The Highest Road to Scotland

For $2,900 a week, there’s a wonderful shooting vacation afore ye

Richard Joseph

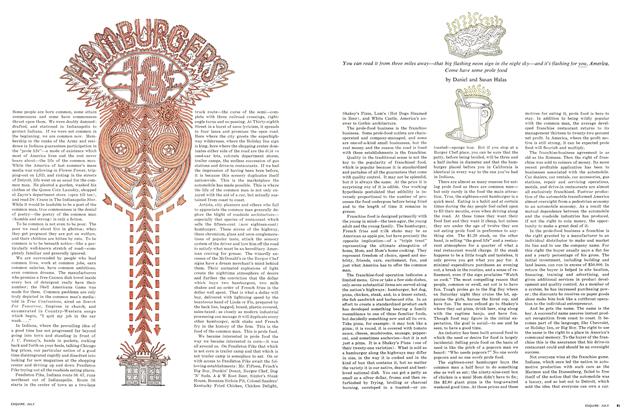

The Earl and Countess of Seafield would be delighted to have you and seven of your friends as their guests for a spot of grouse shooting on their ancestral Scottish estates next August and September. Well, perhaps guests isn’t precise, since acceptance of the invitation would cost you—at the current dollar exchange rate— just about $23,232 for five days of shooting. This could very possibly prove to be the most expensive vacation available on earth; however, if your friends were good sports enough to split expenses, the cost would come down to only about $580 per person for each day’s shooting.

The Seafields are most reluctant to accept reservations for parties of less than eight guns (in British sporting circles “guns” signifies shooters) because grouse shooting requires a certain amount of team sportsmanship, and you can’t have a bunch of blighters and bounders—all strangers to one another—blasting away with their double-barreled shotguns at the driven birds zooming by at seventy miles an hour or more at anywhere from.two to 150 feet above the moors.

What’s more, there’s a very social aspect to the scene. On arrival, one is unpacked by the butler, and one’s soiled linen is immediately carted below by the maid. One dresses in the proper tweeds with plus fours and perhaps leggings. One breakfasts on porridge and kippers. One lunches from hampers of squab and champagne. One dresses for dinner, of course—one’s dinner jacket has been laid out by the butler—and one has port or brandy with cigars in the lounge afterward.

It is a way of life that has all but disappeared from the British scene—even among the nobility, in accord-

ance with Gilbert and Sullivan’s warning. In Iolanthe, as I’m sure you will recall, they have the Fairy Queen threaten the peers with sessions of the House of Lords sitting throughout the grouse and salmon seasons. But economics is really what’s done it in—estate taxes, death duties and the enormous expense of maintaining the moors. At Seafield, a staff of six gamekeepers and two apprentices is kept busy the year round protecting the nesting birds in preparation for the five or six weeks of grouse shooting, depending on how long the stock of birds holds out.

Lord Seafield’s 150,000-*ere property encompassing parts of Banffshire, Inverness-shire and Morayshire in northeastern Scotland is more than ten times the size of Manhattan Island and is believed to be the largest private estate in Britain not owned by the royal family. A couple of years ago he decided to help defray expenses by creating the Seafield Sportings Club. (In Scotland, “sportings” is used in place of “sports”; thus, grouse, pheasant and duck shooting, salmon and trout fishing, and deer stalking—all offered splendidly at Seafield—are all different “sportings.”) But he did not go into trade—if indeed hotel-keeping constitutes going into trade nowadays—with the enthusiasm of some of his peers, most notably the Duke of Bedford at Woburn Abbey.

A certain ambivalence is easily discernible at Seafield. Guests are not put up in Cullen House—the turreted and crenellated grey stone castle that has been the ancestral home of the Seafields since the early sixteenth century—even though it could house an infantry regiment, but are lodged instead in Old Cullen— the twenty-five-room white stucco Georgian mansion that was the Earl’s home before he assumed the title— a couple of hundred yards away. “Positively Lucullan luxury” is the way the handsome Seafield brochure describes the scene. “The atmosphere is that of a very privileged country house party without the host dictating your programme.”

Not only doesn’t the host dictate the program, he’s not even there. This has caused a certain amount of confusion, since an earlier brochure, under the heading Questions you may wish to ask, contained the following colloquy :

“Will we meet the Earl and Countess?”

“Yes. They hope to have the pleasure of entertaining you to [sic] a cocktail party during your visit. However, as they are offering approximately thirty weeks’ sportings they are not able to guarantee that they will

always be available here owing to possible business commitments in other parts of the world.”

“What are they like?”

“They are young and charming and tend to prefer informality. The Earl is an outstanding shot and may well occasionally be able to come out with you on shooting days.”

This was all a mistake that was eliminated in the later brochure. We were told at Seafield, “The Earl and Countess lead active lives and they found greeting guests quite a strain.” An earlier visitor reported that an American woman guest at Old Cullen asked to be shown the castle’s public rooms and turned up wearing a full-length evening gown and a tiara in the hope that she would be presented to the Earl and Countess— which she wasn’t.

Seafield’s operation represents a strange amalgam of almost-reluctant commercialism and anachronistic snobbery. Mr. R.E.B. Yates, M.A.,

I F.R.I.C.S., who has the title of Factor and who runs the show for the Earl of Seafield, flew to New York a couple of years ago to make a pitch to a few top American tour operators and the travel press ; and the Sportings Club’s rate sheet states that “Old Cullen is ideal during the months of April to midAugust for top-level executive conferences, executiveincentive schemes and holidays. . . .” Yet when we arranged to visit Seafield, with the British Tourist Authority serving as intermediary, we were asked to maintain a low profile so as not to infringe on the privacy of other guests. Our early-May visit was at the very beginning of their season and the only other

guests were a Hamburg dentist and his wife and Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Rosenthal of Yardley, Pennsylvania, who did not object to the use of their names. We stayed at Old Cullen, but photographer John Marmaras, a personable and eminently presentable young Australian, was put up at a small but comfortable hotel owned by the Seafield Estates in the adjoining seaside village of Cullen.

The guest book at Old Cullen, though, shows that in season the Sportings Club is very definitely the province of German barons and French, Italian and Spanish counts, interspersed with continental industrialists and an occasional Texan or Californian. They are attracted by Seafield’s unique combination of superb shooting and fishing facilities and almost unseemly luxury.

Grouse shooting and salmon fishing are the top two sportings. The salmon season gets under way first, in late April, and lasts through September, with the best months May, June, July and September. The club has a beat along the River Spey, rated by fishing experts among the greatest salmon streams in the world. Reserved for Seafield guests, the beat may be fished by no more than seven rods at a time. The average season’s bag totals about 250 salmon, plus the magnificent sea trout and native brown trout that also inhabit the Spey. The salmon run up to forty pounds and the average is about ten pounds, although fifteento eighteen-pounders are quite common.

It’s about an hour’s drive from Old Cullen to the beat—riding through Seafield country all the way. Since there are only a few hours of darkness on Scottish summer nights, it’s possible to fish almost all night. Many Seafield guests do—eating and sleeping in the heated chalet that has been set up on the riverbank. There’s also fine lake fishing for rainbow and brown trout at two nearby lochs, where the fish run from one half pound to three pounds.

The salmon and grouse seasons overlap from about August 10 to September 20. There are two varieties of grouse shooting—walked or driven; the walked variety comes first, lasting about a week at the beginning of the season. In this version, you walk slowly across the moors in a sort of moving skirmish line, guns about forty yards apart, with keepers and dogs in between. The flushed-out birds rise suddenly, and somehow always unexpectedly, at your feet, and they in turn flush out coveys farther away, so there is a wide

variety of shooting angles and distances. Eight reasonably accurate guns should bag an average of fifty to a hundred brace of birds a day. Each gun is allowed to retain one brace a day ; the rest are kept by the estate and the keepers, and go to feed their families and friends.

The most challenging and exciting shooting, though, is for driven grouse, which goes on from mid-August until whenever the birds run out (about a month later). In this version you wait in butts or blinds dug into the rocky hillside while thirty to forty beaters and flankers, led by gamekeepers equipped with walkietalkies, move in from distant points, driving the birds toward you. You never know when a covey will suddenly explode over the brow of a hill right in front of you, flying low above the heather at high speeds. The trick is to get two birds out of each covey, one with each barrel of your shotgun. Really top shooters, though, have a loader with an extra shotgun standing by at their side in the butt, and when the birds appear they try for two grouse in front of the butt with the first gun, then hand the empty gun to the loader, grab the loaded one, pivot, and try for two more birds as they’re flying away to the rear. Guns who thus bag four grouse at a time are rewarded by applause and cries of “Well shot!” while the springer spaniels and Labradors scamper out from behind the butts to retrieve the fallen birds. The Seafield kennels, incidentally, breed an outstanding strain of English springer spaniel and sell trained hunting dogs for about $300 apiece.

Comes late October, and guests enjoy what Seafield people call the crème de la crème of their shootings— for driven capercailzie, a giant grouse weighing about twelve pounds and with enormous scaly claws that make it look like a prehistoric bird. The capercailzie travel at speeds up to eighty miles an hour on silent wings and they’re shot in the pine forests where they live. The caper is relatively rare ; shooters are satisfied if one bird is driven to their gun, three is very unusual. A sportsman who bags a caper cock usually has it stuffed and mounted.

So much for the birds. Deer shooting draws an entirely different sporting contingent to Seafield, although it can be combined here with salmon fishing and “top-level business meetings.” The deer come in two main varieties : the small and elegant roe deer and the larger red deer. The roebuck season lasts from late April until October 20, when the doe shooting begins and continues through February. During that time about three hundred bucks and does are shot on the Seafield lands for conservation and sport. Red-deer stalking for stags extends from mid-September until October 20, and for hinds it starts on October 27 and continues—with some interruptions—through January.

Seafield’s rates depend on when you go there, and what you’re going after. They’re set in Swiss francs— the management evidently wishing to have no part of the vacillating pound sterling these days—and for a six-day visit they range from a low of 2250 Swiss francs—for guests attending business meetings or for some other reason not wishing to take part in any of the sporting activities—to a high of 7200 Swiss francs for the prime grouse-shooting weeks, three in midAugust and the first two of September. These rates

do not include the ten percent value-added tax or another ten percent the management discreetly suggests as gratuities to the staff. With the Swiss franc currently at 2.94 to the dollar, that would make the cost of a six-day Seafield visit—including tax and tips— $2,904 for the grouse shooter and $918 for the nonactivist.

^■«p^he variety of Seafield’s sportings facilities is ' ■ " rivaled only by the elegance of its life-style, I now rare even in opulent homes, rarer in hotels and all but nonexistent in sporting lodges. JL. No more than seventeen guests can be accommodated in Old Cullen’s eight double-bedroom-withbathroom suites and one single bedroom. Central heating is controlled thermostatically by the temperature outside, but log fires burn in the lounge, library and dining room. You pour your own drinks in the bar, and in the dining room the butler and steward serve fresh and smoked salmon and trout, home-killed venison, mountain lamb, game birds and lobster, crab and prawns from the nearby sea—together with fine French white and red wines—on handsome china and glistening silver and crystal. Oil portraits of ancestral Ogilvies and Grants (Ulysses S. Grant descended from this clan) hang on the walls. A fleet of Peugeot estate cars, Land-Rovers and other vehicles stand by to take you to the shooting moors, the fishing beats, nearby golf courses, antique shops, Highland Gatherings and other local attractions, and to and from the airport at Aberdeen, fifty miles away. All is laid on handsomely, lavishly and tastefully, and everything is covered by the rates. All that’s missing at Seafield, in fact, are Seafields. -ttf

Get instant access to 85+ years of Esquire. Subscribe Now! Exclusive & Unlimited access to Esquire Classic - The Official Esquire Archive

- Every issue Esquire has ever published, since 1933

- Every timeless feature, profile, interview, novella - even the ads!

- 85+ Years of outstanding fiction from world-renowned authors

- More than 150,000 Images — beautiful High-Resolution photography, zoom into every page

- Unlimited Search and Browse

- Bookmark all your favorites into custom Collections

- Enjoy on Desktop, Tablet, and Mobile

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

ARTICLES

ARTICLESThe Outing

November 1974 By Ted Morgan -

PROFILES

PROFILESThe Passion of Mark Rothko

November 1974 By Lee Seldes -

ARTICLES

ARTICLESAll the World Wants the Jews Dead

November 1974 By Cynthia Ozick -

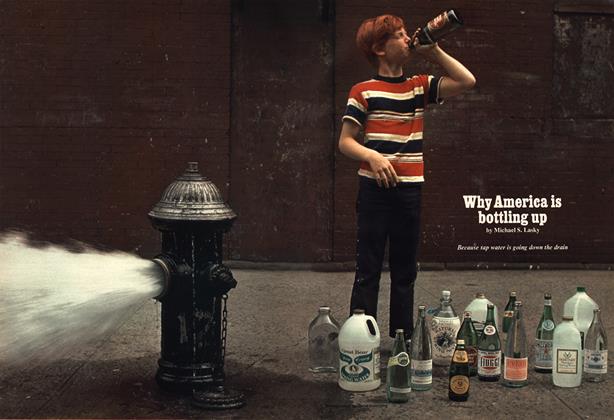

ARTICLES

ARTICLESWhy America Is Bottling Up

November 1974 By Michael S. Lasky -

FICTION

FICTIONThe Leaves, the Lion-Fish and the Bear

November 1974 By John Cheever -

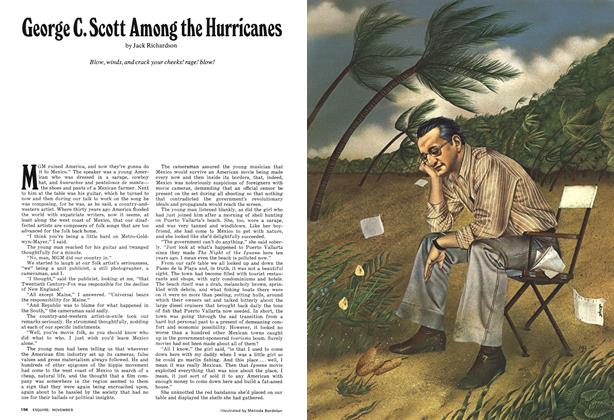

ARTICLES

ARTICLESGeorge C. Scott Among the Hurricanes

November 1974 By Jack Richardson