When will the movies learn not to adapt great, or even good, novels to the screen? This is not the place to debate into which of those categories The Great Gatsby falls; either way, it is a work of art because of its style, and there is no way in which a written style can be turned into a cinematic one. Partly out of exploitativeness, but partly also out of stupidity, producers ignore a fact that the very schoolchildren of today have mastered: the form is the content.

The shape of the novel on the page, its paragraph and sentence structure, the imagery and cadences of the prose, and all the things that are left to the imagination, these, as much as plot and character, are what the novel is about, and these, in good and great novels, cannot be transposed on screen—do not even yield cinematic equivalents.

To a short, sleek novel like Gatsby, where the slight action moves forward like a capricious swimmer (now at a leisurely breaststroke, then at a furious crawl, then again with a dainty backstroke or a splashily showy butterfly, but always cool and elegant) nothing could be more destructive than the slow pace and top-heavy lavishness and overexplicitness. Under these, the film version sinks to the bottom.

Yet even if the film were paced better—and it is about to receive some postmortem cutting—it would be no use. Much, if not most, of the book’s life is in the descriptions and animadversions of Nick Carraway, the naïve yet thoughtful narrator, whose gradually waning starry-eyedness and nascent sobriety provide the basic flavor and progression. But even though Francis Ford Coppola’s screenplay incorporates some of this as Nick’s voice-over narration, indeed smuggles some of it into the dialogue, a great deal of it inevitably gets dropped. The unfortunate attempt has been made, however, to translate almost every missing textual element into a compensatory silence, a lingering over something, a marking of time, and it is often as if the screen were invaded by visible lacunae and hiatuses slouching and dragging themselves about among the performers.

There are no fewer errors of sheer incomprehension. Take, for example, the case of a single line. In the book, Nick says of Daisy, “She’s got an indiscreet voice,” and breaks off hesitantly after, “It’s full of—” to which Gatsby responds suddenly (as Fitzgerald states) with, “Her voice is full of money.” Jack Clayton, the director, allows Robert Redford’s Gatsby to be method-actorishly introverted and speculative: “It’s full of . . . full of . . . the voice is full of money.” How deeply wrong those pauses are! Gatsby is not an analytical, philosophical soul; if he were, he wouldn’t be Gatsby. His rare insights, and this is one of them, are slapdash and almost fortuitous, which is what makes them so touching and even tragic: they are truths from the mouths of babes who should long since have grown up; and, like other such truths, they go by ignored, first and foremost by the babes themselves.

Or take a short scene. Gatsby, followed by Nick, is showing Daisy his house and riches for the first time. As Fitzgerald puts it, “He took out a pile of shirts and began throwing them, one by one, before us, shirts of sheer linen and thick silk and fine flannel, which lost their folds as they fell and covered the table in many-colored disarray.” The “soft rich heap [mounts] higher” and Daisy bends into it and cries “stormily,” explaining between sobs: “It makes me sad because I’ve never seen such—such beautiful shirts before.” Now Clayton and Coppola, presumably to make the scene more dramatic, have Gatsby toss out shirts ever more frantically, not really on the table before Daisy, but all around on the floor. The meaning is thrown away with the shirts: what is intended as an awkward, foolish love tribute, a wooing of Daisy with these absurd yet to her not at all irrelevant trappings, becomes in the film an act of display for its own sake, a pointless frenzy of excess. And when the inept Mia Farrow then starts sniffling and simpering, instead of crying stormily, we do not get that sense of heartrending preposterousness, of too much not soon enough, of lives wrecked for the want of a hundred silken shirts. The audience, both times I saw the movie, merely laughed. They should have laughed and wept.

Clayton’s and Coppola’s directorial and scenaristic faults, despite, and even because of, superficial striving for fidelity, are legion. It is a big mistake to introduce many of the same characters during both big-party scenes at Gatsby’s house and so convey a certain consistency and stability where all should be flux and transience. It is an error to belabor the T. J. Eckleburg sign more than Fitzgerald did, clobbering us with what should be a symbol only for the pathetic Wilson, and certainly not appear to be some God-oriented moral message of the entire work. It is a dreadful idea to have the bereaved Wilson consoled by an elderly, almost slow-witted comforter (unsubtly played by Elliot Sullivan), when Fitzgerald deliberately made the character young and not semi-doddering—to show that not even the young and strong can help one another in a world grown senile around them.

There are many such lapses, most of them on the side of simplification or obviousness. Others, though, derive merely from the pitfalls inherent in the transferal of genres. Personally, I would be happier if neither novel nor film contained that supererogatory, quasi-poetic ending about America having loomed as the last great promise to its discoverers, but that Gatsby and his likes failed to realize that the dream was already behind them. Yet under no circumstances should part of this commentary be distributed as dialogue between Nick and Gatsby: it is bad enough for the author to be overexplanatory, but unforgivable for a character to know what he cannot know. After such knowledge, what forgiveness?

Then there is the wretched cinematography of Douglas Slocombe. His colors are often those of primitive Twenties postcards, faces in a sunset, for instance, doused with a flat orange-yellow light coming from the wrong direction! Everything in the picture gleams and glistens, or else dreamily blurs; but when, in close-ups, human eyeballs begin to sparkle like Christmas-tree ornaments, we suffocate in all that pomp and zirconstance.

The acting and casting also deserve castigation. Redford cuts too elegant, civilized, almost overeducated a figure to convey the fishily and insecurely risen Gatsby; conversely, Bruce Dern is too crude and oafish to be a born and Yale-bred millionaire: he, not Gatsby, emerges as the outsider. Mia Farrow, whose voice is all crooning and squawking, embodies Daisy’s superficiality, but not her charm and attraction. Ironically, her skull-like face looks much too unhealthy to suggest carefreeness careering into carelessness. Karen Black is miles away from Fitzgerald’s Myrtle; no simple, totally sensual older woman, she is merely a grosser version of Farrow’s insipid sex kitten. Miss Black’s histrionic range is not just limited—it seems actually to shrink with every new picture. Scott Wilson’s Wilson is too weak and hysterical from the outset, but Lois Chiles makes an acceptable Jordan Baker, and Roberts Blossom a believable Gatz Sr.

Sam Waterston, who specializes in good-natured dopeyness whether or not his part calls for it, is perfectly cast as Nick and comes off much the best. But to turn The Great Gatsby, nervous and rapid, into a slow, uninvolving “The Good Carraway,” is seedy business indeed. I doubt if the novel ever bored anyone; at the end of the film’s one big pre-opening screening there was only dull, exhausted silence. Not even the freeloaders and sycophants could work up the energy to applaud.

Some directors spring full-fledged from Jupiter’s brow—indeed film, I for such a complicated art, is remarkably rich in practitioners whose first works were technically and artistically commanding. That is not the case, however, of Maximilian Schell, the accomplished screen and stage actor who has been gradually evolving into a film maker. His first movie, an adaptation of Kafka’s The Castle, he merely produced; the next, First Love, based on Turgenev’s novel, he co-scripted and directed. Apparent in this film were culture and literacy, but also overeagerness, overambitiousness, the need to cram the film full of “Art.”

Wisely, Schell had engaged Sven Nykvist, Bergman’s superb cinematographer, and together they set about making a movie as rich in colors as the story is in the hopes and pangs of first love. They succeeded too well, producing a surfeit of gorgeousness beyond the digestive power of two fragile human eyes. Other things went wrong, too, not least a corollary crowding in of incident, some of it too obliquely and allusively presented, and the faulty or altogether lacking rhythm in the film’s unfurling. Some of these difficulties persist in Schell’s new picture, The Pedestrian; some of them have been overcome, but often at the cost of new ones. Still, the film is markedly superior to its predecessor: a worthy failure. But failure all the same, as proved to me by the fact that it gets worse on second seeing. A good film holds its own on renewed exposure, and a great one gets better with each return visit.

Schell is not fond of linear narrative and, accordingly, the film is loosely strung together, full of flashbacks to the same scene but with a difference, flash-asides to what might be happening but isn’t, extreme close-ups in soft focus for visual dépaysement, omission of establishing shots so that we must unscramble both time and place. Such stratagems are in themselves neither good nor bad (although much contemporary film criticism esteems them for their mere existence), but rather like parentheses, ellipses, aposiopeses in writing—good if put to good use, bad if misused. In The Pedestrian there are examples of both.

What plot there is concerns a German industrialist, Giese, who was present as a German officer at a massacre of Greek women and children during World War II. His exact role in this inhuman reprisal is unclear. An unscrupulous newspaper editor, Hartmann, digs up some facts, among them the existence of a female survivor of the holocaust, the identity of another now solid burgher involved in the mass shooting, and the possible connection between this and the recent death of Giese’s elder son and heir, Andreas, during a shadowy auto accident while Giese was driving. The film follows the final stages of the paper’s investigative operations, and the movements of Giese himself, spied on by reporters. The tycoon’s day proceeds from a visit of the old man and his grandson to a science museum, thence to Giese’s unexpected dropping in on his young mistress whom he catches or almost catches in flagrante delicto with a young man, then on to a compulsory illustrated lecture for automotive delinquents, then to a trolley ride during which the old Greek woman observes Giese but cannot positively identify him, and, further, to a return home and his unsympathetic dropout of a younger son, his patient, forbearing wife, and some confrontations with the prying reporters.

There are numerous other scenes, including such curious set pieces as a dream of Andreas about death, which provides a kind of leitmotiv—far from fully integrated into the film, however; a dialogue with the grandson about the meaning of history, which never makes the pregnant pronouncement on whose verge it hovers; a scene in which seven old women, including Giese’s mother and other relatives and friends, discuss the nature and morality of war; a flashback in which Giese, vacationing in Greece with his mistress, is reluctantly persuaded by her to join in a folk dance under the suspicious eyes of the natives; and another, matching scene, narrated but not shown, in which a similar event took place in a Spanish flamenco joint, but this time on a trip Giese took with his wife.

One problem with all this is the overabundance of literary and cinematic influences. The way in which the opening dream is photographed derives too obviously from the beginning of Hiroshima, Mon Amour, with the camera hugging an unidentifiable object so tightly and blurrily that it looks mysterious, otherworldly, downright metaphysical. Meanwhile the voice-over narration of the dream’s content sounds like a cross between a Kafka parable and an early Rilke story. Even when we figure out what is going on, we cannot relate it to the rest of the film. Again, a bedtime story Giese tells his grandson seems too heavily indebted to the old woman’s tragic fairy tale in Büchner’s Woyzeck, and strikes a tone inconsistent with Giese’s other talks with his grandchild. The scene in which an aged actor and actress recite the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet, as they once long ago acted it on the stage, fills me with an uncomfortable sense of déjà vu, although I cannot actually trace its derivation.

Other scenes suffer from excessive staginess. There is something de trop about dredging up a handful of famous old actresses from all over—including Germany’s Lil Dagover, Austria’s Elisabeth Bergner, England’s Peggy Ashcroft, France’s Françoise Rosay, and several others scarcely less celebrated—and seating them at a round table to discuss war. It is hard to make them appear to belong there, and the grand manner in which they act betrays them as prima donnas preserved in their pride. It is all too good to be true. Still other scenes belabor an obvious irony, as when a little girl runs from one side of a street to the other to push a pedestrian’s button, and at the mischievous brat’s interminable red light the whole law-abiding German economic miracle seems to come to an obedient standstill.

The little girl is a pedestrian, and pedestrians in this film are privileged beings. Giese, because his driver’s license has been temporarily revoked, has become a pedestrian, too, and makes discoveries that as a driver he would have zoomed past unseeing. There is the realization that his mistress cheats on him, and that there is a whole world of trolley riders, initiates in a mystery of the impecunious about which he knows nothing. As a pedestrian, too, he is confronted with the horrible images of vehicular homicide, which put him in touch with the truth of Andreas’ death: his son was trying to kill both of them in a crash after learning about Giese’s war guilt. The truth, then—but does it bring happiness, or even peace?

This might well have been the theme of the film; instead, it keeps getting sidetracked and hopping all over the place. The device of incremental repetition—flashbacks telling a little more each time—is indulged in both in the car-crash episodes and in that of the massacre, and begins to look gimmicky. The metaphysical issue—What is death? —keeps popping up in various guises, yet remains as unintegrated as it is unresolved. The grandson’s questions—“What is history?” “Where is daddy now?” “Is daddy’s death part of history?”—are not made germane to the master themes of truth and guilt. There are beautiful moments, like a tracking shot of Giese walking past the Krupp Works that finally makes no point; Godard notwithstanding, a tracking shot is not ipso facto a moral choice. Other shots are held too long, like the darkening image at the end of the Greek-dancing sequence, or the film’s closing shot with the camera pulling back to reveal a heated debate as having been no more than a TV panel show. A Viennese waltz inundates us, the formerly furibund panelists shake hands, and the camera loses itself in surveying the television equipment.

There are even graver lapses, like a sentimental flashback to Andreas, his wife and child playing in a blissful landscape while the death of Greek children is discussed on the sound track in facile irony. But the film has its virtues, too, in Schell’s skillful writing and directing of certain vignettes. Thus the relationship of Giese and his mistress tells itself by nice indirections; his relation with his wife is sympathetically developed in a few swift scenes; the television debate, largely improvised, achieves considerable power through eloquent spokesmen on both sides. The cinematography by Wolfgang Treu and Klaus Koenig is effective throughout, but downright breathtaking in certain snowscapes—how photogenic the color white is when shot on color film! Dagmar Hirtz, who charmingly plays the small part of Andreas’ wife, has edited the film sensitively, and the excessively slow fades doubtless represent the director’s wishes.

Much of the acting is excellent, owing in part to Schell’s clever intermingling of amateurs, professionals, and displaced professionals; thus the unsavory Hartmann is played by the English stage and screen director Peter Hall, and Giese himself by Gustav Rudolf Sellner, a stage and opera director. The results are interesting: from the directors one gets a more cerebral kind of acting than from the actors, from the amateurs something more spontaneous, and so a whole spectrum is established. Still, The Pedestrian remains a disjointed movie, with moments of pretentiousness, exaggerated improbabilities, and too many questions raised. Granted, an artist is not obliged to answer questions, but he must shed light by asking them more clearly.

Yet Schell, at least, is not afraid of engaging serious subjects, and does not become so absorbed in their seriousness as to forget the free play of the style-giving imagination. He does not, generally, allow importance to evaporate into slickness or ossify into ponderousness. The German film entered the postwar years with a distinct promise in the works of Helmut Käutner, Wolfgang Staudte, Bernhard Wicki, and a few others, a promise that was completely derailed in the hands of such overcerebral or simply unhinged experimentalists as Alexander Kluge, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Werner Herzog, and Jean-Marie Straub. It would be nice to hope that Maximilian Schell might contribute to recouping its flagging fortunes.

Get instant access to 85+ years of Esquire. Subscribe Now! Exclusive & Unlimited access to Esquire Classic - The Official Esquire Archive

- Every issue Esquire has ever published, since 1933

- Every timeless feature, profile, interview, novella - even the ads!

- 85+ Years of outstanding fiction from world-renowned authors

- More than 150,000 Images — beautiful High-Resolution photography, zoom into every page

- Unlimited Search and Browse

- Bookmark all your favorites into custom Collections

- Enjoy on Desktop, Tablet, and Mobile

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Articles

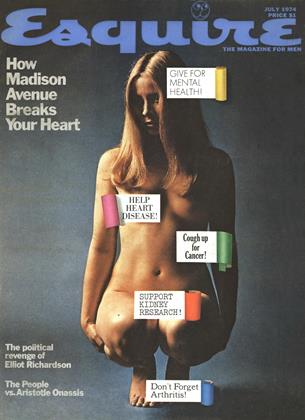

ArticlesThe Smile on the Face of Elliot Richardson

July 1974 By Tad Szulc -

Articles

ArticlesThe Score From New Hampshire: Democracy 1, Aristotle Onassis 0

July 1974 By Gerry Nadel -

Articles

ArticlesFixing Things: A Guide for the Bewildered

July 1974 By Bill Elisburg -

Articles

ArticlesWhat’s Wrong with This Picture?

July 1974 By Arthur Miller -

SUMMER SUPPLEMENT

SUMMER SUPPLEMENTOptional Excursion: A One-Way Ticket to New Zealand

July 1974 By Richard Joseph -

FICTION

FICTIONA Game Without Children

July 1974 By Rick DeMarinis