TRAVEL NOTES

RICHARD JOSEPH

Flying across the Pacific to research A One-way Ticket to New Zealand, the piece on Americans living in New Zealand which you’ll find starting on page 98, I may just have happened upon the secret of eternal youth. Your age depends on how many birthdays you’ve had, right? So if you don’t have any more birthdays, you shouldn’t get any older. Well, my Air New Zealand flight left Los Angeles at eight o’clock on the night before my last birthday, but by the time the DC-10 landed in Auckland the following morning we had flown over the International Date Line, so it was two days later. My birthday just never turned up. I got the day back when I crossed the International Date Line again on the return flight, but it wasn’t my birthday; so for the next year I’ll be no older than I was last year, and if I can arrange to do this annually I can be forever thirty-nine.

And New Zealand wouldn’t be a* bad place to visit every year. As you can see from the life-styles the American settlers outline for you in A One-way Ticket to New Zealand, the country offers great opportunities for escape—into the outdoors, if that’s what you like, or just away from pressure, if that’s what’s bothering you. The escape can be short term, of course; to enjoy a vacation trip to New Zealand you certainly don’t have to be thinking about settling there. Conversely, though, you surely shouldn’t consider emigrating to New Zealand without a long and careful look at what it has to offer and what it hasn’t. Tour operators and the airlines flying to New Zealand from the United States—Air New Zealand, Pan American and U.T.A.—have put together a number of tour packages well suited to both purposes.

Air New Zealand, for instance, offers something they call Freewheeler Holidays, featuring self-drive cars, thus enabling you to spend just about as much time as you choose at the places that most interest you. Included in the package are round-trip economy-class individual inclusive tour fare from Los Angeles, San Francisco, Portland or Seattle to Auckland, on New Zealand’s North Island; Avis rental cars with unlimited mileage and multiple hiring (picking up and returning cars at will along your route) ; and fourteen nights’ accommodation at motels or hotels with Continental breakfast.

The price runs from $1,003 to $1,125, depending on the type of accommodation you choose, based on double occupancy of hotel rooms. Single-occupancy surcharges and daily extension charges, if you wish to prolong your visit, are reasonable. (Note: Air fares and tour rates these days are in a state of what can charitably be called flux, but these prices were in effect at press time. In any case, they represent a good buy. The regular 14-to-28-day economy air fare between Los Angeles and Auckland is currently $962.90—only about $42 less than the minimum price of the whole package.) And you can, of course, combine your New Zealand visit with trips to Australia and the South Pacific: New Guinea, Fiji, Samoa, Tahiti—the whole wonderful scene.

And once you get to New Zealand, you’ll find the price level comforting-

ly low. While New Zealand has had its own brand of inflation, the bite hasn’t been nearly as sharp as ours. I’d guesstimate the general price level at roughly equal to ours about three or four years ago, before our inflation really started to hit the ouch stage. Good double hotel rooms with bath are still available for $20 or less, and food remains spectacularly cheap. You can get a steak dinner for about two dollars—and there’s no “plus tip” because New Zealand people rarely if ever tip. During our visit, a New Zealand friend took my wife to tea at the Midland Hotel, a charming, old-world sort of place on Lambton Quay in Wellington. They had four small sandwiches and four cakes apiece, and tea, and the tab totaled $1.25—for both!

One of the many other good reasons for visiting New Zealand is the opportunity to do some of the things you want to do after the season for

doing them has finished at home. This is the place for June, July and August skiing; for lying on a beach in January, February and March; and for trout and deep-sea fishing, deer hunting, tennis and golf all the year round. This is one of the few areas on earth where the deer hunter encounters no restrictions; he’s encouraged to shoot because the deer is officially rated a noxious animal in New Zealand, marked for extinction because it’s a nuisance to the farmers.

Not every traveler is a sportsman, though; most visitors are interested in meeting people, and this is the perfect place for it. New Zealanders are open, friendly, hospitable and relaxed—very possibly because the slow tempo of their lives and the relative freedom from pressure in their welfare state enable them to be that way.

The most interesting New Zealander I met on my recent trip was the Minister of Tourism and Associate Minister of Social Welfare, Mrs. Tini Whetu Marama Tirikatene-Sullivan, a forty-two-year-old, dark-eyed Maori beauty whose list of credits is far longer than her name, part of which is Maori for “clear white star.”

A contemporary, feminine version of the Renaissance man, the Honourable Mrs. Tirikatene-Sullivan is a former fashion model, New Zealand titleholder in ballroom and Latin American dancing, runner-up for the New Zealand women’s foils championship, and fencing instructor at New Zealand’s Victoria University and at the Australian National University. Her shorthand speed of 240 words a minute is, I understand, about ten words off the former world’s record ; she is a student pilot, designs her own clothes, and owns and operates a boutique featuring Maori designs in jewelry and fabrics. She and her husband, Dr. Denis J. Sullivan, an Australian nuclear physicist, have a three-year-old daughter.

She was a few months away from her Ph.D. at the Australian National University when she returned to New Zealand to run for one of the Maori seats in the New Zealand Parliament—the seat vacated by the death of her father. She was elected and then reelected by the largest popular vote ever given a New Zealand M.P., exceeding the previous record held by her father. Her two

grandmothers were Maori chieftainesses; one grandfather was the son of an English lord, the other was a Jewish immigrant from Central Europe.

“Generations of successful intermarriage have solved the racial problem for us here in New Zealand,” she told me. “About one out of every eight New Zealanders today has some Maori blood.”

An active conservationist, she believes tourism to be the least environmentally destructive means of gaining foreign exchange to help finance the Labour government’s plans for increased social services. “A pleasing environment is a basic tourist attraction,” she said, “and here in New Zealand our environment is unique in a world where pollution has become a part of life in a computerized society.”

Geography is the only thing that prevents New Zealand— "and especially its South Island—from becoming a major tourist destination. New Zealand is remote from the world’s population centers, and South Island is the more remote of the country’s twin islands. The South Island’s Southern Alps out-Alp the Alps of Switzerland, its lakes out-loch everything in Scotland except Lomond, its pastoral, rolling hill country and meadowlands are more pastoral and more extensive than England’s, its fjords around Milford Sound rival those of Norway and its trout fishing is rated the best on earth.

Much of New Zealand is sheep and cattle country—the Old West without the wildness. The Maoris were here first, like the American Indians; and like the Indians they fought hard for their land, and lost. But there the similarity stops. In New Zealand there are no Wounded Knees because the Europeans who settled there treated their defeated foes much more charitably and intelligently than did the Europeans who conquered the Indians. There are no Maori reservations, just a few villages devoted mainly to the preservation of the ancient culture. The Maoris have been completely integrated into the economic and political structure; there has been a great deal of intermarriage and relatively little social prejudice, and the status of the Maoris is comparable to that of their Polynesian racial brothers in Hawaii.

Whatever your age, you’ll become very youth conscious when you get to New Zealand. First, it’s a very youngcountry. European settlement didn’t begin until the early nineteenth century and the nation didn’t achieve

constitutional independence until after World War II. And you have to be careful how you walk here since flaxen-haired, blue-eyed rosycheeked kids or dark-skinned, blackeyed kids are forever running between your legs. They come in these varieties because more than ninety percent of the population are of British descent, many of the postwar immigrants have been Dutch, and most of the other New Zealanders are Maoris.

The profusion of children is due to the fact that, in contrast to the United States, large families are fashionable in New Zealand. Social legislation in this welfare state has made child rearing remarkably unpainful. Maternity services—prenatal, confinement and postnatal— are mainly free, public-hospital services are free and so is most medicine prescribed by doctors. General practitioners charge $3.75 to $4.35 U.S. for an office visit, and social service gives them a dollar or two more. Kids get free dental care, their education is free from kindergarten at age three or four through secondary school, and college fees are only about $75 a year. Doing their bit for the child culture, buses in the city of Christchurch are fitted with outside racks on which mothers can hang their baby buggies while they ride around town.

New Zealand is about the same size as Italy, but its population is only 2,862,000 compared to Italy’s 54,080,000; there’s plenty of room for everybody, so why shouldn’t the New Zealanders have as many kids as they care to? The spaciousness of the country will give most Americans a strong sense of nostalgia, and since we’re on such a strong nostalgia kick these days, nostalgia is a good reason for going there.

It’s farming country most of all, the kind of place your father or grandfather loved to tell you about— even if he was brought up in Pittsburgh. And the biggest cities are still small enough to be neighborly. In New Zealand a town becomes a city when its population passes 20,000. Auckland, the largest city, has a population of almost 700,000 and only four others—Wellington, Christchurch, Hamilton and Dunedin —have more than 100,000 each.

Auckland is very much the com/\ mercial metropolis of New ^ ^Zealand, Wellington is the capital; and there’s a fair amount of rivalry between these two North Island cities. Like Rio, Cape Town, San Francisco and other beautiful cities, Wellington is a seaport ringed by

(Continued on page 62)

(Continued from page 35)

mountains. Yet New Zealanders have a way of bad-mouthing their capital, if they don’t happen to come from there, as some Americans do Washington. The New Zealanders’ chief complaint about Wellington has to do with the winds that blow in from stormy Cook Strait that separates the North and South Islands. But the winds do keep the city smog-free and sparkling in the sun that seems to be shining most of the time. The climate couldn’t be better. Wellington is just about as far south of the equator as Saragossa, Spain, is north. Temperatures in midsummer, January, run from 55 to 68 degrees, and in the southern hemisphere’s midwinter they range from 42 to 51.

Christchurch, metropolis of South Island, is the southernmost major city on earth and the jump-off point for the U.S. Navy’s antarctic operation. Don’t get a picture, though, of dogsleds and igloos around Christchurch. Its southern latitude is comparable to Chicago’s northern latitude, but Christchurch’s weather is incomparably sweeter.

Nevertheless, too many tours and too many independent travelers— covering New Zealand, logically enough, as part of a swing through the South Pacific—spend a couple of days on the North Island, visiting Rotorua, Auckland and Wellington and the glowworms in the Waitomo Grotto (all interesting in their own way), and then push on to Australia, Fiji or wherever. By doing so, they miss the more scenically exciting of New Zealand’s two islands and also the one that better gives the visitor the feeling of a relaxed and untroubled way of life that, sadly, is becoming almost as uniquely New Zealand as the kiwi bird.

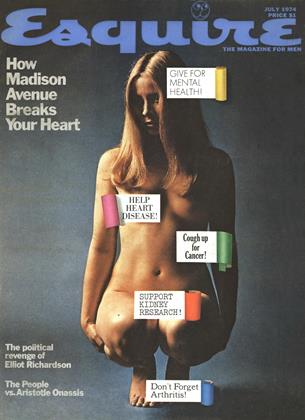

Get instant access to 85+ years of Esquire. Subscribe Now! Exclusive & Unlimited access to Esquire Classic - The Official Esquire Archive

- Every issue Esquire has ever published, since 1933

- Every timeless feature, profile, interview, novella - even the ads!

- 85+ Years of outstanding fiction from world-renowned authors

- More than 150,000 Images — beautiful High-Resolution photography, zoom into every page

- Unlimited Search and Browse

- Bookmark all your favorites into custom Collections

- Enjoy on Desktop, Tablet, and Mobile

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Articles

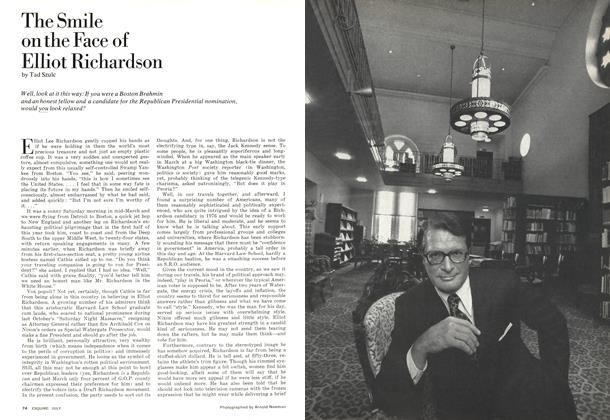

ArticlesThe Smile on the Face of Elliot Richardson

July 1974 By Tad Szulc -

Articles

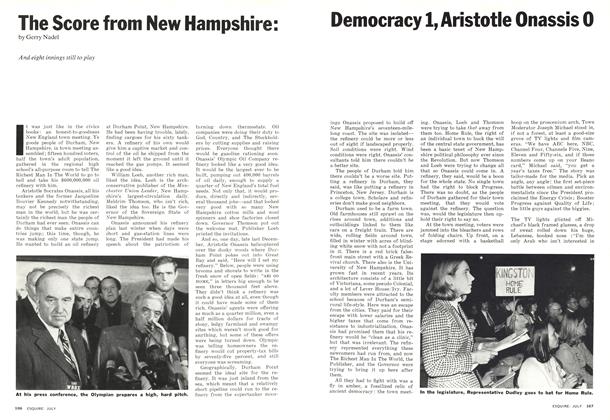

ArticlesThe Score From New Hampshire: Democracy 1, Aristotle Onassis 0

July 1974 By Gerry Nadel -

Articles

ArticlesFixing Things: A Guide for the Bewildered

July 1974 By Bill Elisburg -

Articles

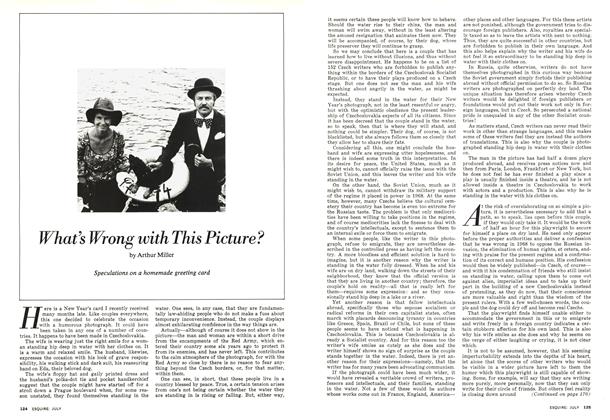

ArticlesWhat’s Wrong with This Picture?

July 1974 By Arthur Miller -

SUMMER SUPPLEMENT

SUMMER SUPPLEMENTOptional Excursion: A One-Way Ticket to New Zealand

July 1974 By Richard Joseph -

FICTION

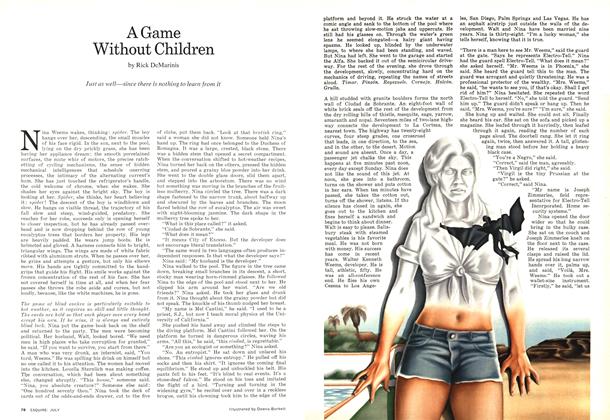

FICTIONA Game Without Children

July 1974 By Rick DeMarinis