LETTER FROM EUROPE

AUBERON WAUGH

President Nixon’s threat, that America and Europe must “go separately” if Europe is not prepared to be more cooperative about United States policy in the Middle East, has caused a certain amount of merriment over here. America’s option of withdrawing troops from Europe was always implicit in the relationship between the two continents, and underlies many of the more extravagant declarations of affection and gratitude which public men in Europe sometimes feel it prudent to make. However, now this subtle and delicate relationship has been spelled out in the baldest terms and in the form of a threat, the total effect is rather comical. Mr. Nixon is seen as the aging, rather fat wife who threatens to withdraw her marital favors after thirty years of marriage if her husband does not mend his ways. What must we do to restore tranquillity in the home?

A far more significant part of Mr. Nixon’s Chicago speech came where he seemed to be expressing resentment for the first time against the Common Market’s protective trade system: “It is essential that we get what I would say is a fair break for our producers.” If this is to be a permanent feature of the scene, then the prospects for U.S.-European relations must look extremely bleak, already soured by suspicion of Mr. Nixon’s policy of détente with Soviet Russia, by the oil problem, and by a general, semi-articulate feeling that the inflation of currencies we are all suffering from owes more to Mr. Nixon’s decision to end the gold-convertibility of the dollar than it does to any genuine world shortage of commodities.

But it might be as well to look at the Common Market institutions which are now seen as a threat. The European Parliament at Strasbourg has been put in a curious state as the result of the British election. Mr. Harold Wilson’s Labour Party, which just won the election, although without a clear majority and polling fewer votes than its main opponent, has refused to send any M.P.’s to Strasbourg. The Conservatives are unwilling to reduce their parliamentary strength by sending any more, so the U.K. delegation now includes four former Conservative M.P.’s who have lost or given up their seats, and eight peers, or members of the House of Lords, who have never been elected at all. This has rather upset the Europeans. Mr. Schelto Patijn, a member of the Dutch parliament, explained it thus: “No other country sends nonrepresentative members like the British peers. When they start speaking, we stop listening.” All of which might rather depress his colleagues from the United Kingdom, if it were not for the generous living allowances and delicious food of Strasbourg, home of pâté de foie gras and the even more seductive foie de canard chaud aux raisins. Poor Mr. Patijn is off on

a tour of the nine European capitals to urge the case for direct elections to the European Parliament, but does not expect to achieve anything within ten years. Meanwhile, there have been allegations that many European M.P.’s are fiddling their expense accounts and drawing the $62.17 daily allowance without attending the daily bore-in. This has caused even more consternation among the gourmands of Strasbourg.

The results of the election left Britain exhilarated but a little fearful. French friends express their sympathy, but on a trip to Amsterdam your European correspondent found Britain held in the highest esteem, even the subject of envy. With a powerless government and a hopelessly discredited opposition, we seem to have achieved the perfect mean. Nobody in Britain is particularly anxious to face up to whatever serious problems may be round the corner, and the inconclusive result gave us yet another breathing space.

For a few days after the election, we wondered about the fate of Mr. Heath’s Central Policy Review Staff under the leadership of Lord Rothschild, head of the English branch of the banking family and an expert, in his own right, on the behavior of spermatozoa. This body referred to itself as the Think Tank, and became known in Whitehall, less respectfully, as the Wank Tank, in acknowledgment of Lord Rothschild’s scientific training. It was charged with warning the Prime Minister in advance about such matters as fuel and energy crises. Yet Mr. Heath professed himself totally surprised when Arab countries quadrupled the price of oil, and took the country into the election with a record annual trade deficit of two and a third billion pounds (almost six billion dollars) even before the effect of the new price of oil had begun to be felt. That is one of the problems which nobody in England particularly wishes to tackle—the deficit for this year is estimated at between five and six billion pounds (between eleven and a quarter and thirteen and a half billion dollars), and somebody is going to have to lend it to us.

Another problem is that the British government is now less powerful than the trade unions. In fact the coal miners used conventional means to bring Mr. Heath’s Conservative government down, but they could equally have ignored parliament altogether, and destroyed its pay policy and union legislation by the simple expedient of not working. For a time, the union leaders seem to be happy. They dictated Labour’s election prospectus and told the new Chancellor, Mr. Denis Healey, what he must put in his budget—more public spending, a wealth tax, a higher rate of tax for higher wage earners, and no control of wages at all. But the time will come when they are confronted with the disastrous results of their own

policies, and nobody has any idea what will happen then.

Those who preach the inevitability of a military coup in Britain were encouraged by the Portuguese example. After one false start, when a few army units appear to have gotten the date wrong, General Spinola carried off the first effective change of government in Portugal in forty-two years with very little bloodshed. Although the apparent reason for the coup was Portugal’s African commitment, which has been bleeding the country white for twenty years, the more immediate reason for its success was almost certainly the rise in world commodity prices, which has shaken every Western political system and had knocked Portugal’s delicately balanced economy for six. At the moment of writing, it looks as if Spinola is pursuing a Portuguese version of Mao’s “Hundred Flowers” policy: from somewhere a Socialist party has emerged to press for free trade unions, diplomatic relations with Eastern Europe, among other absurd and extravagant demands. Fellow Europeans wait to see how long it is before General Spinola starts chopping off the heads in his garden, like Mao Tse-tung and Tarquinius Superbus before him. Revolutionaries might find even more inspiration from the Spanish example, where efforts by Basque Nationalists to blow up the Spanish Prime Minister were such a spectacular success that his car flew over a roof to land upside down on the first-floor balcony of a courtyard. The Spanish government’s reaction has been to reintroduce the garrote for executing criminals—an iron collar which snaps the backbone as it is tightened around the neck. Relatives of the two men garroted were invited to be present to see that the execution was done properly.

No newsletter would be complete without an announcement of a new government in Italy. The latest is the thirty-sixth since the war, and most Italians I have spoken to seem to agree that Signor Rumor is back again although I have heard other names suggested for the current Prime Minister. But nobody pays much attention to these things anymore in Rome, so they can scarcely expect foreigners to take an interest. In Paris, Pompidou’s death was long awaited and many French friends remain convinced that he had been dead for thirteen days before the sad announcement was made, rather than for the thirteen hours generally considered necessary to remove documents, tapes, et cetera, from the Elysée Palace on these mournful occasions. For many weeks after his death Parisians were intolerably jittery about the specter of a left-wing government, trying to unload mountains of francs on any foreigner passing through. They seem to have settled down again now.

In Italy, nightclubs and cinemas must

still close early, but motoring is allowed on alternate Sundays according to the car’s odd or even number. In Britain there was a deliriously absurd period in the run-up to the election when the miners were on strike and everybody was urged to share his bath with someone else in order to save fuel. Now everything is back to normal except the price of petrol, which seems to have settled at about $1.20 a gallon—in France, it is much more.

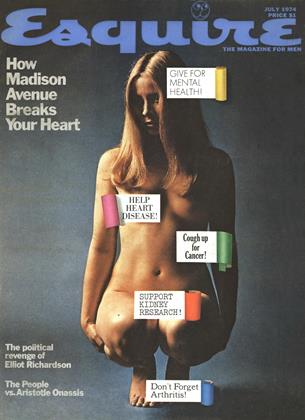

Get instant access to 85+ years of Esquire. Subscribe Now! Exclusive & Unlimited access to Esquire Classic - The Official Esquire Archive

- Every issue Esquire has ever published, since 1933

- Every timeless feature, profile, interview, novella - even the ads!

- 85+ Years of outstanding fiction from world-renowned authors

- More than 150,000 Images — beautiful High-Resolution photography, zoom into every page

- Unlimited Search and Browse

- Bookmark all your favorites into custom Collections

- Enjoy on Desktop, Tablet, and Mobile

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Articles

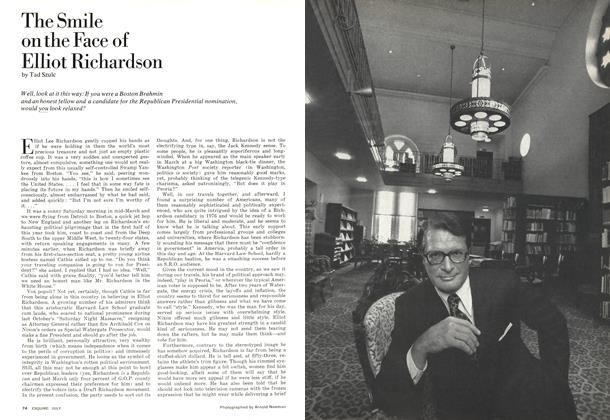

ArticlesThe Smile on the Face of Elliot Richardson

July 1974 By Tad Szulc -

Articles

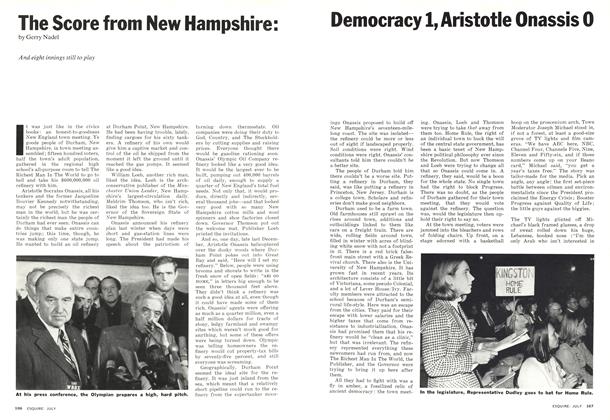

ArticlesThe Score From New Hampshire: Democracy 1, Aristotle Onassis 0

July 1974 By Gerry Nadel -

Articles

ArticlesFixing Things: A Guide for the Bewildered

July 1974 By Bill Elisburg -

Articles

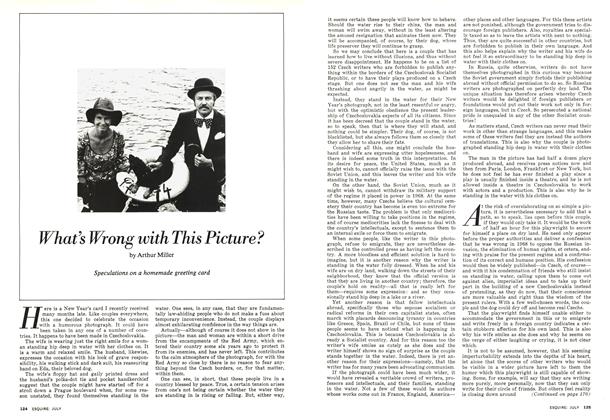

ArticlesWhat’s Wrong with This Picture?

July 1974 By Arthur Miller -

SUMMER SUPPLEMENT

SUMMER SUPPLEMENTOptional Excursion: A One-Way Ticket to New Zealand

July 1974 By Richard Joseph -

FICTION

FICTIONA Game Without Children

July 1974 By Rick DeMarinis