BOOKS

MALCOLM MUGGERIDGE

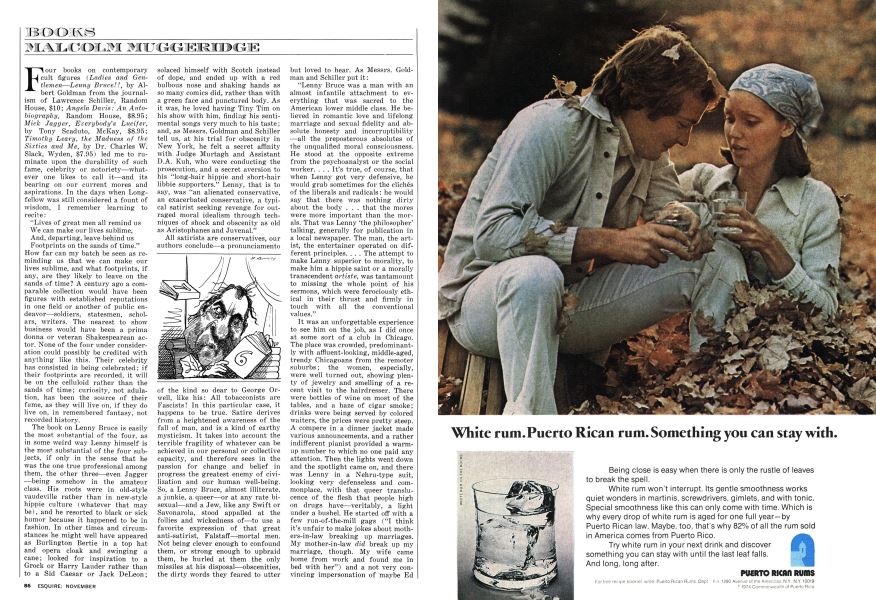

Four books on contemporary cult figures (Ladies and Gentlemen—Lenny Bruce!!, by Albert Goldman from the journalism of Lawrence Schiller, Random House, $10; Angela Davis: An Autobiography, Random House, $8.95; Mick Jagger, Everybody’s Lucifer, by Tony Scaduto, McKay, $8.95; Timothy Leary, the Madness of the Sixties and Me, by Dr. Charles W. Slack, Wyden, $7.95) led me to ruminate upon the durability of such fame, celebrity or notoriety—whatever one likes to call it—and its bearing on our current mores and aspirations. In the days when Longfellow was still considered a fount of wisdom, I remember learning to recite :

“Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time.” How far can my batch be seen as reminding us that we can make our lives sublime, and what footprints, if any, are they likely to leave on the sands of time? A century ago a comparable collection would have been figures with established reputations in one field or another of public endeavor—soldiers, statesmen, scholars, writers. The nearest to show business would have been a prima donna or veteran Shakespearean actor. None of the four under consideration could possibly be credited with anything like this. Their celebrity has consisted in being celebrated; if their footprints are recorded, it will be on the celluloid rather than the sands of time; curiosity, not adulation, has been the source of their fame, as they will live on, if they do live on, in remembered fantasy, not recorded history.

The book on Lenny Bruce is easily the most substantial of the four, as in some weird way Lenny himself is the most substantial of the four subjects, if only in the sense that he was the one true professional among them, the other three—even Jagger —being somehow in the amateur class. His roots were in old-style vaudeville rather than in new-style hippie culture (whatever that may be), and he resorted to black or sick humor because it happened to be in fashion. In other times and circumstances he might well have appeared as Burlington Bertie in a top hat and opera cloak and swinging a cane; looked for inspiration to a Grock or Harry Lauder rather than to a Sid Caesar or Jack DeLeon;

solaced himself with Scotch instead of dope, and ended up with a red bulbous nose and shaking hands as so many comics did, rather than with a green face and punctured body. As it was, he loved having Tiny Tim on his show with him, finding his sentimental songs very much to his taste ; and, as Messrs. Goldman and Schiller tell us, at his trial for obscenity in New York, he felt a secret affinity with Judge Murtagh and Assistant D.A. Kuh, who were conducting the prosecution, and a secret aversion to his “long-hair hippie and short-hair libbie supporters.” Lenny, that is to say, was “an alienated conservative, an exacerbated conservative, a typical satirist seeking revenge for outraged moral idealism through techniques of shock and obscenity as old as Aristophanes and Juvenal.”

All satirists are conservatives, our authors conclude—a pronunciamento

of the kind so dear to George Orwell, like his: All tobacconists are Fascists! In this particular case, it happens to be true. Satire derives from a heightened awareness of the fall of man, and is a kind of earthy mysticism. It takes into account the terrible fragility of whatever can be achieved in our personal or collective capacity, and therefore sees in the passion for change and belief in progress the greatest enemy of civilization and our human well-being. So, a Lenny Bruce, almost illiterate, a junkie, a queer—or at any rate bisexual—and a Jew, like any Swift or Savonarola, stood appalled at the follies and wickedness of—to use a favorite expression of that great anti-satirist, Falstaff—mortal men. Not being clever enough to confound them, or strong enough to upbraid them, he hurled at them the only missiles at his disposal—obscenities, the dirty words they feared to utter

but loved to hear. As Messrs. Goldman and Schiller put it :

“Lenny Bruce was a man with an almost infantile attachment to everything that was sacred to the American lower middle class. He believed in romantic love and lifelong marriage and sexual fidelity and absolute honesty and incorruptibility ■—all the preposterous absolutes of the unqualified moral consciousness. He stood at the opposite extreme from the psychoanalyst or the social worker. . . . It’s true, of course, that when Lenny got very defensive, he would grab sometimes for the clichés of the liberals and radicals : he would say that there was nothing dirty about the body . . . that the mores were more important than the morals. That was Lenny ‘the philosopher’ talking, generally for publication in a local newspaper. The man, the artist, the entertainer operated on different principles. . . . The attempt to make Lenny superior to morality, to make him a hippie saint or a morally transcendent artiste, was tantamount to missing the whole point of his sermons, which were ferociously ethical in their thrust and firmly in touch with all the conventional values.”

It was an unforgettable experience to see him on the job, as I did once at some sort of a club in Chicago. The place was crowded, predominantly with affluent-looking, middle-aged, trendy Chicagoans from the remoter suburbs; the women, especially, were well turned out, showing plenty of jewelry and smelling of a recent visit to the hairdresser. There were bottles of wine on most of the tables, and a haze of cigar smoke; drinks were being served by colored waiters, the prices were pretty steep. A compere in a dinner jacket made various announcements, and a rather indifferent pianist provided a warmup number to which no one paid any attention. Then the lights went down and the spotlight came on, and there was Lenny in a Nehru-type suit, looking very defenseless and commonplace, with that queer translucence of the flesh that people high on drugs have—veritably, a light under a bushel. He started off with a few run-of-the-mill gags (“I think it’s unfair to make jokes about mothers-in-law breaking up marriages. My mother-in-law did break up my marriage, though. My wife came home from work and found me in bed with her”) and a not very convincing impersonation of maybe Ed Sullivan or Billy Graham. The only response was a few titters; they weren’t going to accept this pap, they wanted the hard stuff. I noticed one or two of the ladies near where I was sitting moving irritably in their places. Okay, Lenny seemed to decide, they must have it, and he began, working up to a crescendo of filth, insults, self-pity; the ravings, as it seemed to me, of impotent flesh, a sick mind and a lost soul. How they loved it ! What roars of laughter and applause! One might have been actually watching D.H. Lawrence write Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

After their perceptive account of what made Lenny tick, it is disappointing to find Messrs. Goldman and Schiller taking so seriously his squalid way of life; his essays in group sex, and everlasting indulgence in pill-dropping, with, of course, a hypodermic always within reach. All the same, they are to be congratulated on never for one moment suggesting—which must have been a temptation—that he was a victim of the Establishment, or the militaryindustrial complex, or the fuzz. As far as the last was concerned, on the contrary he was prepared on occasion to act as a police informer. Also, I agree with their conclusion: “Once Lenny committed himself to the jazz life, to the jazz myth, he was destined to the end that awaits all such comet-like figures flashing across the American night. He had never withheld himself from his fate. Never sought to deflect his destiny. He knew he was doomed as well as he knew his name.” By the time he was forty, his act and his health had collapsed, his money had run out, and he had become obsessed with points of law culled from his own experiences in the courts, and with a book about spiritualism called The Road to Immortality—one of those accounts of conversations with disembodied spirits recorded with the utmost solemnity in the early years of this century. So there was nolhing left for him to do but take an overdose and die, which he duly did.

No one can accuse Angela Davis of leaving us in any doubt as to who is responsible for her and her fellow Afro-Americans suffering the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. She makes it abundantly clear that our old friends the Establishment, the military-industrial complex, and —very much to the fore—the fuzz are to blame. From the beginning she found herself among the downtrodden and oppressed—though somehow she went to Brandeis. Every policeman she encounters is a brute, every black-power adherent a suffering saint. America is fascist, imperialist and racist; its law is farcical, its courts are a travesty. Only in Castro’s Cuba and in Brezhnev’s U.S.S.R. is the pure air of freedom to be breathed. So it goes on. Unfortunately, this makes her narrative as predictable as one of those Victorian novels in which you know beyond a peradventure that the wicked squire will try to seduce the virtuous maidservant, but that somehow her virtue will triumph. A pity, because I should have been interested to know the mental and emotional processes whereby an obviously well-educated, above averagely intelligent and attractive girl like Miss Davis came to throw in her lot with so violent and obscurantist a movement as black power, and to swallow so narrow and bigoted a party line as the orthodox Communist one. Also, how far her own mixed blood made for difficulties in identifying herself with Afro-Americans. Alas, I found her autobiography as unconvincing as Soviet election returns, and after several tries abandoned it as unreadable.

When last heard of (as far as I was concerned), Dr. Timothy Leary had arrived in Switzerland after an inhospitable reception in Algeria and an unproductive encounter there with Eldridge Cleaver. Now, thanks to an erstwhile friend, Dr. Charles W. Slack, we have an account of how Dr. Leary fared in the land of the yodel. A photograph on the dust jacket of Dr. Slack’s book shows him as curly-haired and open-eyed, rather like a surprised faun, not in the first flush of youth, but still quite sprightly. He is, it appears, a clinical psychologist who teaches at the University of Alabama Medical Center in Birmingham. His wife, Eileen, who accompanied him on his visit to Dr. Leary, is superintendent of the State Training School for Girls. When she told Dr. Leary that her job was to look after young girls who became pregnant, he looked disconcerted, though whether at the notion of young girls becoming pregnant, or at their needing or receiving care, is not clear. To Dr. Slack, Dr. Leary seemed altogether a shadow of his former self ; all the bounce gone out of him, no longer the ebullient prophet of joy through LSD, short of money. The company round him was tatty, he was under an expulsion order from Switzerland, which he had so far ignored but which might at any moment be enforced. Perhaps due to Eileen’s influence, the magic of Dr. Leary’s message no longer worked on Dr. Slack, and he formed the impression, rightly or wrongly, that his old friend had become a mere junkie.

Now Dr. Leary is back in California serving a fifteen-year sentence for escape and possession, and Dr. Slack and Eileen are living happily in a cottage on the grounds of the Alabama State Training School for Girls. What the moral of this story is, if any, I have no idea.

Then Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones; for my generation a pulsating heap of flesh, octopus-like, seen on a screen to the accompaniment of weird cries. Tony Scaduto has done his best to provide an account of the human side of this phenomenon, describing his places of residence, associates, loves and work techniques. He includes what is, to me, an imperishable scene, when, after a police-court appearance on a drugs charge, Jagger has a secret rendezvous in a remote field for a TV interview with four questioners, all concerned having been carried there in helicopters. The four questioners are: an Anglican bishop, the editor of The Times, an eminent Jesuit father and a former home secretary who is now a peer of the realm. In other words, the Establishment in person. A piece of social history, surely.

Just when I was wrestling with these intimations of twentiethcentury lunacy I was particularly grateful to receive from the widow of Reinhold Niebuhr a little volume she has collected of his sermons, meditations and prayers (Justice and Mercy, edited by Ursula M. Niebuhr, Harper & Row, $5.95). It was comforting to realize that this man of outstanding wisdom, piety and integrity had also been perplexed by our contemporary scene. Indeed, at one point, he almost got involved in the absurdity of appearing as a witness for Lenny Bruce, but very honorably withdrew in time. I was the more moved that he, too, should feel impelled to pray: “Let your light so shine in our darkness that our perplexity may not lead us to despair. As perplexity humbles our pride, may we see more clearly what you would have us do” ; while he concludes his last address by quoting from the Pensées, where Pascal writes of how “philosophers can tell me about man’s dignity, and they drive me to pride, or about man’s misery, and they drive me to despair. Where, but in the simplicity of the gospel will I know about both the dignity and the misery of man?” Niebuhr adds: “These words were spoken in the seventeenth century. They are relevant to our task today.” Everyone fortunate enough to possess Mrs. Niebuhr’s collection will want to keep it by the bedside, -ttf

Get instant access to 85+ years of Esquire. Subscribe Now! Exclusive & Unlimited access to Esquire Classic - The Official Esquire Archive

- Every issue Esquire has ever published, since 1933

- Every timeless feature, profile, interview, novella - even the ads!

- 85+ Years of outstanding fiction from world-renowned authors

- More than 150,000 Images — beautiful High-Resolution photography, zoom into every page

- Unlimited Search and Browse

- Bookmark all your favorites into custom Collections

- Enjoy on Desktop, Tablet, and Mobile

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

ARTICLES

ARTICLESThe Outing

November 1974 By Ted Morgan -

PROFILES

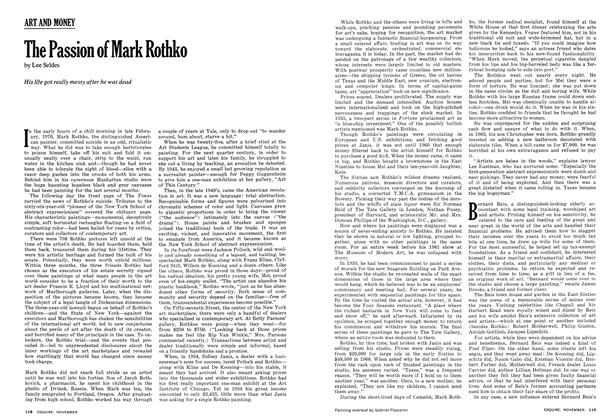

PROFILESThe Passion of Mark Rothko

November 1974 By Lee Seldes -

ARTICLES

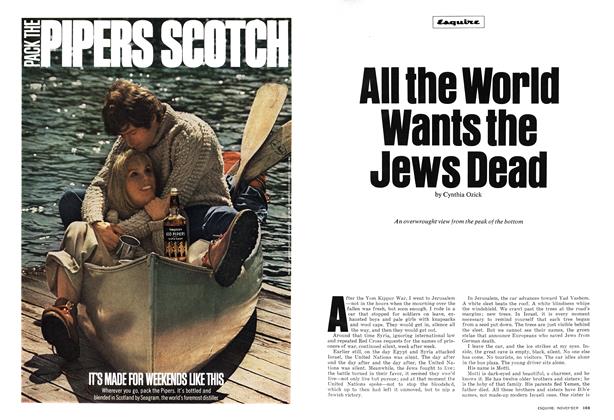

ARTICLESAll the World Wants the Jews Dead

November 1974 By Cynthia Ozick -

ARTICLES

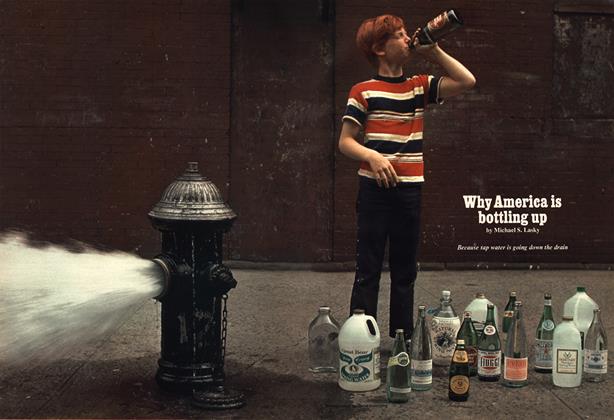

ARTICLESWhy America Is Bottling Up

November 1974 By Michael S. Lasky -

FICTION

FICTIONThe Leaves, the Lion-Fish and the Bear

November 1974 By John Cheever -

ARTICLES

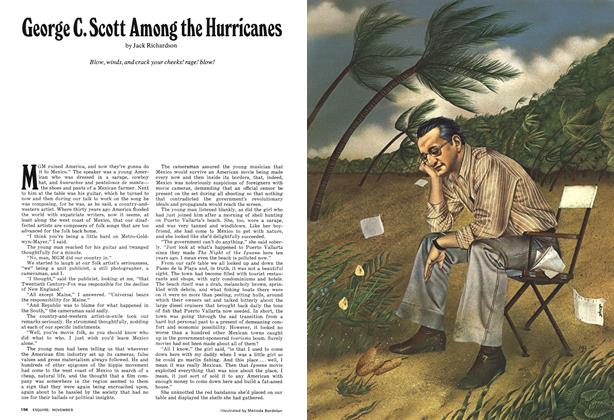

ARTICLESGeorge C. Scott Among the Hurricanes

November 1974 By Jack Richardson