Market Forecast: '74-'75

ART AND MONEY

For the man who doesn’t know anything about investing, but knows what he likes

Fred Ferretti

Most of us are inexplicably ambivalent in the marketplace. We agonize as the price of a gallon of gas creeps upward a penny a day; we don’t like spending ten cents for a five-cent postcard, and a two-penny increase in the postal rates drives us up a wall. But ask us to pay a two-hundred-dollar increase on a combination rotisserie/ice crusher and we simply pay. I suppose that once something is designated a luxury it goes against our status-seeking grain to quibble over its price. What we’re saying to ourselves is: we’ve made it and we can pay. As it turns out, we’re often screwed. Nowhere is this more manifest than in the area of fine arts. How else to explain why we’ll walk into art galleries or any of those proliferating storefront graphics supermarkets or pipe-rack factory outlets and gladly put out $50, $100, $300 and more for worthless crap in fake Kulicke frames, for socalled pochoirs, for “museum-printed” and “museumquality” reproductions, for “stone-signed” and “platesigned” prints just torn out of picture books, for “signed” lithographs that are signed photos and for assembly-line paintings that are no more than decorative junk—and even “decorative” is debatable. We’ll trustingly spend our money simply on the say-so of the proprietors of these dens, who assure us—using the escalating costs of Rembrandts as illustration—of the innate and future value of their pieces, and most of the time—maybe all of the time—we’ll be taken.

So what is a mother to do ?

At that walk-in shopper’s level you’re better off, far better off, buying a book of classy reproductions. You’ll ultimately enjoy it more—for less.

But what of the “real” art market, the market of original classic and modern masters; of trendy and somewhat overpriced artists like John Chamberlain and Conrad Marca-Relli; of quality paintings, drawings and sculpture still within reach of you and me; of fresh, young legitimate artists and those older though still unrecognized; of inventors and experimenters with glass and steel like Guy Dill; of those who work with vinyl and plaster and foam; of Polaroids from the likes of Lucas Samaras ; of the environmental artists ; of master graphics from Picasso downward? Even at this level the con exists, though it is smoother. Bad Picassos are sold for prices identical to those of good Picassos because for some buyers Picasso is Picasso and enough said. Pencil-signed reproductions have been and are being bought by the thousands. Some artists with reputations even paint to order these days and, because of the constant desire for newness, more people are gimmicking up things and calling themselves artists, daring buyers not to regard

them as the quintessence of the avant-garde. Unscrupulous dealers pack auctions and with agreed-upon “competitive” bidding set artificially high prices for one school of art or another. Museums lend themselves to these market manipulations by showing one school, or one trend, over another, thus creating taste, and by permitting themselves to be influenced by p.r.-wise dealers.

The world of art, particularly in New York where more and more of the world’s standards and prices are set, is broadly a sellers’ market, as many people with varying amounts of bucks seek avidly to buy instant culture. However, for those with significant amounts of money to spend—say generally $500 to $1,500 for graphics, and from $5,000 to $10,000 for drawings, paintings and sculpture—it can become a buyers’ market, if one adheres to the following strictures: don’t gamble except with the best of advice, and even then be prepared to lose without whining; buy blue chip; buy one piece of the finest quality you can afford instead of a wall-filling flotilla of minor works; avoid mediocre works, even by major artists; buy expertise if you have to before you spend a dime.

Advice for a price—usually ranging from five to ten percent of the ultimate total purchase—can be had at most reputable galleries. The more prestigious houses cater to purchasers in the quarter-million-dollar class but a smaller gallery owner can be hired for the abovenoted percentages, or for a flat negotiated fee, to hold your hand while you buy. Don’t buy for investment, buy because you truly like a piece. If its value goes up, be satisfied with your prescience ; if it doesn’t, you still have your aesthetic pleasure. Remember that the art market anytime is just that, a market, and like all commodity-trading marts these days, it is fluid, hedgy and treacherous. Know at least how to tread water before you jump in over your head.

These cautions come from Dorothy Miller and are echoed by reputable dealers and gallery owners, who regard Miss Miller as the grande dame of the art-buying scene. For years she was associate curator of painting and sculpture at M.O.M.A., then curator of the museum’s collections—sort of super curator—under Alfred Barr, M.O.M.A.’s trend-setting director. In recent years she has advised institutions and individuals, including Nelson and David Rockefeller and David’s Chase Manhattan Art Program, and that transportation monolith, the Port of New York Authority, for whose World Trade Center she helped select the sculpture. “That Rothko that David has in his office I found for him, and that was when Rothko was under ten thousand dollars.” Nelson, she says, is a most responsive client. “He bought a great deal on our say-so and pledged it to the museum, as he promised.” And David “has a good eye. He learned fast. He knows his artists.”

It was Miss Miller who showed Mark Rothko in 1952 and Louise Nevelson in 1959—when everyone else was saying “Louise who?”—and who early on displayed the likes of Morris Graves and Hyman Bloom and the early work of the New York School contemporaries. “They used to say of my exhibits, there goes another bunch of Dorothy Miller’s Americans.” Well, Dorothy Miller’s Americans are very big business today and will continue to be, she believes. She also sees the trend toward the new “photographic realism” of such as Richard Estes continuing, and agrees with others that this fall will see somewhat of a boom among nineteenth-century American realists. Yet even though what she sees usually has gilded edges, she cautions against buying into trends simply for investment. “Only buy something you absolutely cannot do without,” she says. “I loathe buying for investment. I have never bought anything, either for myself or anyone else, that I haven’t absolutely loved.”

Tejas Englesmith of the glamorous Leo Castelli Gallery agrees. “It is after all a bit vulgar, this investment buying. We have people coming in asking us what we have in a certain price range and wanting virtual guarantees that their investment will double. It’s disgusting. I loathe it.” Yet galleries cannot ignore big money when it comes pouring through their doors. Says John Richardson of Knoedler, “Today the private collector is the exception. Our largest sales are to other dealers, mutual funds, Swiss banks, Japanese corporations. You don’t have great collections anymore, what you have are great bank-vault holdings.” Still, says Richardson, fine pieces of art are available in the $10,000 range, “But, for God’s sake, I would urge one to buy one fine piece, not a mélange.”

With the exception of continued sky-high blue-chip buying, the galleries believe this fall will be characterized by tight money. A buyer with significant cash to spend can be in the catbird seat. There are carryover trends from the spring and signposts indicating markets still inviting and cheap enough for the modest collector, but there seems little doubt that prices will continue to creep—read that leap—upward. This last season saw some enthusiastic buying of nineteenthcentury American and European paintings in both the London and New York auctions, and though the buying tended to be chauvinistic—Americans bought American and Europeans bought Dutch, Spanish and Italian—prices stayed reasonable. In the realm of contemporary art, in the $5,000 to $10,000 category, good art, very good art, is plentiful. One might for example hie himself and his advisor over to Wildenstein in New York where he could possibly pick up a small, tinyedition Henry Moore sculpture for around $6,000. Hell, if Moore is good enough for Joe Hirshhorn and M.O.M.A.’s Sculpture Garden it should be just smashing in your new rosewood hutch from Bloomingdale’s. And it could be profitable too, according to Harry Brooks, Wildenstein’s vice-president, who points out that small Moores have gone at auction recently for as much as $27,000. Don’t stand in line though, there just aren’t that many around.

Brooks is convinced that Paul Klee will be a hot artist this season, as will Lyonei Feininger—“I don’t handle them. I wish I did”—and he regards the surrealists—Magritte, Delvaux, Dali, Ernst, Brauner, Masson and Tanguy are some—as “hot stocks.” Richardson of Knoedler agrees that there has been “an enormous

boom in the surrealist painters and there are no indications I can see that they will slack off.” In particular he mentions Dali—“We’ve sold every painting of his we had last year. Amazing, the interest there”—and Tanguy, who has “gone up enormously in price.” Richardson also notes a “chauvinistic trend among American buyers. We are finding that Americans deliberately set out to buy Americans,” and thus such as Frank Stella, Larry Poons and Robert Motherwell have sold, and will continue to sell, he believes, very well.

Tejas Englesmith says much the same. Castelli, with the largest stable of in-the-news artists around, and fresh from the triumphs of last fall’s $2,200,000 Sotheby Parke Bernet sale of New York School works belonging to taxi baron Robert Scull—very many of which Castelli induced Scull to buy—sees the market in New York artists not only holding up, but growing in strength. An envious competitor adds that the Castelli stable “is selling by the ton in Europe too.” Paintings and sculpture by such as Johns, Kelly, Lichtenstein, Rauschenberg, Rosenquist, Warhol and Oldenburg are well into the thousands and most of us cannot afford them anymore, but careful shopping might turn up a drawing or a pencil or ink study for a finished work. And although their graphics too are “gradually getting out of sight,” according to Sylvan Cole Jr., director of Associated American Artists—the largest graphics outlet in the country, perhaps the world—they are still available.

A Kelly print can be had for about $600, Rauschenberg and Lichtenstein are somewhat higher, and Judy Harney, administrator of Pace Gallery, which handles through its Pace Editions the prints of such as Ernest Trova, Jack Youngerman and Nevelson, says that prints and multiples by these artists are still in the $300 to $1,000 bracket. Also hot now is Henry Moore, printmaker, who, says Cole, is “making more prints right now than at any time in his whole life,” and Wildenstein’s Brooks, a friend of Moore’s, says that the heavy demand for Moore prints is expected to increase so rapidly that his gallery, which has never had a print sale, will hold a November show of Moore graphics. Prices? Six hundred dollars to $1,600. Miro prints seem to be leveling off—although the level remains stratospheric—while Picassos and German expressionist prints continue to climb. Later Chagall prints, those awful purple and emerald green things that people seem to buy to match their new sofas, are incredibly expensive, but shopping around can get you a small, early black-and-white etching that will prove that Chagall was once really an artist.

U nderstand some basic art-world economics and then shop. A gallery works on a hundred percent markup, allowing a wide margin for negotia tions-and do bargain. In the case of paintings, drawings and sculpture-one-only originals-the price usually represents a simple one-step markup, but in the ever-burgeoning world of original graphics-etchings, woodcuts, engravings, lithographs-markups can grad uate like a flight of stairs. Original prints traditionally used to be conceived and produced by the artist, pains takingly, one at a time, and then a price was nego tiated with a gallery. This is seldom the case today. Printers and art publishers abound. Where ten years ago there were twenty or twenty-five important pub lishers of original works of art, today there are more than 500, and print experts say that is a conservative figure indicating "viable" publishers-not fly-by nighters who corral themselves one or two artists, produce editions and then sell-( and that 1000 might be a more realistic number. In France alone there are more than a hundred print publishers, perhaps as many as eighty in this country.

(Continued on page 196)

(Continued from page 130)

Printers and publishers are the new middlemen of art, and as their tribes increase, the cost of art to you and me rises accordingly. Example: An artist, a modest fellow, let’s say, produces a print that he believes he should receive $25 for. An edition of one hundred is agreed upon and he figures that $2,500 is not a bad rate of pay for his master plate. It is turned over to a printer, who receives $10 for each print he runs off. This brings the print price to $35 by the time the artist signs them and delivers them to the publisher. His markup of one hundred percent, plus $15 a print to his salesman, as an incentive, means that by the time it reaches the gallery it is at the $85 level. The gallery adds its markup and that print—to you—is now in the $150 to $175 range. And remember, the artist who created the print got $25. Kind of like the all-American radish farmer, no?

One way to avoid much of this added expense is to buy prints from outlets which you know deal with no middlemen. There are several, but the one most often recommended by the experts is Associated American Artists. Director Cole deals directly with artists, commissions editions and sells directly to the public. And what is A.A.A. selling these days? “Americans, a lot of them,” says Cole. “Now, more than ever, people are buying American prints.” He says his business in Benton, Avery, Davis, Kuhn, Davies and Marin increases steadily and “the indications to me are that it will stay constant this season.” Cole points out that among the better bargains available for buyers in the $4,000 class are prints by Edward Hopper. “I haven’t any, but they are around, and they’re a fantastically good buy at those prices.”

A valid index of what people bought in the spring and summer, and what they are buying now, is The Museum of Modern Art’s Art Lending Service. For $30 for two months you can have a signed print by Motherwell or Youngerman or Rosenquist hanging in your living room, and for about $180 you can dream grand things while looking at a Matisse. Of course you have to give them back at the end of the rental term, but you can buy anything you’ve rented and the rental charge will be deducted from the purchase price. And what have people been favoring? You guessed it. The New York School, at prices ranging from $200 to $1,000, with the average about $500. And the museum’s service seems to think it will be renting and selling more of the same this season.

So if you can’t buy, rent; and meditate upon your cash flow, as you try to figure out why Norton Simon is dumping his Impressionists and going into Far Eastern art. IB-

Get instant access to 85+ years of Esquire. Subscribe Now! Exclusive & Unlimited access to Esquire Classic - The Official Esquire Archive

- Every issue Esquire has ever published, since 1933

- Every timeless feature, profile, interview, novella - even the ads!

- 85+ Years of outstanding fiction from world-renowned authors

- More than 150,000 Images — beautiful High-Resolution photography, zoom into every page

- Unlimited Search and Browse

- Bookmark all your favorites into custom Collections

- Enjoy on Desktop, Tablet, and Mobile

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

ARTICLES

ARTICLESThe Outing

November 1974 By Ted Morgan -

PROFILES

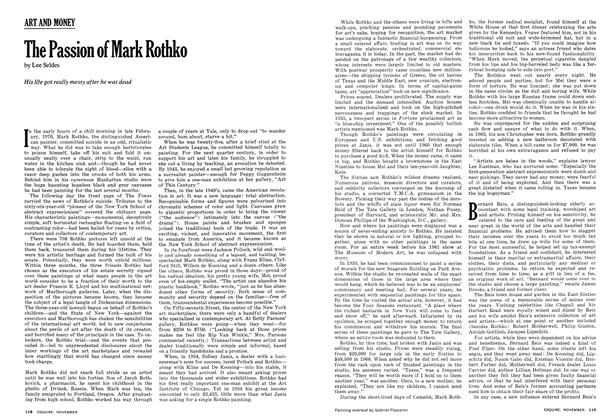

PROFILESThe Passion of Mark Rothko

November 1974 By Lee Seldes -

ARTICLES

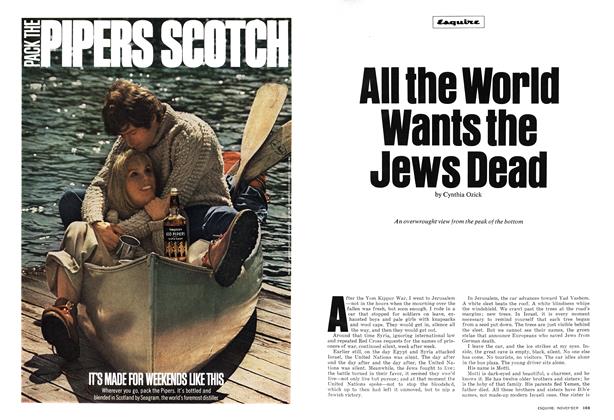

ARTICLESAll the World Wants the Jews Dead

November 1974 By Cynthia Ozick -

ARTICLES

ARTICLESWhy America Is Bottling Up

November 1974 By Michael S. Lasky -

FICTION

FICTIONThe Leaves, the Lion-Fish and the Bear

November 1974 By John Cheever -

ARTICLES

ARTICLESGeorge C. Scott Among the Hurricanes

November 1974 By Jack Richardson