Stranger at the Party By the Lady Who's the Champ

June 1 1975 ARNOLD GINGRICHStranger at the Party by the lady who's the champ

ARNOLD GINGRICH

Publication by Random House of Helen Lawrenson’s Stranger at the Party gives this page a twoway stretch. First, to call your attention to the fact that Helen Lawrenson’s long-awaited volume of memoirs contains twelve chapters, of which only five had prior publication (with different titles) in these pages. These were, in case you’ve forgotten, or missed any of them, the ones about Bumpy Johnson, now called “Underneath the Harlem Moon”; Clare Boothe Luce, called “The Delicate Monster: An American Success Saga”; Condé Nast, “He Knew What He Wanted”; Bernard Baruch, “The Oracle of the Obvious”; and the one starring the author herself, called “The Case of the Nearsighted Spy.” So if you read them all, and thought you were getting the book serially, this is to let you know that you’ve seen only forty-two percent of it. And if you missed one or more of these, or indeed if you read any one of them, the odds would appear pretty good that you will run not walk to the nearest bookstore to get the rest. By fairly common consent, reader reaction seemed to indicate that these were the liveliest pieces to infuse these pages since Latins Are Lousy Lovers first exploded on them—and no other verb seems adequate to suggest the international sensation that caused—as far back as October, 1936.

And that brings up the matter of this page’s other-way stretch. Because going back to Latins Are Lousy Lovers, her first free-lance piece, written during her last days as the last managing editor of Vanity Fair, Helen Lawrenson has since run up a record, through the last of the five chapters of her memoirs to appear before publication of Stranger at the Party, of sixty-seven articles contributed to our pages, or one for every year of her age. This is a record that will undoubtedly stand for some time to come. She could coast from here on, giving us only a piece a year until she’s ninety, without having to look over her shoulder to see if anybody’s even remotely likely to catch up, given that the terms of this particular championship are limited to feature articles in the main body of the book.

The only reason for bringing up that last consideration is that the overall championship, numerically, was awarded as far back as October, 1971, to Jesse Stuart for the grand total of his stories and poems published in our pages. But that count did include individual poems, and since these were most often published in groupings of several to an issue, the actual count was obviously inflated to that extent. At that time I wrote, with literal truth, “Jesse Stuart is the all-time champion contributor. Despite two heart attacks after the handicap of a late start— he didn’t appear in our pages until the June issue of 1936—he has appeared in our pages with stories and poems seventy-nine times. The runner-up would still be Scott Fitzgerald. Although he had but six years left to live when he first appeared, with Zelda, in our third issue, February, 1934, he appeared forty-five times between then and 1941.”

True enough, as far as it went, but since it was a discussion of bylined contributions it overlooked the large category of anonymous pieces by feminine contributors, the most famous of which was certainly Latins Are Lousy Lovers. Helen Lawrenson’s next half-dozen pieces were also published anonymously. Although Zelda Fitzgerald had snuck in with Scott, sharing the by-line for two successive issues, The Magazine for Men got self-conscious about publishing feminine by-lines after its first year, and eschewed them, resorting instead to anonymity or initials until the Forties, when the war years let that policy lapse. But meanwhile, though Helen Brown Norden, as she was then, was to become and remain our favorite contributor, her code name around our shop was “That Greek, Anonymous.” You can see how that would lead to a certain confusion whenever the question of number of by-lined contributions came up in any sort of competitive connection.

So it’s a pleasure to make honorable amends and count every piece she got cash, if not credit, for over the course of these last nearly four decades, with the conclusion that in the feature-article category at least, the records of The Magazine for Men now clearly show that a lady is the champ.

(Continued on page 48)

(Continued from page 8)

What else can I tell you about Stranger at the Party? Well, it’s probably silly to apply a how-to subtitle to a memoir, but a perfectly apt one in this instance would be “How To Be Happy Though Sophisticated.” That’s no earthshaking scoop, of course, since every time I’ve referred to Helen Lawrenson in print these many years, man and boy, it’s been with some variation on the term The Happy Sophisticate. Here’s how she deals with that attribute in Stranger at the Party:

“I have scant capacity for brooding. It may be true that most men lead lives of quiet desperation, but I lead one of quiet content, snug in my invisible cocoon of self-spun magic. I wake up cheerful and brisk every morning, doubtless an obnoxious trait to those who can’t even say Hello until they’ve had their

coffee or their pill. It puzzles people who think I ought to be miserable or dissatisfied or depressed or worried, because it is a common assumption that no one is really happy, at least not for long at a time. Some twenty years ago, my friend George Wiswell got a job with one of the top book publishers. He called me and said he had a great idea for a book I could write. Despite my paralyzingly lethargic attitude toward work, I met him for lunch, because I liked him and enjoyed talking with him. I expected that he would suggest I write something flippant about sex, as ever since the Latins piece, editors seemed to think I was a sort of comical Baedeker of the bedroom. It turned out this was not at all what George had in mind. He wanted me to write a book about how to be happy, because he said I was the only truly happy person he’d ever known. Everyone else was going to psychiatrists, or drinking to escape, or getting ulcers, or having nervous breakdowns, or taking pills to sleep and pills to stay awake; and they all felt sorry for themselves. His idea was for me to reveal my secret formula for happiness and then we’d all make a lot of money and that would make him happy. I informed him that it was embarrassing enough to be considered a sex expert with-

out becoming Pollyanna the Glad Girl sex expert.

“When I went home, I told Jack I didn’t know the secret, anyway. He said, T do. You’re happy because you have no ambition.’ I asked him to explain, so he did. ‘You’re not disappointed because you haven’t attained a set goal, because you’ve never had a goal. You’ve no guilt feelings about cutting people’s throats to get ahead ; you don’t have to suck up to anyone in order to use them or make “contacts.” There’s no sweat. Failure is unimportant if you don’t crave success. But you can’t write a book and say that the secret of happiness is to have no ambition. That’s un-American!’”

Though she hasn’t done quite that, still I think she’s come closer to it, in Stranger at the Party, than anybody else ever has. And not only as a happiness secret, but also as a success secret, it’s not bad. Over twenty years ago I commented in this space on her total lack of ambition, saying that like the Parisians who see no sense in travel because they’re already there, she doesn’t itch to “get anywhere” as an author.

So it’s pretty tremendous, reading this wise and witty and wonderful memoir, to see how impressively far she could get without really trying. -Hf

Get instant access to 85+ years of Esquire. Subscribe Now! Exclusive & Unlimited access to Esquire Classic - The Official Esquire Archive

- Every issue Esquire has ever published, since 1933

- Every timeless feature, profile, interview, novella - even the ads!

- 85+ Years of outstanding fiction from world-renowned authors

- More than 150,000 Images — beautiful High-Resolution photography, zoom into every page

- Unlimited Search and Browse

- Bookmark all your favorites into custom Collections

- Enjoy on Desktop, Tablet, and Mobile

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

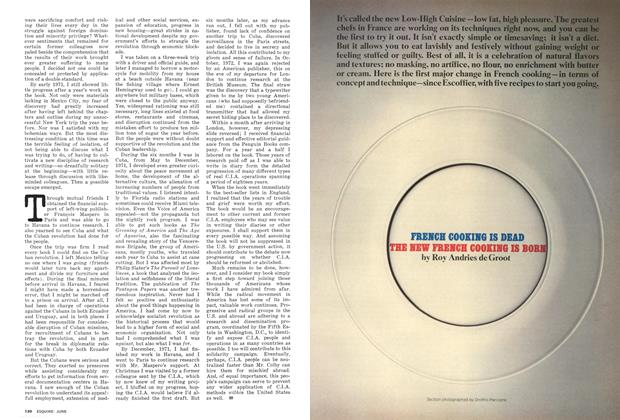

French Cooking Is Dead. The New French Cooking Is Born.

June 1975 By Roy Andries de Groot -

PROFILES

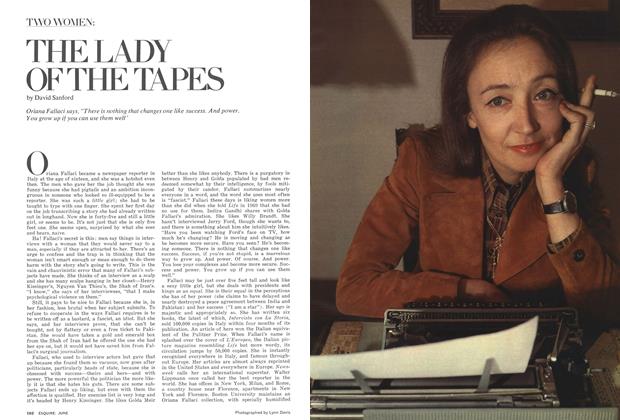

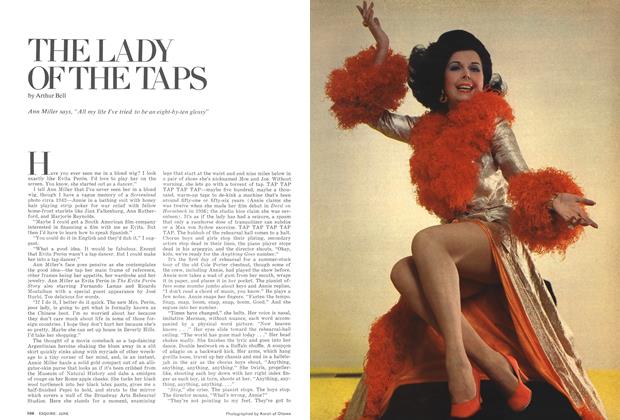

PROFILESThe Lady of the Tapes

June 1975 By David Sanford -

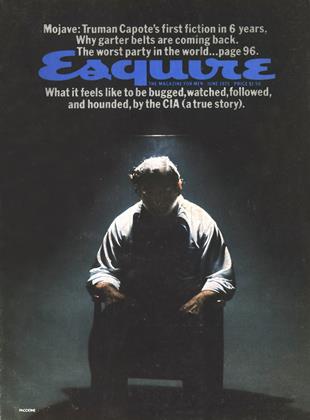

Fiction

FictionMojave

June 1975 By Truman Capote -

How Does It Feel To Be Bugged, Watched, Followed, Hounded and Pestered by the CIA?

June 1975 By Andrew St. George -

TWO WOMEN

TWO WOMENThe Lady of the Taps

June 1975 By Arthur Bell -

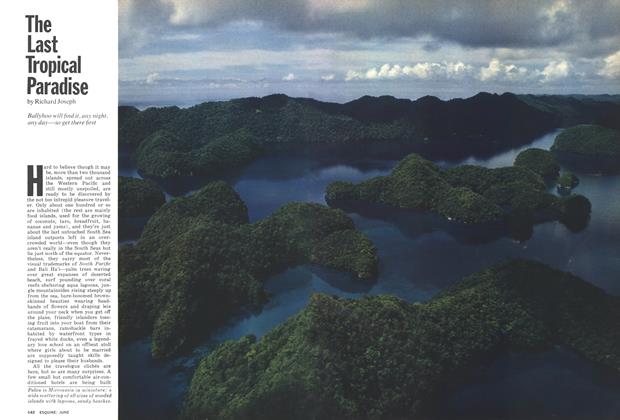

The Last Tropical Paradise

June 1975 By Richard Joseph