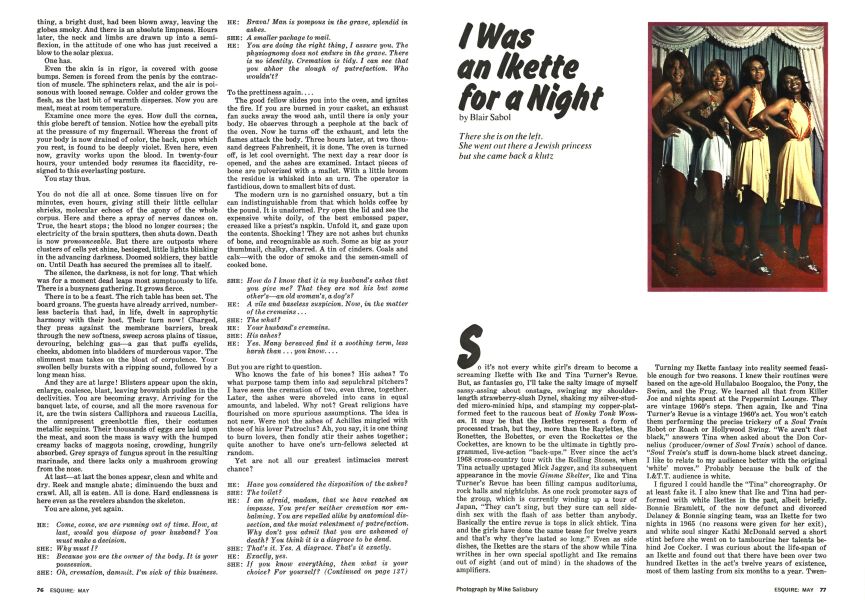

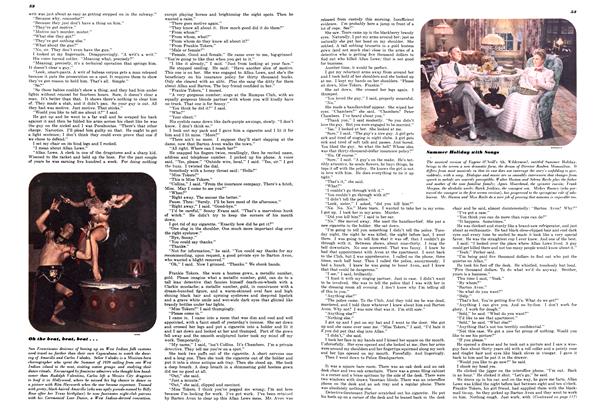

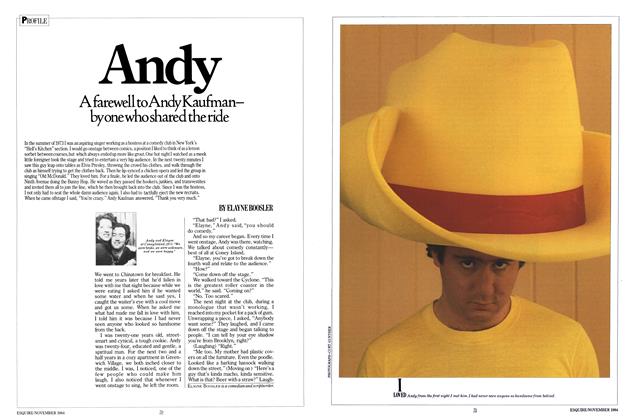

There she is on the left. She went out there a Jewish princess but she came back a klutz

May 1 1975 Blair Sabol Mike Salisbury, Curt GuntherSo it’s not every white girl’s dream to become a screaming Ikette with Ike and Tina Turner’s Revue. But, as fantasies go, I'll take the salty image of myself sassy-assing about onstage, swinging my shoulder-length strawberry-slush Dynel, shaking my silver-studded micro-minied hips, and stamping my copper-platformed feet to the raucous beat of Honky Tonk Woman. It may be that the Ikettes represent a form of processed trash, but they, more than the Raylettes, the Ronettes, the Bobettes, or even the Rockettes or the Cockettes, are known to be the ultimate in tightly programmed, live-action “back-ups.” Ever since the act’s 1968 cross-country tour with the Rolling Stones, when Tina actually upstaged Mick Jagger, and its subsequent appearance in the movie Gimme Shelter, Ike and Tina Turner’s Revue has been filling campus auditoriums, rock halls and nightclubs. As one rock promoter says of the group, which is currently winding up a tour of Japan, “They can’t sing, but they sure can sell side-dish sex with the flash of ass better than anybody. Basically the entire revue is tops in slick shtick. Tina and the girls have done the same tease for twelve years and that’s why they’ve lasted so long.” Even as side dishes, the Ikettes are the stars of the show while Tina writhes in her own special spotlight and Ike remains out of sight (and out of mind) in the shadows of the amplifiers.

Turning my Ikette fantasy into reality seemed feasible enough for two reasons. I knew their routines were based on the age-old Hullabaloo Boogaloo, the Pony, the Swim, and the Frug. We learned all that from Killer Joe and nights spent at the Peppermint Lounge. They are vintage 1960’s steps. Then again, Ike and Tina Turner’s Revue is a vintage 1960’s act. You won't catch them performing the precise trickery of a Soul Train Robot or Roach or Hollywood Swing. “We aren’t that black,” answers Tina when asked about the Don Cornelius (producer/owner of Soul Train) school of dance. “Soul Train’s stuff is down-home black street dancing. I like to relate to my audience better with the original ‘white’ moves.” Probably because the bulk of the I.&T.T. audience is white.

I figured I could handle the “Tina” choreography. Or at least fake it. I also knew that Ike and Tina had performed with white Ikettes in the past, albeit briefly. Bonnie Bramlett, of the now defunct and divorced Delaney & Bonnie singing team, was an Ikette for two nights in 1965 (no reasons were given for her exit), and white soul singer Kathi McDonald served a short stint before she went on to tambourine her talents behind Joe Cocker. I was curious about the life-span of an Ikette and found out that there have been over two hundred Ikettes in the act’s twelve years of existence, most of them lasting from six months to a year. Twenty-nine-year-old Ester Jones ranks as the longest-lasting Ikette, with her five years of gut ’n’ grind service. Very few Ikettes have gone on to become stars or lead singers. Some of them end up as nameless recording session singers for Stevie Wonder or Marvin Gaye, others become bit players in movies like Super Fly and Truck Turner. Ike and Tina are famous for purposely picking losers for girls, explains one ex-Ikette, “simply because they are no threat to the act. And Tina can work and manipulate them better.” Apparently once you make it as an Ikette, Tina remakes you and your entire personality into a Tina twin, with her same wig, red spatula fingernails, large high-glossed red mouth, and penciled sloe eyes.

Anyway, I decided to try to become an Ikette if only to see how Tina could possibly make a “nice Jewish girl” into a flaming “Hot Mamma.” I finally got Ike and Tina to agree that I could be an “Ikette for a night” during their Las Vegas engagement. When I arrived from my home in New York at the Turners’ Bolic Sound Studios in Inglewood, California, I was told that Tina was home, exhausted from completing her role as the Acid Queen in Ken Russell’s movie Tommy and that Ike was “in seclusion.” What’s more, no one in the I.&T.T. organization had been informed of the advent of a white, Jewish, neophyte Ikette, and rehearsals were not set up. This was on Monday, and on Thursday we were due to perform in Galveston. Galveston? What happened to Las Vegas? I never did find out. Finally, Ester Jones, known as “Motha” Ikette and the group’s trainer, rounded up the other current girls. The Ikettes as of July, 1974, were as follows:

Marcy Thomas: A twenty-four-year-old Diana Ross type who is appreciated for her fast, filthy tongue, blond-streaked wigs, and taut bubble-ass. She says Ike “auditioned” her and promised her he’d “eventually” record her own LP. Marcy is a nonstop talker, with the subject matter centering on and about herself. She’s been with the act for six months, and the boys in the band give her four more months because of her “get stuffed” attitude. Marcy explains to me, “Look, man, face it, this act is ‘Marcy Thomas and the Ike and Tina Turner Revue.’” You have to admire Marcy’s supreme superiority complex in a company of gold-plated egos. Still, she’s one of the few Ike choices who can carry a tune.

Yolanda Goodwin: With the troupe six weeks when I arrived, she has the quiet beauty of a Gauguin Polynesian. Soft-spoken and naïve, twenty-one-year-old Yolanda is married, has a seven-month-old baby and was a bank teller when one of Ike’s secretaries told her about the weekly auditions. Ike did not try her out. Tina did and found her an “okay harmonizer.” However, the band gives her two weeks more because she’s “too stone-faced onstage” and “isn’t wild enough in the hips.” (The band underestimated the staying power of both Marcy and Yolanda, for they were still in the act as of last December and slated for the spring tour of Japan.) Meanwhile Yolanda lives in constant fear of Ike, but insists on staying on “’cause I have nowhere else to go and I need the exposure.”

Ester Jones: A professionally patient, warmhearted and pure-headed soul with a golden, rich voice. She copies Tina’s mannerisms, right down to the ring with “love” spelled out in diamonds and the large wrist-wide gold-chain watch, but is blacker in personality. Three years ago, Ester and Claudia Lennear and Edna Woods made up the best set of Ikettes, according to Tina. “Ester is the hardest worker and the toughest dancer,” says Tina. “There wasn’t a routine she couldn’t pick up in two seconds.” Ester is also responsible for much of the choreography. Ester told me that the Ikettes earn only one hundred dollars for two shows a night and they all have to bunk together in one room. “Listen, last year it was worse. We got eighty-five dollars a night, and in the beginning it was thirty-five.” Ikettes also must pay for their own shoes and are responsible for cleaning their own costumes. Ester quit momentarily when Ike once fined her fifteen dollars for being late onstage. (Ikette fines are famous, and they can range from twenty-five to one hundred dollars for such “inexcusables” as sloppily sewn hooks and eyes, snagged stockings, no toenail polish, talking too loud in hotel rooms late at night, tardy arrival at the airport, no-shows at rehearsals because of menstrual cramps. “Actually you can get fined for breathing if Ike decides he doesn’t like you or if he happens to be on a downer.”) Ester lives in southwest Los Angeles with her husband, while their three children live in Texas with her grandparents. “I sure as hell can’t fly them up here and support them with the bread I make.” Ester is in the studio three days a week but is never paid for auditions and rehearsals from four p.m. to six p.m. (singing) and then from six p.m. to ten p.m. (dancing) and sometimes ten p.m. till two a.m. for recording. “We only make money on the weekends, and with our usual fines that leaves me with a little more than two hundred dollars for three nights’ work.”

I explained to Ester, Marcy and Yolanda about my becoming an “Ikette for a night” and Marcy laughed. “And, girl, that’s about as long as you is gonna last.”

It took me two days, four hours a day, to learn the opening sixty-second theme. I arrived at Bolic Sound in my brown leotards and beige Guccis. Ester, Marcy and Yolanda were dressed in their red leotards and silver platforms. They took me through the paces for a rigorous forty-five minutes and then broke for ten. I never really caught on to the moves: couldn’t do the “Swim from the hip” and couldn’t karate-chop my arms tough enough.

On the second day, Marcy walked out of rehearsal in violet fumes, dismissing me as “the dumbest, stiffest chick I ever did see. You ain’t got nothin’. You can’t even move your hips. We go side to side and you keep doin’ that bump ’n’ grind. White girls can’t snap and jive. You keep doing all that cute soft shit. When we dance, man we’re sharp and we hit. You ain’t hittin’. . . . You is missin’.”

Frankly, I agreed with her.

But Ester kept after me and only cut her cool with laughter at my Jerry Lewis fallen-arch style of Ponying and my Jackie Gleason knee-flap version of the Frug. The routines were even faster than I had imagined (it’s not like boogying to the AM radio station in the privacy of your bathroom mirror), and I soon realized that if I didn’t move on the exact count I’d be trampled by Tina and the girls. Onstage, it’s everyone out for herself and no one is going to give you a clue or help you fake it. By Wednesday, I had it down, although Marcy became impossible and kept hassling over how she “couldn’t stand lookin’ at any of yus face no more.” Yolanda felt my voice was “so off” that she insisted I just lip sync and she’d sing louder. Ester understood where I was “coming from” and just worked on making sure I knew what direction to flail my arms and at what time I do “the Squat.”

Meanwhile, Tina was nowhere to be found. After three days of constant rehearsing, I finally got a call at one a.m. from Rhonda, the white, tight-lipped manageress, to say that Tina was rushed to the hospital with bleeding hemorrhoids. My heart skipped a beat. I had never considered hemorrhoids could be the end result of becoming an Ikette. Rhonda announced that the gig was off for the weekend. I sighed in relief at what Galveston had been spared. Rhonda added that we would definitely go on to Spokane the following Friday, and we should continue rehearsing. Ester kept on working with me, and I proceeded to get worse. We’d dance in one of the sound studios while the entire I.&T.T. company sat in the glass-enclosed, soundproof booth howling and imitating me, as I later learned. At the time, I was nearsighted and innocent enough to assume they were cheering me on.

It was during the second week that I noticed the tiny TV cameras and audio devices in each Bolic Sound room corner. I also noticed that Ester and the girls only spoke intimately to me in the toilet (where there weren’t any cameras or mikes) or on the street. Then I found out that Ike has the entire studio and his home monitored so he can sit in his apartment and watch and listen to his “kingdom.”

The Spokane weekend was approaching and Tina was still in the hospital. Spokane was canceled. Now we aimed for the next week in Tucson. At this point we could have played anywhere between Grossinger’s and the moon, and I couldn’t have cared less. I had about had it with Marcy’s mouth and Yolanda’s yelps of, “Why do we have to rehearse with her again? Let her fall on her face. She won’t get no fines.”

By the third week of rehearsals my Gucci shoe buckles had broken off, and I managed to demolish a pair of Florsheim sturdy oxfords. I was damned if I was going to trip on Ike’s gold shag rug one more time during the six sets of lunges I had to do in Higher, so I began attending the sessions in Adidas; nobody seemed to notice. By this time, Ester insisted I just do two songs and get off the stage. I wholeheartedly agreed, mainly because I knew of Ike’s reputation for changing the whole act instantly onstage. Rhonda was still keeping us on the cosmic hold button as to whether we were going to Spokane after all or maybe to Little Rock or nowhere at all. Then, a new problem developed. Ike was suffering from an eye infection and had to go into the hospital to get his pupil lanced. There went Spokane or Little Rock. I finally met Ike for the first time on the day after his operation, when I mustered up enough courage to go up to him in the hallway and introduce myself as “the fourth Ikette.” (People never introduce themselves in the I.&T.T. organization. Least of all to Ike. People walked around the studio for months unidentifiable to one another.) A deafening twenty-second silence followed as Ike raked my body with his one unbandaged eye and said impatiently under his breath, “Yeah, I know.” He immediately cold-shouldered past me and disappeared into the purple and black depths of his office. I wanted to follow up with, “Yes, you remember me. I’m the one who’s been starring on your monitor system from four p.m. to ten p.m. daily, Monday through Friday.”

We had reached the fourth week, and I had still not rehearsed with the band or with my five-pound wig and five-inch heels. Tina called me to apologize for the delay. “We’re finally off to Vancouver on Wednesday.” Vancouver? “We would have gone out last weekend even though I was hurtin’ soooo bad and I still am. Don’t tell Ike that though. But when he got stuck with his eye I got an extra week off. See, if we don’t sing we don’t eat. So we gotta go this Wednesday and we got to do two shows a night till Sunday. Oh, yeah, and we changed the act. Ester will have to teach you the new stuff. Sorry.” She’s sorry? It took me three weeks to learn six minutes; now I had two days in which to learn ten minutes.

With the date as firm as dates ever get in the I.&T.T. organization, we went to Tina’s home for a costume fitting. Actually my “fitting” consisted of trying on and galumphing about in Tina’s gold plastic platforms (she’s a size 8A and I’m a 9 ½ AAA), her gold-chain bra top (she’s a 34A and I’m a 36C), and her micro-mini jersey skirt (she’s a 24 waist, I’m a 32). She squinted at me for a while and finally sighed, “Oh, well, it’ll do.” She warned me that normally she would fine me a hundred and fifty dollars for looking that way onstage but since I’m only a “guest Ikette” it wouldn’t matter. “Fix those hooks and eyes and I’ll give you my briefs and panty hose, but I want them back when you’re done.” Returning used briefs and panty hose? This is a class act?

After the costume “fitting,” Tina taught me how to apply the three layers of “natural look” makeup—everything had the label “Deep Tan” on it—and insisted I wear her red wig. It took her a half hour to braid and bunch up my own hair. Apparently the braids make the wig adhere to the head better. She nailed the Mallomar mane to my scalp. In ten minutes I had a crashing headache, I went cross-eyed, and my eyes started to tear. It was then I realized that I could never make it as an Ikette. I was allergic to the prime performing prerequisite . . . THE WIG. Tina then lectured me about how she wanted me to grow out my own hair and that she herself would dye it coppertone.

“You’re such a lovely girl but you walk around looking like Phyllis Diller. Why don’t you get into yourself, girl . . . get into your sexuality.”

I left Tina dressed in her muffin slippers and white baggy sweat suit with a bandanna covering her corn-rowed almost hairless head (she never reveals her own hair to anyone since she lost most of it at the age of nineteen from dyeing it red), crouching on her hands and knees cleaning up the hairpins and dust on her rug. There was the real Tina Turner . . . getting into her own sexuality.

After the three-hour session, Ester suggested we go back to the studio and learn the new theme. Marcy started to balk in the Turners’ driveway. She didn’t want to rehearse because of menstrual cramps. Ester pointed out that cramps were not an “acceptable excuse.” Before we knew it we had a rip-roaring rumble between the two of them. It continued throughout the drive to the studio, where the two proceeded to go at each other tooth and nail in Ike’s private sound booth. Ike secretly turned on the mike so that everyone could hear the two girls calling each other “you black bitch,” “you wide-nosed coon,” etc. Ike finally came in and broke it up. Ester was left with a bleeding upper arm, and Marcy had a black-and-blue lower jaw. Ironically, the fight began moments after Tina explained to me how “personally solid” and what a “tight-knit family” the group was. “Everyone’s sign is compatible you know . . . all Scorpios and Sagittarians. It’s why Ike renamed the band the Family Vibes.” Later Ester added, “That’s bullshit, man. We haven’t had a close-knit group in five years. As for the Ikettes, we all hate each other and operate on raging competition.” As a result of all this close-knit hatred, rehearsals were called off because Ester had to go to the clinic for rabies tests. So much for my learning the ten minutes in two days.

That night Tina called me to talk about the fines and the Ikette etiquette. “I know it sounds awful but that’s the only way we find to get the cooperation and the results from the girls. Most of them have never performed before and they simply don’t know. But it’s no excuse. They gotta learn sometime. And, believe me, we all had to pay our dues in the business. I’d still be pickin’ cotton in Tennessee if I hadn’t paid my dues and served Ike. But the secret to being a successful Ikette has more to do with the voice than the feet. Remember that.” She didn’t know I was lip syncing the show. “I also believe in the Ikette visual. I don’t see it as cheap or vulgar. Nor do I see myself as that. Sex is not cheap or vulgar. And I always loved the look of long straight hair. Ike says he patterned me after Sheena of the jungle. She was white, you know. But I still love the look and action of long hair movin’ and the short skirts shimmying. I want action on that stage at all times. So whenever you don’t know what to do just shake your wig and swim with your arms. But don’t ever ever crack up onstage.” Obviously Tina was giving me a preview of the “George Allen” pep talk she gives the Ikettes before they go onstage. By the end of it she was hoarse from making her points. “But if ever I see a wig start sliding or even a boob slip out of a bodice, I’ll slap a fine on the girl. I mean, why shouldn’t I? They represent me, and in my act they gotta look outa sight at all times. There’s simply no room for sloppiness and unprofessionalism.” I always wondered what being “unprofessional” meant. Now I know that being “unprofessional” is slipping wigs and sliding boobs.

Wednesday morning arrived, and I was on the plane at 8:15 a.m. The rest of the I.&T.T. crew ambled to the gate at 8:32 for the 8:35 takeoff. They also went through their own customs check while I went through the gates with the rest of the civilians.

We checked into the hotel and I had to share a room with Yolanda, who had pinkeye. When I explained to her that she must use a separate towel and bar of soap, she iced up and accused me of being prejudiced and “just like all those jive liberals.” I ended up moving into my own suite, while Yolanda insisted on sleeping on a rollaway with Ester and Marcy. As for the other arrangements, I learned Ike always rents a suite of rooms for himself, a separate suite for Tina, and a party room. The party room is for post-show use by the crew, although Tina never shows. The Turner groupies, however, are present in full force. And they are a definite type: they all seem to be white, fifteen-year-old lobby loiterers with orange hair and blackheads. The band and Ike have all the fringe benefits on the road, while Tina’s life is regimented to knocking herself out at show time and then rolling up her wig at the completion and going to bed. The woman leads two totally separate lives. “I call my stage self ‘Tina Turner’ and my real self ‘Anna Mae Bullock’ [her maiden name].” The Ikettes rarely mix sex and show on the road. There is no intramural sex with the band members, and the girls rarely go out looking for action. Possibly because they’d get fined if they did.

Wednesday afternoon Tina warned us to get plenty of rest and to eat before the show. She herself never drinks or smokes and will have nothing to do with drugs. Her addictions are Preparation H and Geritol.

Show time crept up and at six p.m. we drove over to Baceda’s nightclub, a dinky roadhouse which houses two tiny stages and a spaghetti-and-beer restaurant. The stage was as big as a tongue, and Ike threw a fit when he saw the basement dressing room: the classic setting, with one dangling bare bulb and a single clothes rack for the costumes, no mirrors, and some leftover French fries sprayed along the linoleum floor. Since I still didn’t know the theme, Ester quickly verbalized the routine (“You lunge four, then slide two, then boogie for eight, on ten you Pony over to Tina”) while Tina corn-rowed my hair. Mumbling Ester’s instructions to myself, I put on my costume. Suddenly Tina was yelling at me about torn hooks and eyes and said that I would start with a fifteen-dollar fine. I would have found this amusing if her yelling hadn’t made me forget what I was supposed to go on the stage and do in order to get the fine in the first place. I complained to Ester, “How can you people operate this way? Marcy and Yolanda don’t know the new act either and where is all this ‘pro know-how?’” Ester just sighed and broke into one of her wide-angle grins. “You gotta get into B.M.T.” “What’s B.M.T.?” “That’s Black Man’s Thinking.” I had twenty minutes left, so I stood in front of Ester’s tiny round hand mirror for the before-stage Ikette check. I tried to toss my weighted-down head in a sexy manner, and it felt like my eyes were about to explode out of their sockets. My nose had started running from my wig allergy. The ankle straps of Tina’s tiny shoes had cut off my circulation from ankle to hip. Tina told me to bend over and shimmy a few times to check for peekaboo boobs. Nothing peeked or booed (yet). We were ready to go. As I hobbled out of the dressing room, some polyester-suited man stopped me and asked if I was a transvestite. He hit the nail on the head.

The witching hour was close. The Family Vibes had played for forty-five minutes. And before I knew it we were announced. “And here are those lovely ladies we’ve all been waiting for. Come on, people, let’s get it onnnnn down and dirty for the I-I-I-kettes.” It seemed as if he trailed that “I” for about two hours. We shuffled onstage and immediately I felt the Vancouver frigidity. No handclaps . . . no out-of-control enthusiasm. I faked my typical messy Mashed Potato, waiting for Ike to give us some cue as to what the song would be (as if I knew what to do once he played it). It didn’t take long for me to sink into incredible self-consciousness. I was the biggest person onstage: Tina and the Ikettes average five feet, four inches, and the shoes rounded me up to a neat six feet. The stage became as big as my instep, and I looked like a brontosaurus and felt like Alice in Wonderland after she ate the “tall” cookie. All this and the wig threw my timing off. The lights felt like a microwave oven, and I ended up squinting instead of smiling or looking sexy whenever I lifted my head. Within seconds my wig fell forward, blinding my view almost entirely. So it now looked like the Ikettes and something from the goon squad on the end. Ike started the new theme, which was Ringo’s Oh My My. Since I didn’t know the lyrics, my mouthing wasn’t in sync, but at least my lips were moving. All the while I had to keep my head tilted forward because the wig was inching its way down my spine. I thought I recognized an old schoolmate in the front row and almost tripped on the cymbals when I tried to dance out close to examine her. At least I knew how to grab the mike and when to squeeze the girls’ waists during the chorus of “Oh my my/Oh my my/you can boogie/if you try.” I was trying, but maybe too much. My mouth freeze-dried into a sickly grin, my wig was now down to my chin and suddenly Tina made her entrance screaming, “Hiiiii everybody.” She squealed and squawked her song and stood spread-legged in front of me (at least I think she was in front of me) and all I could see of her was a flash of red sequins, a lot of bare back, and a pyramid of auburn hair. Seconds later, Ester and Marcy were scattered about the stage looking like they knew where they were going, and I was left standing in front of Tina (an automatic fine). Tina then pushed me stage left with her hip swings, and I was left clutching the curtain and using it to wipe my running nose till the third “Oh my my” refrain. Eventually I tried to Pony out center stage and suddenly felt my ankle give and in one eyeblink’s time I found myself on one knee with one breast about to bust through the chain halter. Now what does one do when one finds oneself as an Ikette on one knee in the middle of a go-go rendition of Oh My My while everyone else is madly “hunching” about? I did the natural thing. I broke into Swannee with all the right Jolson arm extensions. After which I half stumbled, half boogied off the stage. And would you believe Ike and Tina didn’t yell at me, although they did fine Yolanda for being too serious onstage. As for me, I sat in the dressing room exhilarated at my debut and crying because I couldn’t get the wig off and it was suffocating. Afterward, I went up to Tina and asked her what she thought. “You did just fine, girl. As good as any of them on their first night. But you do a terrible Jolson.” (Two days later Ester sent me a review of our opening night that appeared in The Vancouver Sun. Critic Scott Macrae wrote that “the Ikettes are a delight. Even if sometimes the one on the left doesn’t know what the one on the right is doing.”) But the finale came when I approached Ike for his final approval. I wanted him to make it official and pronounce me “Ikette for a night.” He sat sulking in the dressing room, banging his Sony tape deck on the makeup table in post-show rage. But when I asked him, he stopped in a frozen stance and stared at me with his big black eight-ball eyes. He stood up slowly and dug his silver-booted toes into the linoleum. All eyes were on Ike and he couldn’t stand being the center of attention so he acted like a trapped wild animal. We all held our breath and waited for his comment. In that heavy voice and with the first wide quivering smile I ever saw him crack he belched: “Don’ mean shit.”

Now what he meant by that remark I really didn’t stay to ask or analyze.

Get instant access to 85+ years of Esquire. Subscribe Now! Exclusive & Unlimited access to Esquire Classic - The Official Esquire Archive

- Every issue Esquire has ever published, since 1933

- Every timeless feature, profile, interview, novella - even the ads!

- 85+ Years of outstanding fiction from world-renowned authors

- More than 150,000 Images — beautiful High-Resolution photography, zoom into every page

- Unlimited Search and Browse

- Bookmark all your favorites into custom Collections

- Enjoy on Desktop, Tablet, and Mobile