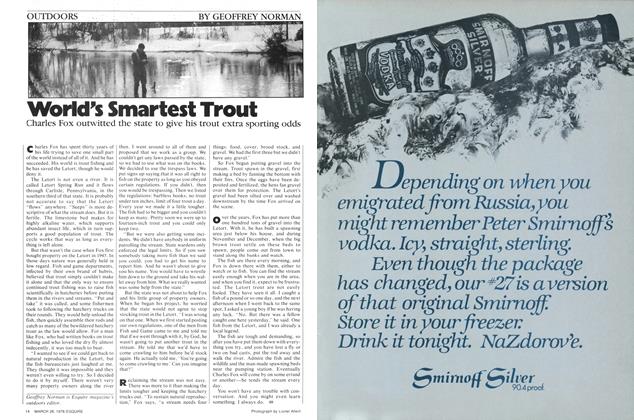

OUTDOORS

THOMAS WILIAMS

Early in the summer my daughter, who is eight, came running up toward the cabin saying that a little boy was lost down in the woods by the brook, and was calling for his mother. Peter, who is ten, was still down there trying to find him. We heard the noise too, a piercing blat I thought must be an animal of some kind—a rabbit’s death scream, a deer’s blat, or even some sort of birdcall. It wasn’t too different from the scream of a young crow or an excited blue jay. My wife went down, but I stayed for a moment because I was talking to a hiker who had just come down from the mountain.

It might have been a lost child — we’ve had them here before. The Appalachian Mountain Club lodge is little over a half mile away from us, and at one place down in our valley we’ve let them clear a trail through some long-abandoned apple orchards. When the hiker left I put a .22 pistol in my pocket and started down the trail to the brook, feeling that my wife would by then have identified whatever was yelling. But at that moment came other evidence—of what exciting or tragic thing I didn’t know. Peter began calling, “Dad! Dad!”, in a voice I heard from far away, made ragged by wind and leaves, that could have been either his usual impatience at my not appearing immediately, or real panic.

I yelled, “What? What?”, knowing that he was on the other side of the brook and couldn’t hear me over the water sounds. As I waited, my impatience born of sudden fear, I heard Ann and my wife calling for me too, and I began to run. I left the trail in order to take a shorter way through the woods, breathlessly jumping over rocks and branches, ducking most limbs and being whipped by others. It’s strange how one’s anxiety, even in such violent motion, is full of pictures and alternatives. I saw the moonlike face of a child who’d hit his head on a rock and drowned in the brook—just the pale head of the child, swollen as though slightly hydrocephalic. Or perhaps a rabid fox had bitten Peter, and I saw hyperdermic needles and the bad statistics of that long process of cure. Also I was prepared to be terribly angry, sick and breathless if it were nothing at all, and they had misled me into fear. And as I ran toward some possible horror, the sight of my child or another child in pain, or whatever it would be, I felt, too, some small wonder at my direction. Shouldn’t I have been running the other way? But I charged down through the woods, into the alders in the valley, crossed the brook on rocks and yelled for Pete. I seemed to be carrying a huge cloud of noise along with me, and as I stopped to listen I had the feeling one has after an explosion.

Then my wife and children appeared beside the brook, all healthy and perversely calm, it seemed to me.

“What is it? What’s the matter? What’s the matter?” I said.

“It’s in there,” my wife said. My vision was just clearing—clearing of anger and panic, I suppose, and I looked through the dense alders. Something brown and fairly large was thrashing around in there— something about the size of a dog. I went in cautiously, and suddenly it rose. It was a spotted fawn. It ran a step or two and crashed into the weeds and fallen alder limbs. I thought immediately of the doe, and waited for a moment. The fawn was obviously hurt. It tried to run, and again it fell awkwardly forward onto its neck. Its fur was all wet and ragged. Without thinking at all I ran to it and stood over it.

What was I supposed to do with it? There was the fawn’s face, and its huge dark eyes, open and alive. Its stripes and spots moved as it tried to get its legs under it again. I leaned down toward it, and all at once I had it in my arms, the soft hair and the feel of quivering tendons. I thought, How could this wild deer be alive and in my power? All that truly wild energy which, especially in the deer, is so superhuman, even magic, I held against my awkward body. I’ve seen deer run with only shreds of heart left—run right out of sight. I’ve shot deer, but in most seasons I’ve merely heard them crash away, or caught a glimpse of grey or a flash of a white tail before they were gone. They always seem to know me, to have known all about me long before my dull senses are ever aware of them.

Then the fawn screamed, and I dropped it. There had been no warning from that calm face. This close, the terrified blat was so intense I’m not sure I can describe it. Perhaps the scream of an hysterical soprano —one whose arm is being pulled off. It seemed to have a direct effect upon my motor responses, and I never did get used to it. I still wonder if this cry had any effect as protection— say from the wildcat the children had evidently scared away. I’m sure even a hungry wildcat would be fairly disconcerted by such a sound.

I gathered the fawn in my arms again and brought it back across the brook, and we climbed back to the cabin. Our little beagle, who’d been off somewhere, had followed our trail and caught up with us. He wasn’t particularly interested in the deer, which makes me believe it had little scent—his world strikes him most forcefully through the nose. But just to keep the fawn a little calmer, Peter tied him up on the other side of the cabin, and we settled down on the grass to see how badly the fawn was hurt.

It had bled quite a bit on my shirt, and we found a definite set of teeth marks in the shoulder, and other cuts on the neck that looked like claw holes. Since the marks of attack were around the neck and shoulders, we assumed it had been a cat—a dog or coydog would have been after its hamstrings and flanks. The left front hoof was partly paralyzed, and wouldn’t stay straight; it was this, probably because of a pinched or cut nerve, that kept the fawn from running. Suddenly it blatted again, and I was so startled I instinctively let it go. One step and it was down on its neck again.

My wife found an old plastic baby bottle and a nipple, and we tried to get it to eat. I held it and Peter or Ann would shove the nipple into its mouth. It seemed strangely passive about this—no change from that calm deer expression at all. But when it squeezed a drop of milk from the nipple and tasted it, it seemed terribly offended, and the explosive blat disorganized us all. The bottle landed three feet away. This happened several times, and each time the fawn blatted, it would struggle madly to get away. In between it didn’t struggle at all. The dark eyes were calm and wide open, and the only expression came when its black nose retracted and large wrinkles appeared on its face as it sniffed us. I can imagine how we smelled to it— like Ores to a Hobbit, perhaps.

Of course the children didn’t think so. In their minds we had rescued this sweet fawn from a wildcat, a sinister monster totally unlike us. And I suppose this is what I’m getting after, here, because we can’t help yearning for this sort of innocence.

The pathetic fallacies of Walt Disney do not seem especially incongruous to children—even to mine, who feed frogs to garter snakes. (There is the frog, thinking, thinking, as the snake gums him around in his mouth so he’ll go down head first, alive. The snake’s bright eyes are open, and so are the frog’s. And so are the children’s, who bend interestedly over Pete’s terrarium.) And this little fawn, as its fur dried out and arranged itself, was more beautiful than any cartoon of Bambi could ever hope to be. It breathed, and stared at us, and smelled its mortal enemies all around it.

“It’s so cute!” Ann said. “It’s so pretty!”

“Can we keep it?” Peter asked.

We did keep it, for three days, because Bill Mooney, the game warden, was off scuba diving for a drowned fisherman—whom he found, by the way. We kept the fawn in the guest room, with a bundle of foliage and a bowl of water. It didn’t seem interested in the foliage, but continually spilled the water. At night we’d hear it clumping around up there, and when we looked in at it in the daytime it was curled in a corner, silent, immobile, with only the wrinkled nose expressing anything other than watchfulness.

Its wounds began to fester, and we worried about that, but Bill Mooney came one night with his daughter, who cuddled the little animal in her arms as they drove off.

“A ward of the State,” Bill called the little fawn.

Then, about a month later, we had another sort of confrontation with the wild population that sneaks through our woods, knowing us for what we are. One afternoon we heard two shots, and later a pickup truck came down the road and out again. A day later a visitor found guts across the valley, and mentioned this to us.

Bill Mooney came again—this time on his day off—and we all went to look at the scene of the crime. Other agents had been busy. The liver and heart had dried to a leathery sheen, but the stomach and intestines flashed white with thousands of maggots, who lived and rose with furious energy, bright as moonlight glinting on little waves. Downwind the effluence was so great we were amazed at its invisibility—that heavy air should have dimmed out the sun.

We came around upwind. Pete and Ann said nothing, but stood side by side and stared intently at the busy pile.

“It doesn’t look like a deer,” I said. The guts seemed bigger, darker, with more of murder about them. I couldn’t explain why.

“That’s what I was thinking,” Bill said. “Notice they didn’t take the heart and liver.” He smiled, and seemed to take real, but rather grim enjoyment from the *foib'les of the men who broke his laws. He is a big man, and his green uniform and badge made him seem even bigger. His holster and black ammunition pouches seem shinier and bulkier than anyone else’s, and I can’t imagine him—the man, and the officer of the law he is so proud to be-—ever turning aside from any task. I mention this because at that moment I was glad indeed that he had no reason to be after me.

He found a short stick, straddled the guts and poked a hole in a loop of intestine. A soft hiss, and he stopped breathing and stared intently at the trees above him for a long time. Then he looked down and poked at the intestine again. A dark collection of small objects, some wrinkled as raisins, some shiny and yellow and varnished, moved at the end of his stick; they were all held together as in a pudding by the congealed chemicals of digestion.

‘Berries. Insects,” Bill said through his teeth, and he moved carefully and quickly upwind.

Then we knew that it had been a bear. We found where it had been dragged a short distance, and on this trail we found two or three silky

black hairs.

“There’s where it crossed the trail,” Bill said.

He was still savoring the antics of his criminals. “Target of opportunity,” he said. “Target of opportunity.” We looked for the expended shells, but couldn’t find them, and then we all went back across the valley to the cabin. We did describe the pickup truck, which was a rather odd one. Perhaps Bill has caught whoever did it by now. I don’t know.

It was then I realized how glad my wife and children were that it had been a black bear, not a deer.

“It was a bear,” Ann said to Peter.

“It was a bear,” he said. “A big black "bear.”

They were relieved, and I wondered if they had been thinking of the bereaved mother of our little fawn. And yet to me the bear’s death seemed darker and more ominous. I remember reading about a man who couldn’t skin out a bear, because a bear naked of his skin looks too much like a naked man, a corpse. But violence and disorder are the way in our woods, and of course I’ll be there in the proper season, too, an agent of it.

Before Bill left he told us that the fawn had recovered completely and had been released to the woods again. Ours? I wondered. Our woods? In November I’d be out here with my rifle, looking as fiercely as anyone for a target of opportunity, and if I scored we’d all have plenty of rare venison, which we love to eat. I suppose, after all, we do not really refute Bambi, but we are complicated, manifold, dark, and we can digest more than the incongruous—enjoy, in fact, our sentimentality along with our meat. +H-

Get instant access to 85+ years of Esquire. Subscribe Now! Exclusive & Unlimited access to Esquire Classic - The Official Esquire Archive

- Every issue Esquire has ever published, since 1933

- Every timeless feature, profile, interview, novella - even the ads!

- 85+ Years of outstanding fiction from world-renowned authors

- More than 150,000 Images — beautiful High-Resolution photography, zoom into every page

- Unlimited Search and Browse

- Bookmark all your favorites into custom Collections

- Enjoy on Desktop, Tablet, and Mobile

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Articles

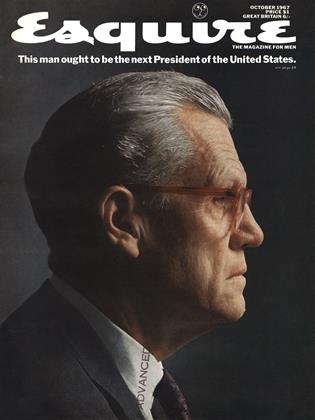

ArticlesIs It Too Late for a Man of Honesty, High Purpose and Intelligence to Be Elected President of the United States in 1968?

October 1967 By Steven V. Roberts -

Articles

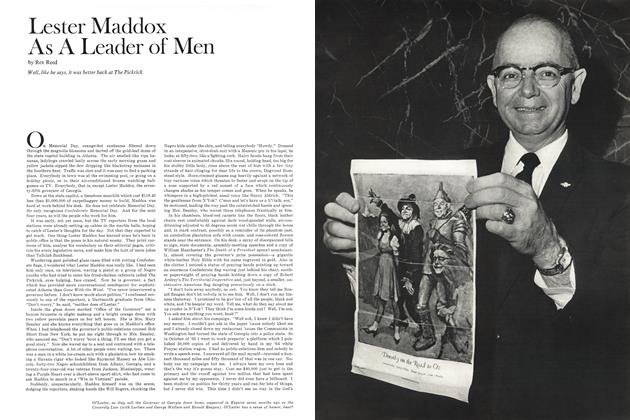

ArticlesLester Maddox as a Leader of Men

October 1967 By Rex Reed -

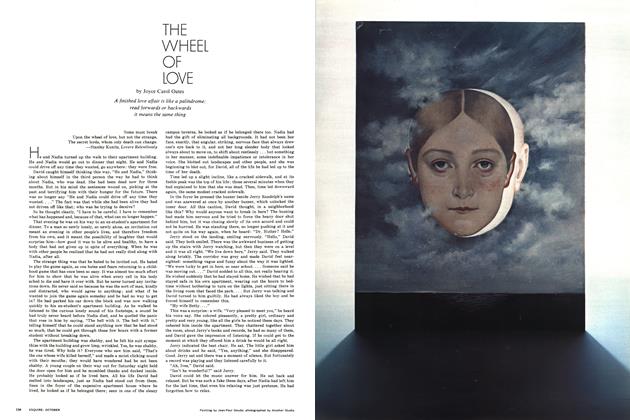

Fiction

FictionThe Wheel of Love

October 1967 By Joyce Carol Oates -

Articles

Articles100 Yards and 60 Minutes of Black Power

October 1967 By George Frazier IV -

Articles

Articles47 Places in America to Buy Land and Make Money

October 1967 By William H. Robbins -

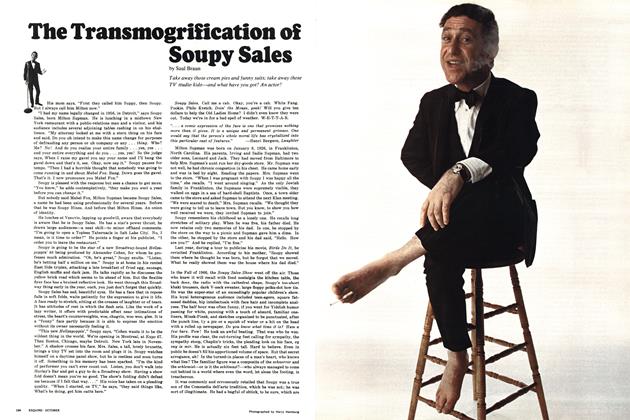

PROFILES

PROFILESThe Transmogrification of Soupy Sales

October 1967 By Saul Braun