette Edwards Rattray, the Star’s publisher, traces her ancestry in town back to its beginnings in the mid-seventeenth century. During the Great Homosexual Crisis, Rattray was barely out of Dartmouth and the Columbia Journalism School, and just beginning to exercise control of the Star, then a commonplace country weekly reflecting a community position somewhat to the right of Cotton Mather. Since then, often enraging entrenched opinion, Ev has converted the Star to a bright, acerbic, award-winning journal which still serves local needs with an overlay of sharp, fresh writing. His own editorial views range from an early anti-Vietnam-war position and a pro-youth bias, to a consistent hard-line attack against arrant land developers, speculators, and all those spoilers who would destroy the abundant indigenous beauties of East Hampton Town.

At the time when dozens of “head of queer” were being herded in and out of our local pokey in weekly games of harassment, Ev gently suggested editorially to the embittered gays that perhaps the real threat was less abnormal sexuality (for, after all, some of our most respected citizens were, and are, closet queens) than it was their extreme visibility. For example, mass nude sunbathing at Two-Mile Hollow was not a thing to allay the fears of the Ladies Village Improvement Society. A word to the wise, Rattray thought.

No more than a few days later the police conducted its biggest beach bust, arresting’ a great cluster of bare-assed sun-worshipers and dragging them to the town lockup. To Rattray’s dismay, one of the arrestees was a middle-aged local artisan of repute, father of one of the Star’s faithful employees. Then and there Ev broke a tradition by deciding he wouldn’t make known the names of those busted, and as he escorted the local gentleman away from the jail he couldn’t understand what might have compelled him to cavort nude with the transient gays, considering the risk and all.

“Why, Charlie?” (not the man’s name) he asked. “How did you get into something like that?” “Hell, Ev,” Charlie said, with some indignation, “I read about it in the Star.”

A dozen years later all is cool on the gay front. Today, at Two-Mile you’ll find gays to the left, families to the right. No one is hassled; the crisis is long over. Optimists will tell you this is how it will always happen in East Hampton: as in pre-Maoist China, each succeeding wave of barbarians will be absorbed. Pessimists will ask if there is not a limit. There is no doubt, they do keep coming. . . .

Never precipitating a crisis, yet helping to swell the ranks, have been writers, their families and/or groupies. (A writer’s groupie—not to be confused with a Grouper—is, generally, a healthy young woman who inevitably runs off with an artist.) At this writing we are bounded on the east by Edward Albee of Montauk, on the west by Truman Capote and Peter Matthiessen of Sagaponack; dead center are such as Berton Roueché, a permanent resident since 1948, Dwight Macdonald, Murray Schisgal, Peter Maas and Neil Simon. Until his death, John Steinbeck lived in Sag Harbor, and twenty years ago at Lucia’s one might meet John Dos Passos and Archibald MacLeish, who were also friends of Sara and Gerald Murphy.

In the early Fifties novelist Donald Braider’s Main Street book shop was a popular hangout for artists and writers; the lure was twofold: an incredible inventory, and Patsy Matthiessen, Peter’s first wife, who didn’t sell many books (no one could afford any) but stood around a lot looking beautiful. When the shop failed, Braider abandoned East Hampton to teach at a New England boys’ school and write historical novels. Peter Matthiessen, not yet an established writer, had moved here with the intention of fishing commercially for a living. But the poetry of midnight seining, a romantic concept that had attracted other writers and artists, soon gives way to the earthbound truth that fishing, Bonacker-style, is a grim, grinding, ultimately unrewarding way of making a buck. Matthiessen still lives here, an eminent writer who fishes now and then for pleasure.

For many years a magnet for other writers, and a man who has exercised equal influence in the art and literary worlds, Harold Rosenberg has lived in The Springs, with his wife, writer May Tabak, since 1943. When I first met Harold he was a sometime poet but mostly essayist and critic for magazines like Partisan Review and Commentary, always the dominant figure on the beach, the center of a swirling group of young painters and radical writers. One of those rare people with the genius to detect, then synthesize a new movement in art, Harold, through the force of his own aesthetic judgment, helps shape a totally different form. In part responsible for the school of Abstract Expressionism, he denies he gave it the name, more modestly admitting he labeled and defined the subform of Action Painting.

But during the Winter of 1950-51 Harold’s glories as America’s Breton, professor at the University of Chicago, and art critic for The New Yorker were yet to come. We were both wintering here, and I was encouraged to show him several stories I’d written; not only did Harold offer constructive help and encouragement, he also insisted on sending my work to editors with whom he had influence.

I recall a time when we were driving into New York together on a freezing February afternoon. An incredibly painstaking writer, sometimes spending months on a critique for which he might get fifty dollars, Harold spent much of the three-hour trip lamenting, with great humor, his own lack of success. He claimed that to date his greatest moment had come in the prewar W.P.A. days when a raging Neanderthal Congressman had made a speech in the House denouncing the entire federal arts program, with a special reference to “. . . the Red poet, Rosenberg.”

“At least,” said Harold, “the bastard made it official I was a poet.” Then, after a reflective pause: “Remember, kid, you take your recognition where you can get it.”

Having given up my sinecure of $30 a week, I could not on that February day have felt further away from my moment of recognition, but, in fact, solvency was barely around the corner. The very next summer (spent in my own $400 house on Louse Point, The Springs) I met writer David Shaw, forming a friendship now in its twenty-first year. Through David, who was working in the brand-new medium, television, I met another summer resident, producer Fred Coe. Incredible!—a person could actually make a living moving full-sized people around a ten-inch screen. Within a couple of years a whole clutch of TV dramatists spun around Fred, most summering in East Hampton, all of us short. Somewhere in the world there may have been a tall TV playwright, but I never met him. Gore Vidal pretended to be tall when he wrote for television, but he wasn’t.

More to the point, the brief phenomenon of New York live television in the mid-Fifties had an extraordinary effect on East Hampton. For one thing, East Hampton Main was transformed into Sardi’s Beach as directors and actors followed producers and writers, and very soon the action was not just limited to television, the beach becoming completely dominated by people who operated in TV, the theatre, and New York films. To paraphrase our chief of police, on any given weekend afternoon, in addition to seeing “a few head of celebrated queer,” you might also witness on one blanket a script conference; on another a producer hustling units for an upcoming play; on yet another a production meeting between director and scenic designer. And moving from group to group might be agent Peter Witt, his latest Europe-acquired actor in tow, saying, “Meet Horst Buchholz, a young man destined to be a great star.” Outlasting any of the productions, Horst Buchholz, and even the character of the beach itself (in recent years a hangout for teen-agers and Groupers-over-thirty), was the Sunday-morning softball game, a spin-off from Sardi’s Beach, in which I pitched for one side, producer Kermit Bloomgarden for the other. In its sixteenth year of a consecutive run, with an entirely new cast, the game has a lot of kids in it now, some with funny beards.

Changes! At the beginning of the Sixties the artists were driven to East Hampton Coast Guard when Amagansett Coast Guard was captured by a brand-new flood of newcomers: analysts, college professors, and intellectuals led by a former secretary of Leon Trotsky, soon augmented by an elite group so forceful that for the brief time they were here the beach was known as Jewish Novelists’. There were Philip Roth, Mordecai Richler, Wallace Markfield, and, for just one season, Saul Bellow. A strange, dour group, glowering a lot when together; then people would report, “. . . But when you get Phil alone (or Mordecai or Wally) he’s really hilarious!” No one ever said that about Saul. A very temporary group, to be sure; muttering dark curses, they came and went within three summers.

And none too soon, because now the deluge! Sweeping all before them, and a direct link leading to the Great Grouper Invasion, was a mob of such ebullience that all memories of Jewish Novelists were wiped clean as Amagansett Coast Guard became Off-Broadway Beach. Led by Arthur Kopit, Jack Gelber and Jack Richardson, this bunch turned the beach into a daily Olympics. Unparalleled machismo: running, jumping, muscle-flexing. A sunwashed spectacle of ball-throwing, Frisbee-skimming, girl-grabbing; browned bodies flashing and flipping into the waves. Touch football melted into volleyball overlapping with softball, all somehow becoming contact sports.

Dominant in that wild pack was a man we’ll call Chuck Weston. Big and burly, with close-cropped blond hair, Weston’s jumping and flexing surpassed all others. He had two Rolls-Royces, one of which he loaned to Gelber. Like future balloonist Rod Anderson, Weston was a broker (and is there a study to be made correlating the brokering of stock and commodities with unattainable fantasies?), his involvement with the dramatists stemming from a novel he was writing about the American Indian. The book had already been bought by Marlon Brando for a big-budget film, Chuck said, and Weston and his wife, a charming, quiet woman, were shopping for a very expensive house with the impressive sum paid for film rights. All one summer the progress of the book, and an informative commentary on the plight of the Indian, were Weston’s daily contribution to discussions held in brief breaks between contests. Listening intently and with growing interest, was Arthur Kopit. If Weston ever missed a day of the Olympics it was because, his wife would report, he was deep into rewrites, and everyone respected that. The Westons looked at many houses, put down a substantial payment on the most imposing available.

In truth, as we learned the next winter, there was no book—not a page, not a word, and the money for houses and Rolls-Royces had been embezzled, some from his fellow athletes but most, a hundred thousand dollars, being the life savings of Weston’s corner groceryman in the West Village. If people were shocked at our only real impostor— we’ve had many pretenders but no other impostor—no one was angry. And several seasons later Arthur Kopit’s play, Indians, surely stimulated by Weston’s deception, was produced on Broadway and subsequently bought for a film for a half-million dollars, not by Brando but by Paul Newman.

If Chuck Weston’s non-book proved profitable to Arthur Kopit, the impact of the Off-Broadwayites, leading to the Groupers, was surely a mixed blessing for the entire area. All those brown, young, male bodies, some of them belonging to straight bachelors, drew great clusters of unmarried, bikini-clad young women, in turn luring other young bachelors. Actually, in female-Grouper terms, there is no such thing as a young bachelor, just an unmarried man who hasn’t yet met the right girl. And so, in the mid-Sixties one became aware that many of the houses, mostly in Amagansett but spilling to East Hampton and Montauk, were being filled by groups formed from ads in The Village Voice. And, like the gays of ten years before, they were flooding here from a saturated Fire Island. The Elm Tree, which had lain dormant for years, was reopened as Martell’s; instantly, the same people who line up outside the East Side singles bars in New York swarmed to line up in Amagansett.

(Year-round residents of East Hampton, Midge and Tom Paxton were in Martell’s last summer for the first and only time. The next day in Bohack’s Midge was approached by a girl she’d never seen before: “That was a very cute guy you were with last night. How early did you get there to pick him up?” “About eight years ago,” Midge said.)

Giving Amagansett Coast Guard its new identity of Asparagus Beach, the Groupers stand by the hundreds, and from a distance they look . . . well, like asparagus. Investigating this latest phenomenon, one learns that there are houses of under-thirties and over-thirties, the latter gathering, seated, at East Hampton Main. There are straight male and female houses, as well as gay houses; there are houses of married couples with children, even houses with divorced men with children. But mostly there are the co-ed houses, always advertised in the Voice as “swinging,” but one suspects there is more to the promise than to the eventual action. On closer examination East Hampton Groupers would seem to be pleasant, middle-class young people, most of them in or on the fringes of the professions, who seek what lonely people have always sought. It was best summed up by one young woman, who, when asked what the Groupers wanted out of a summer here, said, “Well, the girls want a commitment, and the boys want to get laid.”

In reaction to this penultimate threat (the very latest being the youthful longhairs, harassed even more than the gays were), the town has imposed regulations against Groupers, but since real-estate agents and individual owners can make a great deal of money on groups, boosting the rent in all cases, the laws are ignored and quite unenforced, if not unenforceable. Thousands have come, jamming Amagansett’s main street outside Martell’s on Saturday night and in Fromm’s at brunch time on Sunday, and there is no indication the invasion is slackening. Ev Rattray believes the Groupers are being absorbed, his gauge being that some are beginning to subscribe to the Star. Hoping to lessen the hostility from the general community, the Groupers are now interested in becoming part of the fabric of their summer environment. The first step is to know it, and the best way to know it is through the Star.

But, unhappily, it would seem that total absorption of any outside group is impossible. After settling on East Hampton Coast Guard some dozen years ago, the artists proliferated until the beach became known as Artists’ Beach, described as that in Chamber of Commerce brochures and in the Star. Then, apparently, the critical number was hit, freakwise, and in 1970 East Hampton Village Trustees (the Village being an autonomous political unit) ruled that a special parking sticker given only to Village residents would henceforth be required for that beach. Since most of the artists live in other parts of the town, their beach was lost. An angry, summer-long counter-campaign of meetings, protest picnics, and ads in the Star threatening boycotts of Village shops proved totally ineffective. The anti-artist position was summed up in two quotes in The New York Times: The Village mayor, a pleasant, somewhat fumbling gentleman, since voted out of office, said, “If they don’t like it here, let them go to the Cape.” A woman summer resident of Lily Pond, wife of a wealthy stockbroker (what is it with brokers?), said, “Let them take cabs.” (Her husband’s father, when once asked the question, “What’s the latest dope on the market?” is reported to have answered, “My son.”)

Yes, the residual hostility is always there. In September, 1970, after our new high school was built, school-board president Frank Brill, while cheerfully admitting he knows nothing about art, not even what he likes, nonetheless brought before the board a proposal that the new school’s bare, institutionlike walls be covered with works loaned by local painters. This modest proposal was instantly met with shrill protest against “pornographic art.” One of the board members insisted that before he’d let any of these paintings into the school he’d first have to know “what all those weirdos are doing out there in the woods.” Brill appointed a committee to look into it. The walls are still bare.

Well, what are those weirdos doing out there in the woods? One Springs novelist we know about; his plumber finked on him to the cops, reporting the writer was growing a fine crop of pot in his yard. The writer was busted, which is not the worst of it; he also lost the services of the plumber. We also know about painter Robert Gwathmey whose urge to display a peace flag on his house two summers ago would have gone totally unnoticed if not for the patriotism of an Amagansett insurance-selling neighbor who had the artist arrested. It is safe to say that while Peaceniks are in the ascendancy here, the Warniks and Bombniks are in heavy majority. Another weirdo, unidentified, sent out anonymous letters two summers ago to a half-dozen prominent people, saying the wife of a film director was telling dreadful things about them. The real mystery was why only six letters? The lady in question was known to say dreadful things about everybody—never, however, with malice, and only the truth. But full-time weirdoism, of a nature too awful to describe, has mostly become a lost art in The Springs as most of us devote every waking moment to a losing battle with the gypsy moth. Early last summer, in opposition to all available scientific information, Ernestine Lassaw, wife of sculptor Ibram, swore she had beaten the plague by spraying her thirty acres of trees with ordinary detergent. Hopefully, others followed Ernestine’s example. Springs trees ended just as stripped as any others . . . but were very clean.

Not to be counted among the weirdos. . . . Strike that! Surely to be counted among the weirdos is Gaby Rodgers Leiber, whose husband Jerry is the popsong lyricist and publisher. A man who wrote Hound Dog at age sixteen deserves what he gets, and what Jerry Leiber has is a wife whose limitless energies have lifted her far beyond an earlier career as a successful stage and TV actress. In the winter Gaby directs Off-Off-Broadway plays; in the summer she Organizes Projects. Some years ago Gaby staged two plays, one by the late Frank O’Hara, in the yard of a friend, employing artists as actors, and a crowd of some five hundred greeted the evening with wild enthusiasm. Thus encouraged, Gaby revived a version of the evening three years ago in the yard of painter Syd Solomon, not just coincidentally the star of the night, this time in plays written and performed by artists. When the lights often failed to work, and the sound broke down, no one could hear the dialogue or see the actors, so again there was acclaim from an audience who’d come mainly for the subsequent drinking and grabbing. The thing about artists as actors and/or playwrights is it’s like an octogenarian dentist who tap-dances on TV: people applaud wildly simply because he’s doing it.

Two summers ago the evening, by now a classic, was held in my pasture on Labor Day, again with new plays written and performed by artists, and you cannot believe the phone calls during the weeks of preparation; the screaming and feuds. The hate. Unfortunately, the night of the performance both lights and sound worked (Gaby had a rabbi on the lights and someone’s eight-year-old genius kid on sound), and in spite of guest appearances by Taylor Mead and a very pregnant Viva, the plays were received by some five hundred people mostly in stony silence. On top of which my tape recorder was ripped off, a minor mishap easily balanced by the fact that Dwight Macdonald performed with barely controlled hysteria in drag makeup. You don’t often see that!

Two weeks later, at the balloon ascension, Gaby wryly admitted, “The plays didn’t work, so enough of that.” Thank God, I thought; maybe, finally, a little peace. But then she said, “So next summer I’ve decided on films.” And so it was, last summer: fifty-five people, mostly artists, shot 8mm cassettes on any subject of their choosing, the developed film hooked together without editing and shown in all its wretched entirety at the V.F.W. Hall. A catastrophe greeted with general hilarity and mutual congratulations. To be fair, there was one brilliant six-minute segment, a tale of lust among clam-diggers, written and directed by playwright Murray Schisgal, and starring Murray, Audrey Gellen Maas, and yours truly as Lance Fireplace. A winner!

Whatever Gaby has planned for next summer, it may or may not be worth hanging around for. But that’s not the real question: the real question, after nearly twenty-five years, is what’s happened to the haven? As more and more people find the cities unlivable, as they must, more and more flee to places like East Hampton, as they have every right to do. But then, of course, places like East Hampton become like the cities. Not long ago I was in New York having lunch at the Russian Tea Room with a friend who’s owned a house in East Hampton for nearly twenty years. Just returned from a scouting trip to Canada, he was selling his house, and is buying a hundred and twenty acres in Nova Scotia. He said artists were just beginning to move there, land and privacy as cheap and available as in East Hampton twenty years ago. He said I should check it out, and I said I’d think it over.

Leaving the Tea Room, we turned toward Seventh Avenue. Two cabdrivers were having a fistfight at the curb. Actually, I told my friend, on the advice of a painter and a novelist who were also leaving East Hampton, I was planning to look into Ireland. A drunken woman was screaming at a small boy in front of Carnegie Hall. Fine, my friend said, you’ve got to go somewhere. Just as we turned the corner to head south on Seventh, a man darted to the newsstand, punched the blind news dealer, scooped up his victim’s money, and raced down into the subway. The blind man started to cry. As my friend started screaming for the police, I said good-bye, turned and ran a half block to the parking lot to reclaim my car. I set a personal daytime record for the drive home: two hours and four minutes.

The thing is: although we have a growing drug problem in East Hampton; although we now have to lock our doors and take car keys out of the ignition at night; and although two Springs eight-year-olds were mugged by older kids for their trick-or-treat U.N.I.C.E.F. money last Halloween . . . I figure we’re about five years away from blind men being robbed in East Hampton.

After that? Well, as my friend said, you’ve got to go somewhere!

Get instant access to 85+ years of Esquire. Subscribe Now! Exclusive & Unlimited access to Esquire Classic - The Official Esquire Archive

- Every issue Esquire has ever published, since 1933

- Every timeless feature, profile, interview, novella - even the ads!

- 85+ Years of outstanding fiction from world-renowned authors

- More than 150,000 Images — beautiful High-Resolution photography, zoom into every page

- Unlimited Search and Browse

- Bookmark all your favorites into custom Collections

- Enjoy on Desktop, Tablet, and Mobile

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

FICTION

FICTIONDunyazadiad

June 1972 By John Barth -

FICTION

FICTIONShorelines

June 1972 By Joy Williams -

ARTICLES

ARTICLESWhy Is This Woman Funny?

June 1972 By Harold Brodkey -

ARTICLES

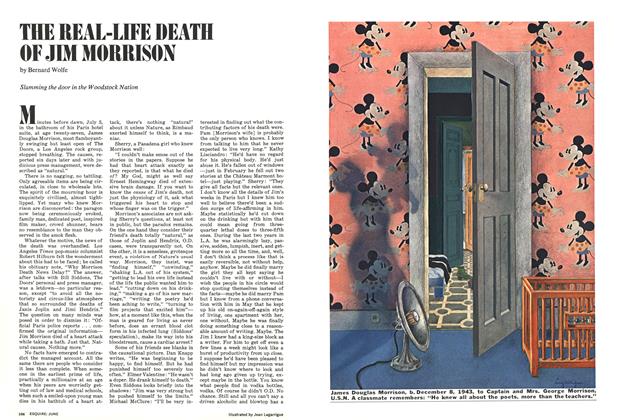

ARTICLESThe Real-Life Death of Jim Morrison

June 1972 By Bernard Wolfe -

ARTICLES

ARTICLESWho Cares What Happened to a Middle-Class Hijacker?

June 1972 By Jerry Bledsoe -

ARTICLES

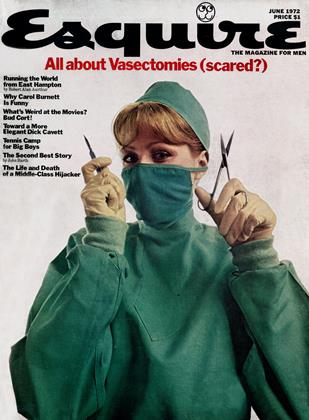

ARTICLESThe Incision Decision

June 1972 By John J. Fried